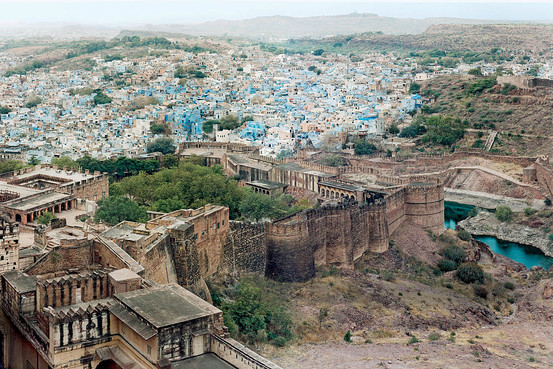

Photography by Robert Polidori. BLUE HEAVEN | Built in the 15th century by Rao Jodha, the walls of the fortress of Mehrangarh are 70 feet thick. Many of the houses of Jodhpur are painted blue to deflect the sunlight, and, according to folklore to repel insects.

The Wall Street Journal carries a feature that is quite our cup of tea:

EACH SPRING, Maharaja Gaj Singh II hosts a Sufi music festival inside his family’s vast desert fort in the Indian city of Jodhpur. From a distance, this monumental sandstone fortress, called Mehrangarh, looms over the city’s chalky blue buildings, evoking the country’s ancient and otherworldly history. And yet people fly in from across the globe because the festival—and the maharaja who hosts it—blends old India so deftly with new.

On the festival’s opening night this year, thousands of visitors filed into the fort’s crenellated stone courtyard—once reserved for royal wives—to cheer on Rabbi Shergill, a Punjabi rocker whose black turban matches his electric guitar. Singh, age 65, sat in the front row and applauded the performance along with the rest of the audience, but afterward it was he who drew the longer line of well-wishers. Foreigners slapped Singh on the shoulder, shaking his hand. Locals, who know his history better, chose to genuflect, stooping to touch his shoes.

Maharajas, or great kings, once controlled huge swaths of India, and for centuries they commissioned artworks and palaces to rival those of medieval and renaissance Europe. But like those bygone feudal lords, modern maharajas have slipped into relative obscurity—particularly after the democratic Indian government ceased to recognize their titles and cut their government subsidies, or privy purses, in 1971. A handful of maharajas are still keeping up appearances, but in reality few have successfully managed the transition into modernity. Even worse, conservators say, many of the historic sites the maharajas once oversaw are now falling into ruin or being renovated beyond recognition.

Several thousand people used to live within the walls of Farrukh Nagaur Fort, an 18th-century fortress that now sits in a booming industrial suburb of New Delhi; today, parts of Farrukh Nagar’s walls are crumbling, its only residents a colony of bats. Over in Alwar, a hilltop city in Rajasthan, the government museum within the city palace is in even rougher shape: When Dubai-based art dealer Charlie Pocock walked through it a few years ago, he found ornate silk curtains fading in the sunlight and hallways reeking of urine.

“The mind-set in India is that when things get damaged, they lose value and ought to be demolished,” says Tasneem Mehta, vice chairman of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, or Intach, a nonprofit preservation group based in New Delhi. “There isn’t a sense that we should maintain what’s sacred. We tear down and build anew.”

Photography by Robert Polidori. FAMILY AFFAIR | Gaj Singh II, known to some of his staff as the ‘Jazz Age maharaja’ for his love of jazz, in front of a portrait of his ancestor, Takhat Singh

This disregard for India’s historical treasures makes Singh’s activist approach to preservation an anomaly. Born a year after India won its independence from Britain in 1947, he was only 4 years old when he was anointed his region’s ceremonial ruler, after his father died in a plane crash. He was only 22 when the government cut off his subsidies. By his rights, Singh could have mimicked other maharajas by profiting from the sale of his birthright properties or letting them crumble to dust. Instead, he doubled down and launched a conservation program in 1972 that’s since become a national model. He started humbly, by hiring workers to muck out the bat droppings piling up in Mehrangarh, which had been closed since his family moved out in the 1930s. Then he added an entrepreneurial twist by selling that guano to local farmers as fertilizer and adapting the fort into a museum. Since then, his projects have only grown in complexity and acclaim.

Today, his second fort in nearby Nagaur, called the Fort of the Hooded Cobra, is a time-warp marvel, a sprawling complex of 18th-century palaces, temples and pools that look cared for but not overly polished. The 12th-century wall encircling it all has been repaired with a traditional paste made from sand and sheep’s hair. Its gardens are lush with plants Singh’s conservators have identified in Mughal-era miniature paintings. In the Sheesh Mahal, or mirror palace, murals of girls dancing in the rain look cleaned, but not repainted—even though their original vegetable dye has faded. “When you grow up in a desert, monsoons are a magical thing,” Singh says of the mural’s theme. “There is so much history to remember and protect here.”…

Read the rest of the story here, or click on any of the images below.

Photography by Robert Polidori. FIT FOR A KING | The steps of Umaid Bhawan Palace, from which Mehrangarh is visible. Now partly a Taj hotel, revenues are up 80 percent thanks to a boost in domestic tourism.