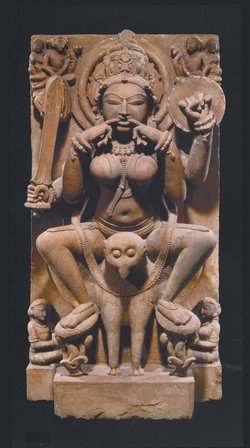

San Antonio Museum of Art. ‘Yogini’; sandstone statue, Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh, first half of the eleventh century. William Dalrymple writes that ‘in ancient India yoginis were understood to be the terrifying female embodiments of yogic powers who could travel through the sky and be summoned up by devotees who dared to attempt harnessing their powers.’

William Dalrymple, in the New York Review of Books, provides a summary of four books that should be considered essential reading to understand yoga in its proper historical context. The last few paragraphs are among the best:

…Yogis seem to have gone particularly out of control during the eighteenth-century anarchy between the fall of the Mughals and the rise of the British. This is a subject explored by William Pinch in his brilliant 2006 study of the militant yogis of the period, Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires.

European travelers of the period frequently describe yogis who are “skilled cut-throats” and professional killers. “Some of them carry a stick with a ring of iron at the base,” wrote Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna in 1508. “Others carry certain iron diskes which cut all round like razors, and they throw these with a sling when they wish to injure any person.” A century later the French jewel merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier was describing large bodies of holy men on the march, “well armed, the majority with bows and arrows, some with muskets, and the remainder with short pikes.” By the Maratha wars of the early nineteenth century, the Anglo-Indian mercenary James Skinner was fighting alongside “10 thousand Gossains called Naggas with Rockets, and about 150 pieces of cannon.”

Pinch focuses in particular on the well-attested case of Anupgiri, a Shaivite ascetic and mercenary warlord who led a large army of killer yogis and fought with both modern weaponry and spells: Mahadji Shinde, a rival leader of the time, was convinced that Anupgiri had attacked him with a painful case of boils through his “magical arts.” Nor was Anupgiri necessarily a champion of Hindu interests: “Far from thinking of themselves as the last line of defense against foreign invaders, armed ascetics in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century served any and all paymasters,” writes Pinch. Though he sometimes fought with the Hindu Marathas, at other times Anupgiri worked for the Mughal emperor.

Indeed in 1803 his last act, as Pinch shows, “was to enable the Maratha defeat at the hands of the British…and, thereby, the British capture of Delhi, an event that catapaulted the Hon’ble [East India] Company into the role of paramount power in southern Asia—and ultimately the world.”

Through this complex jungle of rival interpretation, Debra Diamond leads the visitor to “Yoga: The Art of Transformation” with the steady tread of the umpire.

The show opens with images of wizened ancient ascetics: Gandharan Buddhist images of lean dreadlocked sages found in the tribal areas between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and a beautiful Kashmiri ivory of the fasting Buddha. A room is devoted to a series of fabulously voluptuous flying yoginis occupying that peculiarly Indian space between the sacred, the sensual, and the utterly frightful.

Ironically it is only with the coming of the Muslims, in Indo-Islamic art, that we see for the first time what a modern practioner of yoga would recognize as an asana. But perhaps it is the yogis’ post-Mughal glory days of the eighteenth century, once thought to be a period of artistic decadence, that gives this show its highlights. The period of Nath power in Jodhpur, and Nath prominence in nearby Jaipur, led to attempts by artists in both cities to explain their understanding of the world in what are perhaps the supreme examples of the art of yoga: two vast, awesome purple-gold images of the Cosmic Body, with the sun on one eye, the moon on the other, including a representation of the relationship of the macrocosmic to the individual entitled Equivalence of the Self and the Universe.

It was under the guidance of these power-hungry Nath gurus that painting in Rajasthan transformed itself into something utterly remarkable, reaching heights of Rothko-like abstraction and mystical strangeness that predate by more than a hundred years many of the experiments of twentieth-century European and American art. Cosmic oceans of gold hint at states of heightened mystical consciousness; Mondrian-like fields of color are divided by frames of pure red; esoteric ideas take wing in sublime forms of fabulous, dreamlike intensity. Cosmic oceans lap against figures incarnating divine principles such as Purusha(Consciousness) and Prakriti (Matter). These are images that do not tell religious stories as much as attempt to explain the great questions of human existence: What are we doing here? How did we come? Who created us? Where are we going?

The penultimate room of the show examines the story of how yoga moved west between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. From the black-and-white photographs of early British Orientalists to 1940s circus posters for “Koringa—THE ONLY FEMALE fakir IN THE WORLD,” the show ends by telling a story of cultural misunderstanding, as the complex and sometimes contradictory body of yogic knowledge was cleaned up and rebranded as a vogueish health trend open to all—men and women, Indian and foreigner—to be marketed to a sometimes credulous Western public through celebrity yoga faddists beginning with Marilyn Monroe in the 1950s. It was only at this very late point, under the influence of Swedish body building, gymnastics, and British military drill, that it became a method of fitness: almost all pre-twentieth-century Indian yoga involved staying for a prolonged period in one asana, not moving rapidly from one to another in a yogic workout.

Today it is estimated that around 20 million Americans have performed yoga. It is a fitting end to the show, therefore, that remarkable 1940s black-and-white film footage of Krishnamachrya and his youthful disciple Iyengar, inventor and exporter of Iyengar yoga, is shown in a room where visitors are encouraged to bring their yoga mats and perform their asanas within the exhibition space. They became part of one of the most stunning shows of Indian art ever to be displayed in the US.

Read the whole article here.

Wow. Very eye opening. Thanks for this. Interesting how a lot of spiritual traditions have violent histories.

Pingback: Yoga – Popular and Partisan in Nature? | Raxa Collective