A Tamarind Tree’s Sweet and Sour Inheritance

My ancestor was gifted a huge orchard just outside Delhi. The fruits it produced were the taste of my childhood.

Gifts from ancestors take the darndest forms. Mine included a tamarind tree, the tallest and most magnificent in our yard. My grandfather’s grandfather—a tall, corpulent Indian, prone to indulging in fine wines, fine poetry, and fine art—lived in Delhi and worked for the British. This was 1857, a time when Indians were gearing up to fight the British. The conflict that ensued would later be called India’s First War of Independence. The British would call it the Indian Mutiny. Continue reading

India

10,000 New Electric Buses In India

Seven years and many bus stories among us recall the old buses. Noisy, smoke-belching, hot and crowded. Time to retire the old ones and at least lessen the noise and belching. Thanks to Sarah Spengeman and Yale Climate Connections:

India makes a big bet on electric buses

Fast-growing cities need electric buses if the country is to meet its climate goals.

Public transportation riders in Pune, India, love the city’s new electric buses so much they will actually skip an older diesel bus that arrives earlier to wait for a smoother, cooler ride in a new model. This has fed a new problem: overcrowding. Fortunately, more new buses are on the way. Continue reading

Frogs, Western Ghats & Science

Sathyabhama Das Biju (from left), James Hanken, Harvard’s Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology, and Sonali Garg during a June 2023 field trip to study amphibians in the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot in India. Photo by A.J. Joji

During our seven years living and working in the Western Ghats we came to appreciate frogs through the eyes of our family, those of our staff, as well as travelers and occasional scientific references (the man on the left in the photo to the left having shown up in our pages one of those times). Good to know that the science is being shared for good cause, thanks to Anne J. Manning in this article for the Harvard Gazette:

Indian herpetologists bring their life’s work to Harvard just as study shows a world increasingly hostile to the fate of amphibians

Having pulled themselves from the water 360 million years ago, amphibians are our ancient forebears, the first vertebrates to inhabit land.

After 136 years from its original description, Günther’s shrub frog was recently rediscovered in the wild. Credit: S.D. Biju and Sonali Garg

Now, this diverse group of animals faces existential threats from climate change, habitat destruction, and disease. Two Harvard-affiliated scientists from India are drawing on decades of study — and an enduring love for the natural world — to sound a call to action to protect amphibians, and in particular, frogs.

Sathyabhama Das Biju, the Hrdy Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute and a professor at the University of Delhi, and his former student Sonali Garg, now a biodiversity postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, are co-authors of a sobering new study in Nature, featured on the journal’s print cover, that assesses the global status of amphibians. It is a follow-up to a 2004 study about amphibian declines.

Biju and Garg are experts in frog biology who specialize in the discovery and description of new species. Through laborious fieldwork, they have documented more than 100 new frog species across India, Sri Lanka, and other parts of the subcontinent.

According to the Nature study, which evaluated more than 8,000 amphibian species worldwide, two out of every five amphibians are now threatened with extinction. Climate change is one of the main drivers. Continue reading

Stories from the Field: Birding with Clement Francis

Stories from the Field: Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Year 2015 was special for Shashank Dalvi. It was his “Big Year” – a birder’s personal challenge to identify as many species as possible within that time period. I had the opportunity to bird with him and learn from him earlier in the year. He is truly devoted to nature and fills up your brain with tonnes of useful and jaw-dropping information on all creatures in the wild. He decided to wrap the year finding the Nicobar Megapod and was travelling to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. He managed to obtain permission with several Government departments for himself and our group of 8 birders to travel to Central and Great Nicobars before closing the year in Gujarat.

We were to leave for Port Blair on 15th December, and the timing couldn’t have been worse. Chennai and the east coast of India was drowned in rains. Ominous clouds moved in fast-forward mode. It was like watching a horror movie.

Nature’s fury rendered people and their deities helpless. Bridges and dams tumbled down. People were stranded in higher floors. More than 15 feet of water covered the low-lying residential areas. The expedition was 5 days away.

