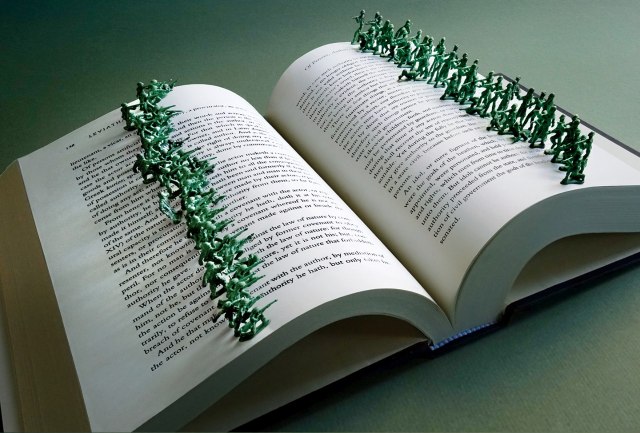

LINES ARE DRAWN A battle over pricing may have been the Sarajevo moment. But the war is really about the future of publishing—and maybe of culture.

I never tire of “think pieces” on Amazon because it is about our cultural future:

The War of the Words

Amazon’s war with publishing giant Hachette over e-book pricing has earned it a black eye in the media, with the likes of Philip Roth, James Patterson, and Stephen Colbert demanding that the online mega-store stand down. How did Amazon—which was once seen as the book industry’s savior—end up as Literary Enemy Number One? And how much of this fight is even about money? Keith Gessen reports.

By Keith Gessen Photo Illustrations by Stephen Doyle

I. DiscoveryOtis Chandler is a tall, serious, bespectacled man in his mid-30s whose grandfather, also named Otis Chandler, used to own the Los Angeles Times. Chandler grew up in Los Angeles, attended boarding school near Pomona, and then, like his father and grandfather, went to Stanford. Upon graduation he entered the computer field. Because it was the turn of the millennium, that meant working at a start-up: Chandler found a job at Tickle.com, which was an early venture in social networking. At Tickle, Chandler eventually became a project manager, starting a dating site called LoveHappens.com. It did O.K. In 2004, Tickle was acquired by Monster Worldwide, parent company of Monster.com, the huge job-posting site, and about a year and a half later, Chandler left.He started to think about what he should do with himself. One day, while visiting a bookish friend, he had what he calls an epiphany. “He had one of those bookshelves in his apartment,” Chandler told me when I met him in San Francisco. “You know what I mean, the bookshelf when you walk into someone’s house, the one where they keep all their favorite books. I walked into his living room and started checking out his shelf and just grilling him, like, ‘That looks cool. What’d you think of it? What’d you think of ’ ” He left his friend’s place with 10 good books. “I was like, if I could go to all my friends’ living rooms and grill them about what books they like, I would never lack for a good book again. But instead of doing that, why don’t I just build a site where everybody puts their shelves in their profiles?”He started to think about what he should do with himself. One day, while visiting a bookish friend, he had what he calls an epiphany. “He had one of those bookshelves in his apartment,” Chandler told me when I met him in San Francisco. “You know what I mean, the bookshelf when you walk into someone’s house, the one where they keep all their favorite books. I walked into his living room and started checking out his shelf and just grilling him, like, ‘That looks cool. What’d you think of it? What’d you think of that?’ ” He left his friend’s place with 10 good books. “I was like, if I could go to all my friends’ living rooms and grill them about what books they like, I would never lack for a good book again. But instead of doing that, why don’t I just build a site where everybody puts their shelves in their profiles?”

BY BILLY FARRELL/PATRICKMCMULLAN.COM. PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY STEPHEN DOYLE. Michael Pietsch, former Little, Brown publisher and now C.E.O. of Hachette.

Chandler started building an online platform that would allow users to link to and rate the books they’d read and also to add books that they wanted to read. He thought about calling it Bookster (“that was when -sterswere hot,” he said), but by the time it launched, one year later, the site was called Goodreads. It quickly gained a reputation. By the end of the first year, 2007, it had 650,000 registered users. At the end of five years, it had close to 20 million.

The site was popular among readers, and it soon caught on with publishers also, Chandler recalled, because it addressed a looming dilemma: “What ended up happening was that discovery was becoming the biggest problem in publishing.”

