Greg Curtis, the former deputy general counsel of Patagonia, is responsible for giving away huge sums of money to causes that are aligned with Patagonia’s history of environmental activism. Adam Amengual for The New York Times

When news broke about the company’s future, we were in awe; since then we heard little so this is a welcome update:

Patagonia’s Profits Are Funding Conservation — and Politics

$71 million of the clothing company’s earnings have been used since September 2022 to fund wildlife restoration, dam removal and Democratic groups.

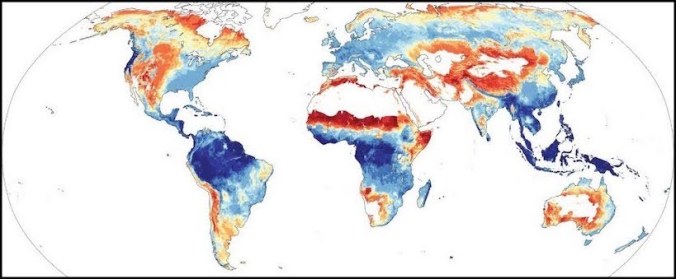

A little more than $3 million to block a proposed mine in Alaska. Another $3 million to conserve land in Chile and Argentina. And $1 million to help elect Democrats around the country, including $200,000 to a super PAC this month.

The site of the Kalivac Dam on the Vjosa River in Albania, where Holdfast has funded a major conservation project. Andrew Burr/Patagonia

Patagonia, the outdoor apparel brand, is funneling its profits to an array of groups working on everything from dam removal to voter registration.

In total, a network of nonprofit organizations linked to the company has distributed more than $71 million since September 2022, according to publicly available tax filings and internal documents reviewed by The Times. Continue reading →