I googled the weather pattern over Andamans and Nicobars. I could not see a bit of land. Just purple swirls. The first ever trip with legal documents to travel to any of the islands of Central and Great Nicobar might get washed out due to rains. Continue reading

India’s Progress With Solar Power Generation

Progress on solar power generation in India is a big deal. The country’s reduction in poverty, remarkable as it has been, is counterbalanced by its environmental impoverishment. Thanks to Reuters for this article by Sarita Chaganti Singh and Sudarshan Varadhan:

Exclusive: India amends power policy draft to halt new coal-fired capacity

NEW DELHI/SINGAPORE, May 4 (Reuters) – India plans to stop building new coal-fired power plants, apart from those already in the pipeline, by removing a key clause from the final draft of its National Electricity Policy (NEP), in a major boost to fight climate change, sources said. Continue reading

The Future Of Solar In India

A local farmer grazes his goats along a road overlooking Pavagada Solar Park. Photographs by Supranav Dash for The New Yorker

Difficult to imagine that with all the times India has appeared in these pages, and separately all the times that solar has appeared, this is the first time they appear together:

India’s Quest to Build the World’s Largest Solar Farms

Pavagada Ultra Mega Solar Park, a clean-power plant the size of Manhattan, could be a model for the world—or a cautionary tale.

Ashok Narayanappa drives a bullock cart carrying hay, along a stretch of road lined with pylons, in Pavagada Solar Park.

Every morning in the Tumakuru District of Karnataka, a state in southern India, the sun tips over the horizon and lights up the green-and-brown hills of the Eastern Ghats. Its rays fall across the grasslands that surround them and the occasional sleepy village; the sky changes color from sherbet-orange to powdery blue. Eventually, the sunlight reaches a sea of glass and silicon known as Pavagada Ultra Mega Solar Park. Here, within millions of photovoltaic panels, lined up in rows and columns like an army at attention, electrons vibrate with energy. The panels cover thirteen thousand acres, or about twenty square miles—only slightly smaller than the area of Manhattan. Continue reading

Dam Damage Done

A couple of our earliest posts was about life around a dam in India, so the photo heading this article rings a bell of sorts:

As Projects Decline, the Era of Building Big Dams Draws to a Close

Escalating construction costs, the rise of solar and wind power, and mounting public opposition have led to a precipitous decrease in massive new hydropower projects. Experts say the world has hit “peak dams,” which conservationists hail as good news for riverine ecosystems.

The end of the big dam era is approaching. Continue reading

All That Breathes, A Film & A Feeling

With a film review titled It’s easy to focus on what’s bad — ‘All That Breathes’ celebrates the good it would be difficult to resist reading, but spoilers can be annoying; not here:

With a film review titled It’s easy to focus on what’s bad — ‘All That Breathes’ celebrates the good it would be difficult to resist reading, but spoilers can be annoying; not here:

In Anne Lamott’s book on writing, she tells a great story about facing tasks that seem overwhelming. Her 10-year-old brother was doing a big school project on birds, and as the deadline loomed, he became paralyzed by how much he still had to do. His father put his arm around him and gave him a piece of advice, “Bird by bird, buddy,” he told him. “Just take it bird by bird.”

This useful life lesson takes literal form in All That Breathes, a wonderful new documentary that arrives on HBO and HBO Max garlanded with international awards. Directed by Shaunak Sen — and ravishingly shot by Ben Bernhard — this inspiring film takes us inside the lives of two ordinary seeming Muslim brothers in Delhi who are actually extraordinary in their dedication to doing good in a city teetering on the edge of apocalypse.

The brothers are named Saud and Nadeem, the former friendly, the latter a little grumpy. Continue reading

Stories from the Field: The Great Rann of Kutch, Gujurat

6 months after the Kaziranga trip, I started reading about the birds of India. I was very surprised to learn that we had more than 1,200 species across the country. I ventured out a bit, driving around Bannerghatta National Park and Hesarghatta Lake. Photographing birds isn’t as easy as one would think. They are flighty and fickle. I captured several images of “bird-less” perches and returned home with “bird-less” memory cards as well.

I was 56 years old and time was not on my side. I began to list out important birding areas in the country. This way, I could focus on numbers- my goal being to reach 500 birds before my health deteriorated. I chose birding locations that were easily accessible by car. Gujarat and Uttarakhand had large bird counts and winters were ideal for birding.

