A chromolithograph of Christopher Columbus arriving at the Caribbean. Credit Louis Prang and Company/Getty Images

Thanks to Carl Zimmer for this 1493-ish story:

All by Itself, the Humble Sweet Potato Colonized the World

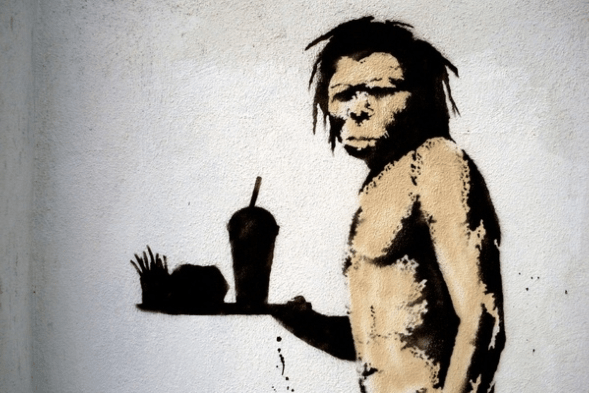

Many botanists argued that humans must have carried the valuable staple to the Pacific from South America, a hidden chapter in human history. Not so, according to a new study.

The distribution of the sweet potato plant has baffled scientists. How could the plant arise from a wild ancestor in the Americas and wind up on islands across the Pacific? Credit Karsten Moran for The New York Times

Of all the plants that humanity has turned into crops, none is more puzzling than the sweet potato. Indigenous people of Central and South America grew it on farms for generations, and Europeans discovered it when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean.

In the 18th century, however, Captain Cook stumbled across sweet potatoes again — over 4,000 miles away, on remote Polynesian islands. European explorers later found them elsewhere in the Pacific, from Hawaii to New Guinea.

The distribution of the plant baffled scientists. How could sweet potatoes arise from a wild ancestor and then wind up scattered across such a wide range? Was it possible that unknown explorers carried it from South America to countless Pacific islands? Continue reading