In early May Amie and I accompanied a group of conservation-minded investors to the southeastern tip of the Osa Peninsula, on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Over a long weekend we visited lodges in that area, but the highlight of those days was our visit to Osa Conservation. We determined to return, to understand better what this organization has accomplished and what its future plans are.

In early May Amie and I accompanied a group of conservation-minded investors to the southeastern tip of the Osa Peninsula, on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Over a long weekend we visited lodges in that area, but the highlight of those days was our visit to Osa Conservation. We determined to return, to understand better what this organization has accomplished and what its future plans are.

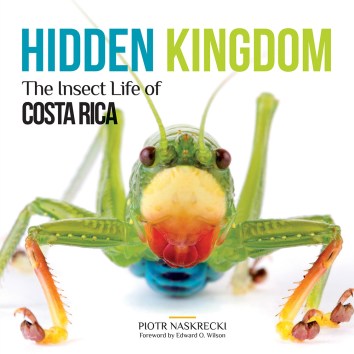

Finally we had the chance to do that this past weekend. The tree above is a good representative for why the Osa Peninsula is so important. With one of the longest life spans of any tree in this tropical forest, the abundance of diverse plants and animals that depend on the tree for life make it symbolically important as much as it is biologically important. The insect to the right, feeding on the top of a rice stalk, shifted my attention from the charismatic megaflora that made Saturday an immersive biophilia exemplar of a day–and helped me focus on acts taken by Osa Conservation to make their operation more sustainable. A one-time farm in their land holding has been rewilded. A few hectares were retained for experimental organic farming.

Finally we had the chance to do that this past weekend. The tree above is a good representative for why the Osa Peninsula is so important. With one of the longest life spans of any tree in this tropical forest, the abundance of diverse plants and animals that depend on the tree for life make it symbolically important as much as it is biologically important. The insect to the right, feeding on the top of a rice stalk, shifted my attention from the charismatic megaflora that made Saturday an immersive biophilia exemplar of a day–and helped me focus on acts taken by Osa Conservation to make their operation more sustainable. A one-time farm in their land holding has been rewilded. A few hectares were retained for experimental organic farming.

The rice strain is an example of that, but I will save that story for another day. After being fully immersed in terrestrial wonders in the forest and the farm, the beach is where I had one of life’s more profound experiences. It started at dawn on Sunday when Amie and I joined a small team from Osa Conservation who focus on turtle habitat. Our family has had multiple experiences with sea turtle nesting and egg-laying, but we have never been witness to the hatchlings returning to the sea. Yesterday was our lucky day to round out our first hand knowledge of turtle birthing life cycle. It started with a couple of spot checks on nesting sites that had been predated–in the case of the nest in the photo to the left you can see the bird tracks all around were the eggs had been ravaged.

The rice strain is an example of that, but I will save that story for another day. After being fully immersed in terrestrial wonders in the forest and the farm, the beach is where I had one of life’s more profound experiences. It started at dawn on Sunday when Amie and I joined a small team from Osa Conservation who focus on turtle habitat. Our family has had multiple experiences with sea turtle nesting and egg-laying, but we have never been witness to the hatchlings returning to the sea. Yesterday was our lucky day to round out our first hand knowledge of turtle birthing life cycle. It started with a couple of spot checks on nesting sites that had been predated–in the case of the nest in the photo to the left you can see the bird tracks all around were the eggs had been ravaged.

We may have been a mere 15 minutes too late in that case, but soon enough another nesting site was found and the surgical strike–to remove the eggs and transfer them to a hatchery where they are better protected–was under way. The protocols allow for digging carefully so that not a single egg is in danger of rupture, or even addled. They are removed one by one, counted, and placed in exactly the same formation as they were in the nest, so they can be re-nested in the hatchery as the mother turtle had laid them. Marine biologists believe that the order in the nest matters to their viability.

We may have been a mere 15 minutes too late in that case, but soon enough another nesting site was found and the surgical strike–to remove the eggs and transfer them to a hatchery where they are better protected–was under way. The protocols allow for digging carefully so that not a single egg is in danger of rupture, or even addled. They are removed one by one, counted, and placed in exactly the same formation as they were in the nest, so they can be re-nested in the hatchery as the mother turtle had laid them. Marine biologists believe that the order in the nest matters to their viability.

It was almost 6am at this point and by 8am this nest moved to safety and hatchlings from two previously moved nests were ready for release. Of all the photos I took yesterday it is difficult to choose one that is most evocative of the power of this experience. But somehow a bucket full of eggs is a candidate. We keep chickens in our yard at home, and on any given day we collect anywhere from zero to a dozen eggs from a group of 15 hens. Here one turtle had laid a hundred or so eggs (they were counted but I cannot recall the exact number now) that looked exactly like ping pong balls. Several kilometers of beach here are regularly patrolled by Osa Conservation staff, and the team of volunteers make their daily rounds to do this work.