I decided to travel to the Great Rann of Kutch during November 2012. I didn’t want any delay seeing and photographing birds. I needed the right gear and I purchased a Canon 1D mark14 with a 500 mm f4 lens. A friend of mine drove me to Kutch, making it an easier trip for me. We chose a Homestay run by a famous conservationist and bird guide, Sri. Jugal Tiwari. All the rooms were named for beautiful local birds, which was very inspiring. I chose the Grey Hypocolius room just because the name sounded exotic. Most special was the fact that each room had books by the bedside,

mine had two about the world-famous birder, Phoebe Snetsinger.

Stories from the Field: Kaziranga National Park, Assam

Stories from the Field: Namdapha National Park, Arunachal Pradesh

I now realize that when I posted about my experience at Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary, I had gotten ahead of myself, because the germ of that visit began at Namdapha National Park. Namdapha…the name flirts and rolls around to fill your mouth, just as trekking there fills your senses.

I first met with Shashank Dalvi in March 2015 when he had organised a trek to Namdapha. After my initial foray into Kutch, I traveled every month of the year and covered the Central Himalayas extensively. I badly wanted to photograph the colourful birds of the North East and grow my list to 1000 birds of India. I had covered most parts of India by the time I was ready to travel to Namdapha.

I was seeking solitude and needed to take life at an easy pace during 2015. All the travel around the rest of India was done at a frenetic pace. Namdapha was that perfect place to bird at a gentle pace and that solitude came from the serene and silent forest. A perfect place to be lost inside a forest that totally separates you from rest of the world.

I had heard from every corner about Shashank Dalvi and especially about his work in Doyang, Nagaland. He and his team had put a stop to the annual culling of Amur Falcon’s in Nagaland, especially in Doyang.

We had heard rumors of large-scale bird hunting around the Doyang Reservoir in Nagaland some time ago. In September 2012, Bano Haralu, Ramki Sreenivasan, Rokohebi Kuotsu and I decided to investigate. What we saw shocked us – a massacre of thousands of Amur Falcons. Roko and I spent the next couple of days filming the slaughter and interacting with the hunters to understand the extent and nature of the hunt. It remains the most difficult and emotionally harrowing experience of my career.

Since then, I always wanted to bird alongside this man and learn his skill and patience. When you are in love with all creatures around you and understand their roles and impact on universal relationships you become patient in your role towards contributing toward their conservation.

I became a bit more patient. 7 days in Namdapha and surroundings gave ample time to listen about snakes, and behaviour of many mammals.

listen about snakes, and behaviour of many mammals.

Namdapha is declared a Project Tiger Reserve. It is also known as the land of four big cats. The only place on earth to host them all in one forest. This is also the place for rare mammal like the Takin, Musk Deer and the veryrare Slow Loris. The fragrant Agarwood is also found here. With an area of 2000 square kilometers, Namdapha is the largest virgin forests of India. Continue reading

India’s Zero Sum Game

When Pradip Krishen began creating Jaipur’s Kishan Bagh Desert Park, it was a wasteland of dunes and bald hillocks, strewn with trash. Looking at the landscape, he said, “Now, this is something I’d love to work on. ”Photographs by Bharat Sikka for The New Yorker

If I had to bet, based on our period living in India from 2010 to 2017, I would bet on the prime minister winning. That implies the country making less progress on conservation, if any, and more on development. As Dorothy Wickenden‘s article implies, it may be a zero sum game:

The Promise and the Politics of Rewilding India

Ecologists are trying to undo environmental damage in rain forests, deserts, and cities. Can their efforts succeed even as Narendra Modi pushes for rapid development?

Krishen’s first major restoration job was reclaiming the landscape around Mehrangarh Fort, in the Thar Desert.

