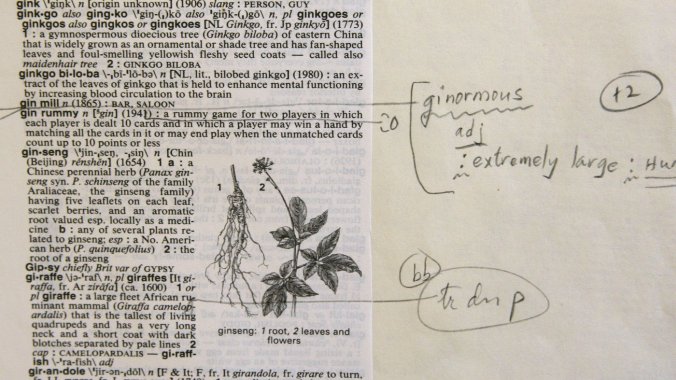

A galley proof shows some of the work that went into adding “ginormous” to Merriam-Webster’s 2007 collegiate dictionary. Charles Krupa/AP

The Case Against the Grammar Scolds

The lexicographer Kory Stamper’s new book, Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries, is an eloquent defense of a “live and let live” approach to English.

Louis du Mont / Getty

These are boom times for linguistic pedantry. Never before have there been more outlets for opinionated humans to commiserate about the absurdities of “irregardless” or the impropriety of “impact”-as-a-verb or the aggressive affront to civil society that is the existence of the word “moist.” This is an age that found Bryan Henderson, Wikipedia editor and empowered peeve-haver, taking all the instances he could find of the phrase “is comprised of,” within the vast online encyclopedia, and replacing them with “is composed of” or “consists of”—more than 40,000 word-swaps, in all. It’s an age, too, that found Lynne Truss, author of the usage polemic Eats, Shoots & Leaves,garnering plaudits and book sales by offering readers rallying cries like this one: “If you still persist in writing, ‘Good food at it’s best,’ you deserve to be struck by lightning, hacked up on the spot and buried in an unmarked grave.”

The vitriol is ironic—and, yes, I do mean ironic, Alanis-wise and otherwise—and not merely because it puts the pendants in a precarious place, karmically. (The subtitle of Eats, Shoots & Leaves, one might point out, itself contains a usage error: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation might more properly be written as “The Zero-Tolerance Approach.”) The irony is broader: To engage in such peevery, playful or otherwise, is also to ignore the long, chaotic, and deeply creative history of the English language. It is to assume that someone’s adherence to the moment’s current rules of usage is a signifier of that person’s education and worth. It is to assume, on the flip side, that to violate those rules is also to commit a very particular kind of violence against English and, by extension, its many speakers.

Well, you know what they say about assumptions. Jane Austen, it turns out, employed the possessive “it’s” in her writing, and still managed to die a relatively dignified death. Thomas Jefferson used such an “it’s,” too. So did Abraham Lincoln, those four score and many more years ago. Even David Foster Wallace, master of contemporary English and self-proclaimed linguistic “snoot,” committed the ultimate usage sin of the committed usage snob: He used “literally,” yep, figuratively…

Read the whole review here.