It was almost 6am at this point and by 8am this nest moved to safety and hatchlings from two previously moved nests were ready for release. Of all the photos I took yesterday it is difficult to choose one that is most evocative of the power of this experience. But somehow a bucket full of eggs is a candidate. We keep chickens in our yard at home, and on any given day we collect anywhere from zero to a dozen eggs from a group of 15 hens. Here one turtle had laid a hundred or so eggs (they were counted but I cannot recall the exact number now) that looked exactly like ping pong balls. Several kilometers of beach here are regularly patrolled by Osa Conservation staff, and the team of volunteers make their daily rounds to do this work.

This bucketfull was taken to the hatchery further down the beach.

The signage is rustic but the message is clear.

Inside the hatchery the re-nesting begins.

The eggs removed from the nest on the beach are replaced in the hatchery nest and meanwhile Amie is taught how to extract hatchlings.

Counting again, one by one.

This time it is baby turtles coming out of the nest and into the box, and as always, seeing babies is a joy.

Seeing them walked out to the beach has its own impact.

And then the release.

133 in total, marching to the water. A race of sorts.

133 in total, marching to the water. A race of sorts.

Amie, a bird-lover, wields a stick to keep them away in case that is needed.

Amie, a bird-lover, wields a stick to keep them away in case that is needed.

And finally #133 of these Olive Ridley babies makes it to the edge of the waves.

Finally we had the chance to do that this past weekend. The tree above is a good representative for why the Osa Peninsula is so important. With one of the longest life spans of any tree in this tropical forest, the abundance of diverse plants and animals that depend on the tree for life make it symbolically important as much as it is biologically important. The insect to the right, feeding on the top of a rice stalk, shifted my attention from the charismatic megaflora that made Saturday an immersive biophilia exemplar of a day–and helped me focus on acts taken by Osa Conservation to make their operation more sustainable. A one-time farm in their land holding has been rewilded. A few hectares were retained for experimental organic farming.

Finally we had the chance to do that this past weekend. The tree above is a good representative for why the Osa Peninsula is so important. With one of the longest life spans of any tree in this tropical forest, the abundance of diverse plants and animals that depend on the tree for life make it symbolically important as much as it is biologically important. The insect to the right, feeding on the top of a rice stalk, shifted my attention from the charismatic megaflora that made Saturday an immersive biophilia exemplar of a day–and helped me focus on acts taken by Osa Conservation to make their operation more sustainable. A one-time farm in their land holding has been rewilded. A few hectares were retained for experimental organic farming.

The rice strain is an example of that, but I will save that story for another day. After being

The rice strain is an example of that, but I will save that story for another day. After being We may have been a mere 15 minutes too late in that case, but soon enough another nesting site was found and the surgical strike–to remove the eggs and transfer them to a hatchery where they are better protected–was under way. The protocols allow for digging carefully so that not a single egg is in danger of rupture, or even addled. They are removed one by one, counted, and placed in exactly the same formation as they were in the nest, so they can be re-nested in the hatchery as the mother turtle had laid them. Marine biologists believe that the order in the nest matters to their viability.

We may have been a mere 15 minutes too late in that case, but soon enough another nesting site was found and the surgical strike–to remove the eggs and transfer them to a hatchery where they are better protected–was under way. The protocols allow for digging carefully so that not a single egg is in danger of rupture, or even addled. They are removed one by one, counted, and placed in exactly the same formation as they were in the nest, so they can be re-nested in the hatchery as the mother turtle had laid them. Marine biologists believe that the order in the nest matters to their viability. It was almost 6am at this point and by 8am this nest moved to safety and hatchlings from two previously moved nests were ready for release. Of all the photos I took yesterday it is difficult to choose one that is most evocative of the power of this experience. But somehow a bucket full of eggs is a candidate.

It was almost 6am at this point and by 8am this nest moved to safety and hatchlings from two previously moved nests were ready for release. Of all the photos I took yesterday it is difficult to choose one that is most evocative of the power of this experience. But somehow a bucket full of eggs is a candidate.

133 in total, marching to the water. A race of sorts.

133 in total, marching to the water. A race of sorts. Amie, a bird-lover, wields a stick to keep them away in case that is needed.

Amie, a bird-lover, wields a stick to keep them away in case that is needed.

Another type of inspiration altogether is the tree fern, a primordial plant. The one to the right was photographed a few days ago about 250 miles south of the photo above. It is in the restoration section of a large land holding belonging to

Another type of inspiration altogether is the tree fern, a primordial plant. The one to the right was photographed a few days ago about 250 miles south of the photo above. It is in the restoration section of a large land holding belonging to