This was true. The term came into widespread use around 2010, when, after 40 years in business, the major book chain Borders began its final decline. What was the value of these bookstores to publishers? It wasn’t just that they sold the merchandise and split the money. It was that they displayed the merchandise. And if bookstores were going out of business, as they were, and if readers were moving online, as they were, then how could publishers show off their wares? Chandler remembers being deeply impressed by a publishing executive’s telling him, in 2006, that the way to make a best-seller was to put a copy of the book on the front table of every bookstore in the country. But there was no front table online. Serendipitous browsing would need to be replaced by vastly superior recommendation engines. Goodreads did well by simply connecting people with their friends and also with readers who had similar interests, allowing them to share lists and ratings and reviews. In 2011 the company took things to the next level by buying Discovereads.com, a recommendation-engine outfit. The new technology allowed Goodreads to start recommending books based on a huge variety of relevant factors.

BY T. J. KIRKPATRICK/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES. PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY STEPHEN DOYLE.Jeff Bezos, founder and C.E.O. of Amazon. As negotiations became deadlocked, Amazon began delaying Hachette books and erecting a form of blockade against the publisher.

Goodreads gave publishers some hope that they could solve discovery; it may also have given them hope that they could solve a more immediate problem: Amazon. By the time Borders went bankrupt, in 2011, and closed all its stores, Amazon was selling more print books than anyone; was selling more e-books than anyone; was beginning to have success with unknown authors publishing directly in the electronic format; and, most important of all, was the go-to site for book-buying research and recommendations. Amazon was the publishers’ biggest customer but also, increasingly, a competitor, and also, increasingly, too good a customer. Publishers were becoming aware that they were overly reliant on Amazon. In 2011, several publishers announced a joint venture called Bookish, which was going to be a recommendation engine-slash-online bookstore, maybe even an Amazon competitor. But the Web site was a flop. Publishers weren’t very good at creating tech start-ups, but luckily Goodreads had already done it. Maybe the digital future wouldn’t be quite as scary as all that.

Then, in March 2013, for an undisclosed sum, Goodreads was bought by Amazon.

II. Battlespace

This past year has seen hostilities between Amazon and the publishers, which had been simmering for years, come out into the open, filling many column inches in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, not to mention numerous online forums. The focal point of the dispute has been a tough negotiation between Amazon and the publisher Hachette, with some public sniping between the companies’ executives (who have otherwise kept out of view). Hachette, it should be said, is no slouch: it is owned by the large French media conglomerate Lagardère. The other big publishers are similarly well backed. HarperCollins is owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. Simon & Schuster is a part of CBS. Macmillan and Penguin Random House are owned, or co-owned, by hefty German corporations. Nonetheless, all the publishers feel bullied by Amazon, and Amazon, in turn, feels misunderstood.

It wasn’t always this way. When Amazon first appeared, in the mid-90s, mailing books out of the Seattle garage of its founder, Jeff Bezos, it was greeted with enthusiasm. The company seemed like a useful counterweight to the big bookstore chains that had come to dominate the book-retailing landscape. In the late 1990s, the large chains, led by Borders and Barnes & Noble, controlled about a quarter of the adult-book market. Their stores were good. They may have lacked individuality, but they made up for it in inventory—a typical Barnes & Noble superstore carried 150,000 titles, making it as alluring, in its way, as the biggest and most famous independent bookstores in America, like Tattered Cover, in Denver, or City Lights, in San Francisco. Now a person on a desolate highway in upstate New York could access all those books, too.

The big chains were good for publishers because they sold so many books, but they were bad for publishers because they used their market power to dictate tough terms and also because they sometimes returned a lot of stock. People also worried about the power of the chains to determine whether a book did well or badly. Barnes & Noble’s lone literary-fiction buyer, Sessalee Hensley, could make (or break) a book with a large order (or a disappointingly small one). If you talked to a publisher in the early 2000s, chances are they would complain to you about the tyranny of Sessalee. No one used her last name; the most influential woman in the book trade did not need one.

The success of Amazon changed all that. It has been said that Amazon got into the book business accidentally—that it might as well have been selling widgets. This isn’t quite right. Books were ideal as an early e-commerce product precisely because when people wanted particular books they knew already what they were getting into. The vast variety of books also allowed an enterprising online retailer to leverage the fact that there was no physical store in a single fixed location to limit its inventory. If a big Barnes & Noble had 150,000 books in stock, Amazon had a million! And if Barnes & Noble had taken its books to lonely highways where previously there had been no bookstores, Amazon was taking books to places where there weren’t even highways. As long as you had a credit card, and the postal service could reach you, you suddenly had the world’s largest bookstore at your fingertips…

Pingback: A Book To Gift | Raxa Collective

Pingback: Resistance, Change, Art, Words–Liberating | Raxa Collective

Pingback: Be Wary, Is The Point | Raxa Collective