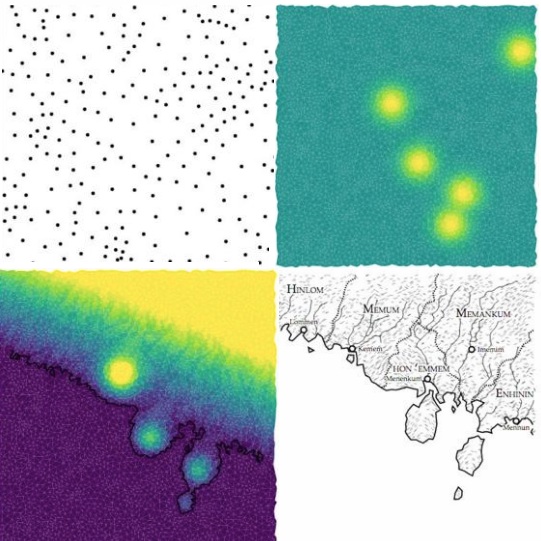

Different steps in the creation of a code-generated map that mimics real-world coastal landscape formation by erosion. Images by Martin O’Leary

There is no shortage of posts on maps here, but only one has been focused on the maps published in fantasy or fiction novels to set the scene. Two others have been linked to conservation, with one formatted in an amusing way. Then there’s my series on Icelandic cartography, starting in 1585 and continuing through 1849, then 1875, and finally 1906. But this is the first I hear about realistic fantasy maps created every hour by a bot – or computer program – coded by glaciologist Martin O’Leary and then tweeted on Twitter. And you can even go through the steps yourself and create a map of your making on his website! Betsy Manson writes for NatGeo:

As you travel northeast along the shore of southern Nimrathutkam, the first town you’ll encounter is Ak Tuh, followed by Nunrat and Nrik Mah before you reach the coastal city of Tuhuk, the largest urban area in the region of Mum Huttak.

If these sound like places out of a fantasy novel you read as a teenager, you’re not far off. Nimrathutkan is the result of an automated map generator that was inspired by those novels. The map bot, created by glaciologist Martin O’Leary of Swansea University in Wales, combines imaginary place names with fake terrain to produce fantasy worlds, tweeting a new one every hour from the Twitter account @unchartedatlas.

O’Leary came up with the idea in November when he participated inNaNoGenMo, or National Novel Generating Month. It’s a twist on National Novel Writing Month, which since 1999 has challenged writers to complete a 50,000-word novel in the month of November. Instead of writing words, NaNoGenMo participants write code that generates a 50,000-word “novel.”

“You’re trying to make a computer write a novel, so you’re looking for the most formulaic novel you can think of. And so I was thinking about these fantasy novels, and they always had these maps inside the cover,” O’Leary says, “So I started thinking, well could I make one of those maps?”

Most automated terrain generators used to create virtual worlds are based on a technique called fractal noise, a standard 3D graphics approach that’s been around since the 60s, O’Leary says. This method starts with some smooth bumps on the landscape and then adds more bumps at smaller and smaller scales. The result is something that has the same sort of texture as a real landscape. But this process has some major limitations

“It works well on the small scale, and if you’re not paying attention,” O’Leary says. “If you look at it as someone who understands where valleys come from, it doesn’t make any sense. Valleys just start and disappear, and you have no sense of how the landscape connects to itself.”

O’Leary wanted to make something more realistic. By day, he studies the effect of meltwater that collects on the Larsen C Ice Shelf in Antarctica. And as a glaciologist, he is very familiar with how landscapes form and evolve, so he started adding some real-world physics into his code.

Read the rest of the original article, which covers how the maps are generated step by step, here.