On May 12, 1459, the Rajput warrior ruler Rao Jodha laid the first foundation stone of an impregnable fort, atop a jagged cliff of volcanic rock in the Thar Desert of Marwar. He called the citadel Mehrangarh, or “fort of the sun”—and, legend has it, he insured a propitious future by ordering a man buried alive on its grounds. Over time, as the royal clan secured its power, the compound grew to colossal proportions, with soaring battlements, ornately furnished palaces, and grand courtyards enclosed by intricate sandstone latticework. Four hundred feet below, the capital city of Jodhpur became a flourishing trade center. Continue reading

Unexpectedly Amazing In Kerala

In our Kerala days we visited Wayanad many times, but I would remember if I had met Shaji. We would have sought his advice to expand on the agricultural initiatives at the properties we developed and managed. Monika Mondal’s story ‘The tuber man of Kerala’ on a quest to champion India’s rare and indigenous crops brings back memories of unassuming neighbors doing unexpectedly amazing things:

Shaji NM has devoted his life to collecting and farming tubers such as yam, cassava and taro, and promoting them across the country

Shaji NM has spent the past two decades travelling across India to collect rare indigenous tubers. Photograph: Shaji NM

Known as “the tuber man of Kerala”, Shaji NM has travelled throughout India over the past two decades, sometimes inspecting bushes in tribal villages, at other times studying the ground of forests closer to home among the green hills of Wayanad in Kerala. His one purpose, and what earned him his title, is to collect rare indigenous varieties of tuber crops.

“People call me crazy, but it’s for the love of tubers that I do what I do,” says Shaji. “I have developed an emotional relationship with the tuber. When we did not have anything to eat, we had tubers.” Continue reading

When Fences Are Un-Neighborly

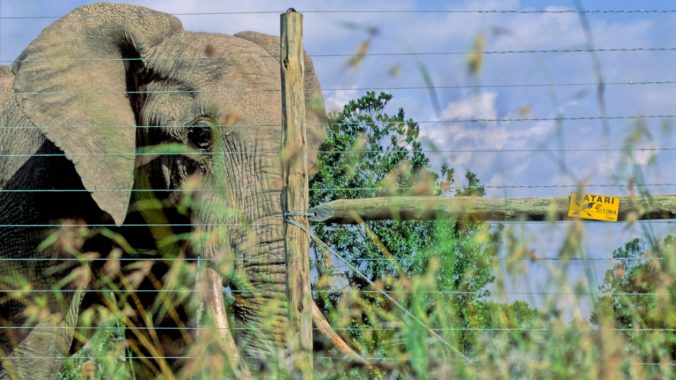

Volunteers modify a wire fence in Wyoming to allow wildlife to pass through. ABSAROKA FENCE INITIATIVE

If we take Robert Frost’s poetic license into the realm of how humans and wildlife might coexist more successfully, then the image above is powerful. Good fences might make good neighbors if they allow wildlife to migrate as needed.

While working in the Patagonia region of Chile, 2008-2010, I saw images like this in the photo to the right regularly. On occasion the sight would be more gruesome. Ranchers had erected fences without regard for the need of guanacos to wander.

During our seven years living in India the human-elephant relationship was often one of worshipful respect, but included too many stories of fences, or worse, as methods farmers used to protect their properties from elephant intrusions. As is the case in Kenya (see the image below) fences are unneighborly. So, we were on the lookout for creative solutions. The following article by Jim Robbins, in Yale e360, is timely and welcome in this regard.

An African elephant alongside an electric fence in Laikipia, Kenya. AVALON / UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Unnatural Barriers: How the Boom in Fences Is Harming Wildlife

From the U.S. West to Mongolia, fences are going up rapidly as border barriers and livestock farming increase. Now, a growing number of studies are showing the impact of these fences, from impeding wildlife migrations to increasing the genetic isolation of threatened species.

The most famous fence in the United States is Continue reading

Organic Cotton, India & Veracity

Harvested organic cotton at a bioRe facility in Kasrawad, India. India is the single largest producer of the world’s organic cotton, responsible for half of the supply. Saumya Khandelwal for The New York Times

When I see a headline like That Organic Cotton T-Shirt May Not Be as Organic as You Think my first reaction is a reflexive wince.

I will read the article for sure, as I did in this case, but even before reading it I feel defensive.

I am deeply committed to organic certification and seven years living in India makes this subheading into a red flag in terms of my sharing it with others:

The organic cotton movement in India appears to be booming, but much of this growth is fake, say those who source, process and grow the cotton.

