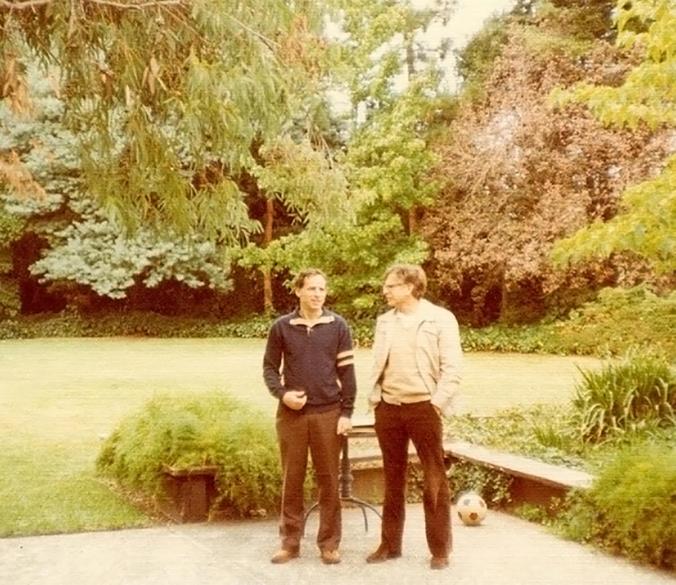

The book “The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds,” by Michael Lewis, tells the story of the psychologists Amos Tversky, left, and Daniel Kahneman, right. Photograph Courtesy Barbara Tversky

We are more and more intrigued by this book, reviewed by two who knew the subject(s) better than most:

THE TWO FRIENDS WHO CHANGED HOW WE THINK ABOUT HOW WE THINK

By Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler

In 2003, we reviewed “Moneyball,” Michael Lewis’s book about Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s. The book, we noted, had become a sensation, despite focussing on what would seem to be the least exciting aspect of professional sports: upper management. Beane was a failed Major League Baseball player who went into the personnel side of the business and, by applying superior “metrics,” had remarkable success with a financial underdog. We loved the book—and pointed out that, unbeknownst to the author, it was really about behavioral economics, the combination of economics and psychology in which we shared a common interest, and which we had explored together with respect to public policy and law.

Why isn’t the market for baseball players “efficient”? What is the source of the biases that Beane was able to exploit? Some of the answers to these questions, we suggested, might be found by applying the insights of the Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, on whose work behavioral economics greatly relies. Lewis read the review, began to take an interest in the whole topic of human rationality, and, improbably, decided to write a book about Kahneman and Tversky. He kindly even gave us credit for setting him down this path.

Though we were pleased that Lewis was taking an interest in our field, we admit to being skeptical when we heard about his book plan. Granted, Lewis has shown many times before—not only with “Moneyball” but also with “The Big Short,” his book about the real-estate market, and “Flash Boys,” which is about high-speed trading—that he can write a riveting book about an arcane subject. And we did not doubt the appeal of the book’s main characters: one of us had written several papers with Kahneman, and the other had known Kahneman and Tversky since 1977 and had collaborated with both men. (Tversky died in 1996, at the age of fifty-nine.

Kahneman, now eighty-two, is blessedly still very much with us.) Both of us had been deeply influenced by their joint work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making. Still, how was Lewis going to turn a story about their lives into the kind of page-turner that he’s known for? Kahneman and Tversky were brilliant, but they did most of their work together more than thirty years ago, and they worked primarily by talking to each other, switching between English and Hebrew. Where’s the book?

Our skepticism was misplaced. The book, titled “The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds,” captivated both of us, even though we thought we knew most of the story—and even though the book is just what Lewis had said it would be, a book about Amos and Danny, two men who changed how people think about how people think. Lewis accomplishes this in his usual way, by telling fascinating stories about intriguing people, and leaving readers to make their own judgments about what lessons should be learned. He provides a basic primer on the research of Kahneman and Tversky, but almost in passing; what is of interest here is the collaboration between two scientists. Having written several articles and one book together, we have firsthand experience in both the joys and struggles of getting two minds to speak with one voice, and the conflicts that can arise when one author is a fast writer and the other likes to linger over each word. And while one gleans a good deal about teamwork from the book, Lewis doesn’t spell the lessons out. Instead, the reader learns through observation, getting as close as anyone could to being in those closed rooms where the two men worked.

In 1968, Tversky and Kahneman were both rising stars in the psychology department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They had little else in common. Tversky was born in Israel and had been a military hero. He had a bit of a quiet swagger (along with, incongruously, a slight lisp). He was an optimist, not only because it suited his personality but also because, as he put it, “when you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice. Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” A night owl, he would often schedule meetings with his graduate students at midnight, over tea, with no one around to bother them.

Tversky was a font of memorable one-liners, and he found much of life funny. He could also be sharp with critics. After a nasty academic battle with some evolutionary psychologists, he proclaimed, “Listen to evolutionary psychologists long enough, and you’ll stop believing in evolution.” When asked about artificial intelligence, Tversky replied, “We study natural stupidity.” (He did not really think that people were stupid, but the line was too good to pass up.) He also tossed off such wisdom as “The secret to doing good research is always to be a little underemployed. You waste years by not being able to waste hours.” Managers who spend most of their lives in meetings should post that thought on their office walls…

Read the whole review here.