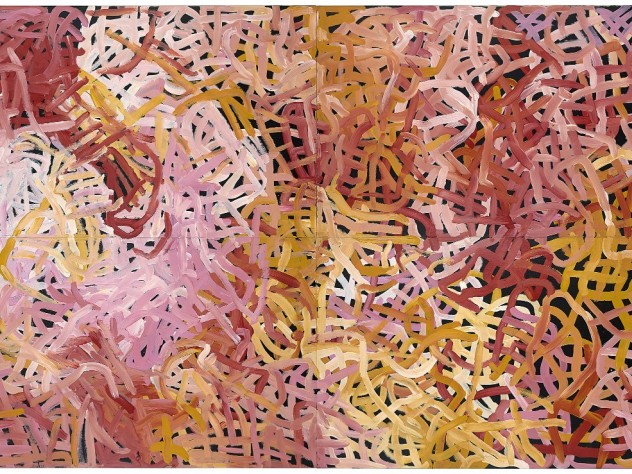

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam) (1996), on display in the “Seasonality” portion of the exhibition Everywhen © Emily Kam Kngwarray / © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISCOPY, Australia.

Cambridge, more precisely, is the location where this exhibition can be experienced:

At the Harvard Art Museums, Indigenous Australian Art and Thought on Display

THOUGH SNOW MAY FALL OUTSIDE, inside their special exhibition galleries the Harvard Art Museums host some heat from desert Australia. Composed of 70 artworks—many of which had never left their native land before now—the exhibition Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia opened on February 5.

The project was some five years in the making for visiting curator Stephen Gilchrist, an associate lecturer at the University of Sydney, and its planning required many late-night conference calls. “I felt,” he jokes, “like I was calling from the future.”

That’s appropriate, perhaps, for an exhibition so interested in how people observe the passage of time. Most of the objects—including bark paintings, works on canvas, photographs, and sculpture—were produced within the past 40 years; they are shown alongside hair belts, woven baskets, and wooden vessels collected by Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1930s. Australian anthropologist William Stanner coined the term “everywhen” in the 1960s as a way to translate the Aboriginal experience of past and future as unified and overlapping: time is cyclical and circular, rather than unidirectional and linear, and the ancestral realm pervades the present. To express this concept spatially, designer Justin Lee shaped the exhibition’s floor plan like an unending figure eight. It was further divided into four thematic sections: “Seasonality,” “Transformation,” “Performance,” and “Remembrance.”

Visitors enter through “Seasonality,” which explores human relationships with the natural world and environmental transitions. Its gallery space is anchored by a four-paneled painting by Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam), and by a trio of larrakitj, hollow log coffins for holding the bones of the dead, painted in earth pigments by Djambawa Marawili, Yumutjin Wunugmurra, and Djirrirra Wunungmurra. From memorial poles for the end of life, viewers can move on to see objects used at its beginning: the “Transformation” section displayscoolamons, multifunctional wood vessels sometimes used to cradle babies.

Gilchrist selected these items from the Peabody in part to subvert what he considers the artificial divide between art and anthropology. As he puts it, “Art and practice are like hardware and software”: they make sense only when considered together. The curator also aims for the display to be a kind of “intervention” into the Peabody’s collections. Although museums typically recorded acquisition dates and collectors’ names for accessions, they often neglected to note the names of original owners or even makers. Placing the objects in their original context—their use by actual human beings—underscores a larger lesson: “You can’t have Aboriginal art without Aboriginal people.”…

Read the whole article here.