Not because it is hard to believe. Exactly the opposite. I had work experiences that this story echoed in a different context. But when I share articles I value each day, usually on an environmental topic, a large percentage of those who click and read are from India. That is likely because we started this platform 10+ years ago while based in India. I do not enjoy, even if I am confident of its veracity, sharing news that I know will make those visitors, not to mention my many friends in India, uncomfortable.

Farmers set up their load of cotton at the Khargone mandi, a large auction market. Saumya Khandelwal for The New York Times

But I got over it. Each of the journalists who authored this story put something on the line to get these important facts about two topics I care about. So, please read on and visit the source so the authors and photographer are properly credited for their excellent work:

Michael Kors retails its organic cotton and recycled polyester women’s zip-up hoodies for $25 more than its conventional cotton hoodies. Urban Outfitters sells organic sweatpants that are priced $46 more than an equivalent pair of conventional cotton sweatpants. And Tommy Hilfiger’s men’s organic cotton slim-fit T-shirt is $3 more than its conventional counterpart. Continue reading

Hargila

“Hargila” Film Documents India’s Grassroots Effort to Save the Endangered Greater Adjutant Stork

A new film by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Center for Conservation Media tells the story of a wildlife photographer who travels to India intent on documenting the rarest stork on earth, but soon discovers a conservation hero and her inspiring efforts to rally a community to save it. Hargila documents the Greater Adjutant, a huge scavenging stork that was once widely distributed across India and Southeast Asia but is now mostly confined to a last stronghold in Assam, with small populations persisting in Cambodia’s northern plains region. Greater Adjutants are called “hargila” in the Assamese language, which literally translates as “bone swallower.” Continue reading

Tamil Nadu, Rice, Identity

In the early days of our posting here south Indian rice was a staple in our meals, and we knew that this now global foodstuff had a long history in other cultures. But it looks like the state neighboring where we lived may have found a clue to how much longer they have had rice in their diet:

An ancient rice bowl complicates the story of civilisation in India

In Tamil Nadu, archaeology is part of a contest over history and identity

Rarely can a spoonful of rice have caused such a stir. When M.K. Stalin, chief minister of Tamil Nadu, addressed the south Indian state’s legislature on September 9th, he celebrated a musty sample of the country’s humble staple. Carbon dating by an American laboratory, he said, had just proved that the rice, found in a small clay offering bowl—itself tucked inside a burial urn outside the village of Sivakalai, near the southernmost tip of India—was some 3,200 years old. This made it the earliest evidence yet found of civilisation in Tamil Nadu. The top duty of his government, the chief minister triumphantly declared, was to establish that the history of India “begins from the landscape of the Tamils”. Continue reading

Giant Storks Of Assam, And Their Protectors

If you saw some of the work that came out of Seth’s bird-focused interactions with children in Ecuador, and in Costa Rica, this might not seem so surprising. But in every case when kids are enlisted to help ensure care of bird populations, the result is noteworthy. And of course, when a community of women decide something is important, watch and learn. Carla Rhodes, a wildlife conservation photographer, shares this remarkable story from Assam:

A Biologist, an Outlandish Stork and the Army of Women Trying to Save It

In the Indian state of Assam, a group of women known as the Hargila Army is spearheading a conservation effort to rescue the endangered greater adjutant stork.

Life can change in an instant, as I experienced when I first laid my eyes on a tall and bizarrely striking bird known as the greater adjutant.

It was India in 2018, in the northeastern state of Assam. I’d ended up there partly because of absurd circumstances, which involved being filmed for a reality television pilot while navigating a motorized rickshaw through the Himalayas. Continue reading

Pygmy Hogs In Assam

A highlight of seven years living and working in India was a brief visit to Assam to review the land holdings of an investor who was considering having us assist with the development of a conservation-focused lodge. I did not know about this endangered species at the time, but its current status brings a good vibe to my day for more than one reason:

Pig in clover: how the world’s smallest wild hog was saved from extinction

The greyish brown pygmy hog (Porcula salvania), with its sparse hair and a streamlined body that is about the size of a cat’s, is the smallest wild pig in the world, and also one of its rarest, appearing on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list as endangered. Continue reading

We stayed at the Wild Grass Lodge amidst the intimidating presence of huge lenses and heavy gear.

We stayed at the Wild Grass Lodge amidst the intimidating presence of huge lenses and heavy gear.