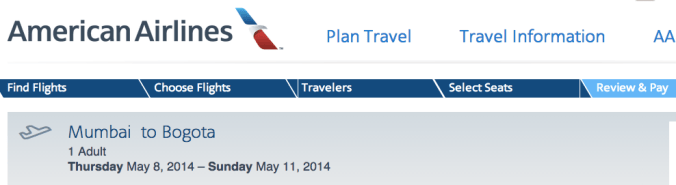

In case you do not already know about him and his writing on topics related to modern technology as it intersects with the law, the post excerpted below by Tim Wu is a good place to start. It seems possible to simultaneously agree with the specific point of this post, and also be confused with the general implication. Agreement could stem from reading enough of Tim Wu to implicitly trust his expertise. Confusion could stem from the itinerary planning screen-captured and shown above, which reminds that not everything we buy is re-sellable. Still, we click “Hold” to ponder this just a bit more to hopefully clear the fog:

…we tend to overlook the milder forms of truth-stretching that have come to shape online living, and it’s hard not to. They’re often perpetuated by big and reputable companies, like Apple, Seamless, and Amazon.

Take search. General search sites, like Google and Bing, are pretty straightforward: you type in a query and get results ranked by some measure of relevance; you also see clearly marked advertisements. This experience tends to shape our expectation that searches deliver relevant results. But the same search on sites like Amazon or Seamless turns up not only relevant results but disguised advertisements, as well. As George Packer recently wrote in the magazine, “Few customers realize that the results generated by Amazon’s search engine are partly determined by promotional fees.” GrubHub Seamless, the merged food-delivery engine, recently revealed in an S.E.C. filing that “restaurants can choose their level of commission rate … to affect their relative priority in sorting algorithms, with restaurants paying higher commission rates generally appearing higher in the search order than restaurants paying lower commission rates.”

These practices seem to run afoul of Federal Trade Commission policies. The Commission clearly declared, in 2013, that unlabeled ads posing as search results may be a form of consumer deception. Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Google’s co-founders, explained the harm of such a practice first (and best) back in 1998: “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” In other words, people will buy stuff not because it is actually better but because it’s what turns up. Of course, that didn’t stop Google, in 2012, from making its product search, Google Shopper, a pay-for-placement service, albeit one with disclosures…

…Buying products online also leads what can be called the buy-button scam, which is perpetuated even by top sites like Amazon and Apple. The other day, I decided I wanted to stream “Iron Man 3,” and Amazon told me I’d have to buy it for $14.95. It is, in fact, a common practice to present a “buy” button for movies, e-books, and digital music. But when you “buy” these digital goods, the companies maintain that, despite the big “buy” button, what they gave you is nothing more than limited permission to use it—based on fine print that creates a license, not a transfer of ownership. If Apple or Amazon can offer only what amounts to a long-term lease, the button shouldn’t say “buy.” It’s misleading.

The buy-button scam stings when it comes time to sell. Say you spent tens of thousands of dollars over the years building an extensive collection of movies on Amazon or songs on iTunes. Try selling your collection: you’ll find that what you “bought” is now worthless. If you’d spent that money on physical books, records, or CDs, you could resell them later. The would-be markets for used digital goods, like Redigi or eBay, have been sued for copyright infringement, on the premise that the goods being resold were either never sold in the first place or based on the technicality that every transfer of a digital good creates an illegal copy. Either way, you’re stuck with something that you supposedly bought but that you cannot sell.

Individually, none of these little lies are ruinous. But they add up, and they take both an economic and a cultural toll…

Read the whole post here.

Pingback: Bookstores, Breweries, Bunk | Raxa Collective