Who gets to decide what is worthy of conservation, and what is not? I am given reason to think about this on a regular basis, given the work that we have been doing for the last two decades. There is no one answer, of course, but I conclude regularly that it comes down to very deep personal experiences–those which lead individuals to alter the path of their lives and thereby have an impact on the conservation of something they have come to care deeply about. John Muir, Teddy Roosevelt and others come to mind on the larger scale of this line of thinking.

Reading one of our other blog posts today, I was taken back in time to pre-India workdays, 2008-2010. Milo, I had forgotten until just now, had a chance to wrestle firsthand with one of Patagonia’s most important conservation issues, and it is fair to say that what he is doing today is influenced by intense experiences he had in Patagonia, followed by a couple of years living with us in India. That would be an example of a smaller scale of this line of thinking. Same goes for the story I just read, and when I look at the photo above, and the one below, I am reminded that sometimes an image alone, or a series of images like these, can lead to this same path-changing epiphany.

I have family in the vicinity of this story’s subjects, and am thinking just now that I have not made a visit to that family in too long; time to plan a visit? The thought is now lodged deeply in my thinking.

Just a thought like that can alter our plans, but it is tough to resist when I read about these images (please read the whole item at the source):

The critic Greil Marcus has written that “forgetting and disappearance” are the engines of the romance in American folk music. Folk players, at the same time, are inheritors and couriers of memory—partaking of a great archive of long-held recollections. The true story behind an American folk song may be elusive, and yet the musical tradition hands these tunes forward, not unlike the family watch.

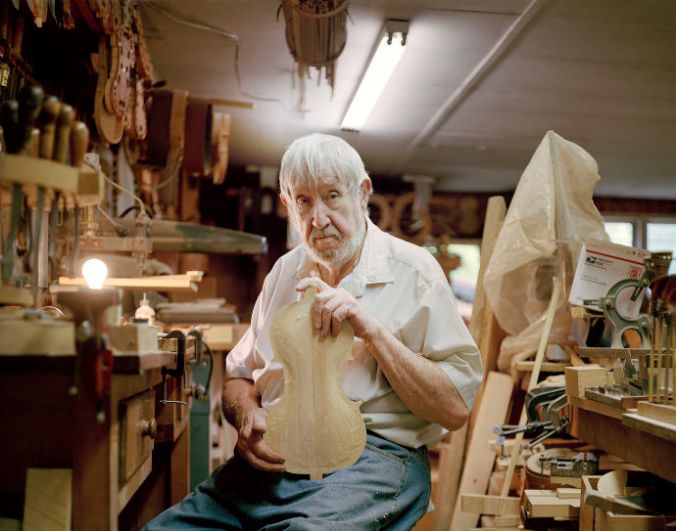

Rachel Boillot has been photographing old-time musicians of the Cumberland Plateau, in rural, eastern Tennessee, for two years. First hired as a contract documentarian by a small, non-profit record label working to preserve the regional old-time tradition, she found herself enthralled by, and “tremendously welcome” among, the local players and their community—the people she calls the “elderly bearers of tradition.” Boillot now works as an assistant producer and designer for that label, Sandrock Recordings, and she seems keenly aware that in her photographs—of the artists, their homes, and their landscape—she is telling stories about storytellers. “The ballads, in particular … It’s a narrative medium,” she says, “a marriage of creative impulses to make, and to document and preserve one’s foothold in the world.” This documenting, as in her own photography, she told me, takes “mysterious liberties” in service of “delivering the most true cultural narrative we know.”…

Intangible heritage, seemingly obviously and seemingly understandably, gets less attention and effort of conservationists than the Grand Canyons of the world. But when I read an article like this I am reminded that all over the place there are others working on important conservation initiatives and it is up to each of us to decide whether and how, if at all, to get involved, to support any given initiative in some manner. Look at that face above; try to resist.