Jackson, Ron. Wine Science Principles and Applications Plate 9.1 – Cluster of grapes at different stages of rot.

The fungus Botrytis cinerea — a type of gray mold — is the kind that grows on the old berries in your fridge, but in the vineyards of Europe (and more recently some other wine-producing regions artificially infected, but more on that later) B. cinerea doesn’t always turn valuable fruit into a furry mush. Also known as noble rot, B. cinerea has the potential to positively change wine grapes, in the right conditions. Depending on a vineyard’s microclimate, infection can result in either gray rot, which essentially ruins the grapes, or noble rot, which leads to unique dessert wines such as the Tokaji Aszú of Hungary, the higher Prädikat wines of Germany, and the Sauternes of France (the most prized of which can fetch $750 a bottle!).

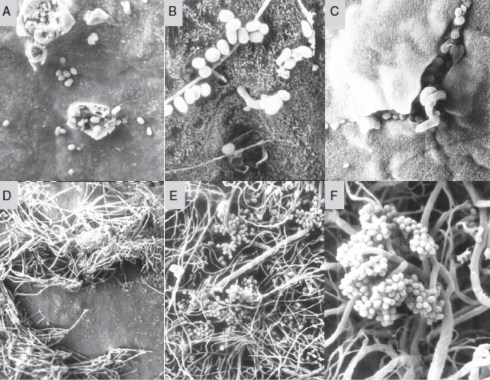

In a single vineyard there can be completely healthy grapes, grapes with gray rot, and grapes with noble rot, all in close proximity to each other. The required conditions for noble rot formation are incredibly narrow. Like with most fungi, humid conditions favor formation. However, alternating dry and rainy periods, particularly frequent morning fogs, are necessary for the formation of asexual conidia (spores). Therefore, noble rot seldom occurs in hot and dry areas, since sunny and windy conditions allow more water evaporation.

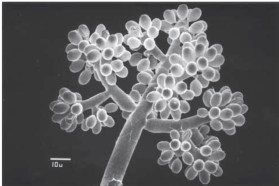

Jackson. Figure 9.1 – Grape-like cluster of Botrytis cinerea spores (conidia) produced on the spore-bearing structure, the conidiophore.

Noble rot changes the flavor, smell, and texture of wine made by grapes that have undergone a series of chemical and metabolic processes. B. cinerea is necrotrophic, which means that it utilizes dead tissue. First, certain enzymes attack the cell walls of grape skins, allowing the grapes to dehydrate more easily in dry conditions. Dehydration, which roughly cuts the weight of the grape in half, concentrates the sugar levels in the juice, making it intensely sweet. B. cinerea synthesizes the powerful aroma compound sotolon (used commercially to flavor artificial maple syrup!) that partly gives the wine its sweet, honey-like fragrance. Botrytized wine’s silky smooth mouth-feel (its more viscous texture) comes from the glycerol and other sugar alcohols that noble rot produces through enzyme reactions, and when some of these compounds are oxidized they create the golden color the wine is known for.

Magyar, Ildikó. “Botrytized Wines.” Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 63 (2011): 147-206. Figure 6.3 – (A) Botrytis conidia on the berry skin which has microinjuries in the cuticle; (B) conidia form germination tube on the epidermal layer of the berry skin; (C, D) the mycelia burst through the cuticle, and come to the surface; (E, F) heavy growth of mycelia and conidia formation on the surface.

So why is botrytized wine so expensive? First, there’s the considerable risk of leaving grapes on the vine so late in the season to over-mature. Damage by birds, heavy rains, hail, or of course gray bunch rot can preclude noble rot formation. Infected grapes must also be individually and gently handpicked. The high labor, high risk, and low volume of production of botrytized wines explains their price. But, in places where climatic conditions are unfavorable and winemaking regulations allow it, harvested grapes can be sprayed with a solution of B. cinerea spores and placed on trays where the proper growing climate is simulated. Juice has also been successfully inoculated with spores or mycelia. So far this has only been used on a limited scale in California and Australia, and is currently illegal in places like France and Germany.

Thank you to Jake Charms ’15 and Matt McGee ’15 (Cornell University) for collaborating on the original research project on noble rot that this post is based on.

Pingback: Hyphal Highways | Raxa Collective