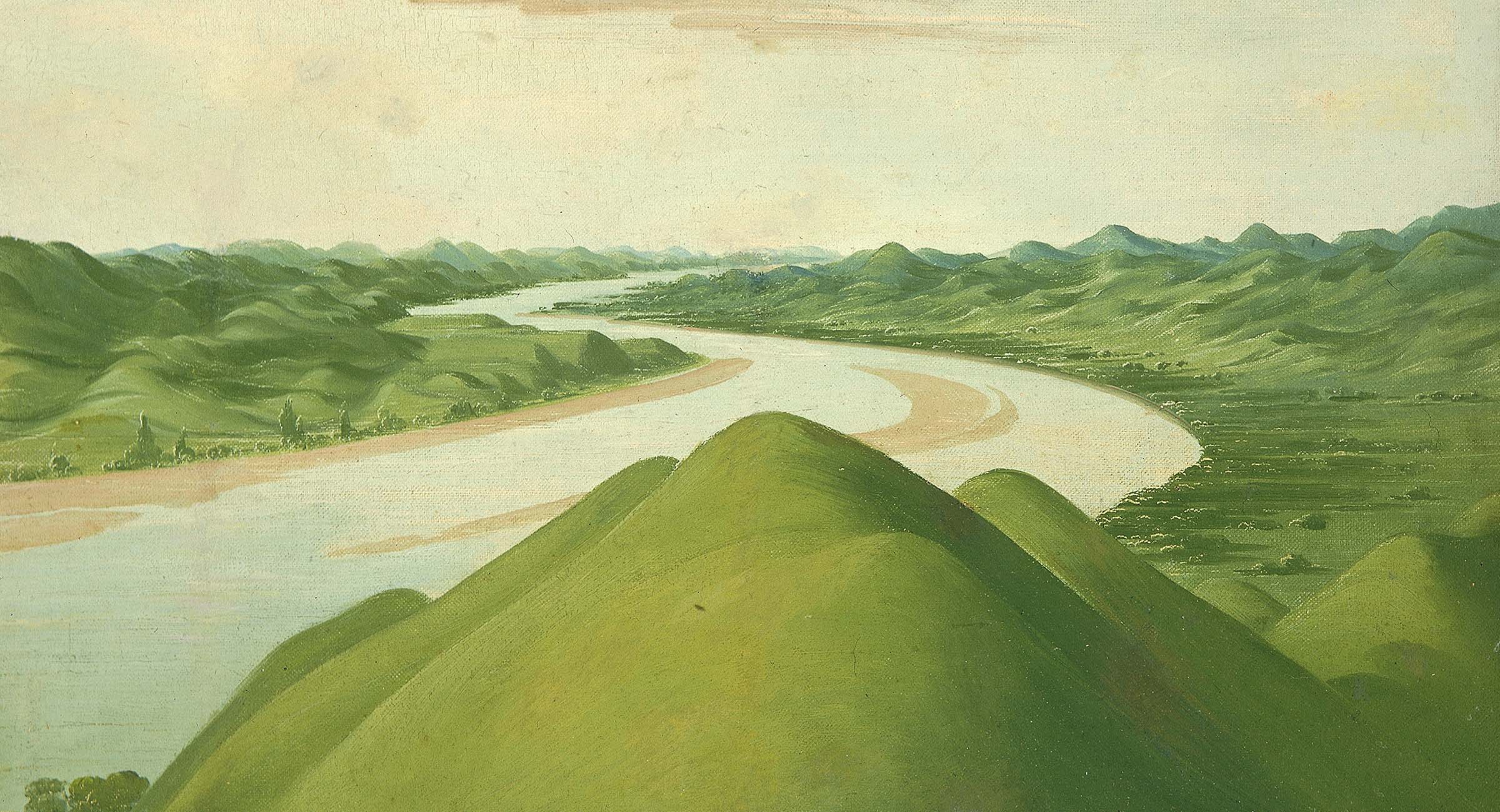

View in the “Cross Timbers,” Texas, by George Catlin, c. 1832. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

Lapham’s Quarterly, judged here only by the rare occasions when we have linked to their work, offers gem quality items of interest, such as this essay by Rosemarie Ostler:

Corn pitcher, Southern Porcelain Company, c. 1855. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2014.

The Early Days of American English

How English words evolved on a foreign continent.

English settlers faced with unfamiliar landscapes and previously unknown plants and animals in the Americas had to find terms to name and describe them. They sometimes borrowed words from Native American languages. They also repurposed existing English words and invented new terms, as well as keeping words that had become archaic in British English. As non-English-speaking immigrants began to arrive during the eighteenth century, they accepted words from those languages as well. By the time of the American Revolution, English had been evolving separately in England and America for nearly two hundred years, and the trickle of new words had become a flood.

Corn offers an example of how English words evolved in America. Before 1492, the plant that Americans call corn (Zea mays) was unknown in England. The word corn was a general term for grain, usually referring to whichever cereal crop was most abundant in the region. For instance, corn meant wheat in England, but usually referred to oats in Ireland. When American corn came to Britain, it was named maize, the English version of mahiz, an Indigenous Arawakan word adopted by the Spanish. When the first colonists encountered it in North America, however, they almost always referred to it as corn or Indian corn, probably because it was the main cereal crop of the area.

Both John Smith and William Bradford nearly always called it corn in their writings, only using maize occasionally. Smith mentioned corn frequently in his reports of his dealings with the Powhatans. In 1607, he wrote, “Our provision being now within twenty days spent, the Indians brought us great store both of corn and bread readymade.” He also used the same word to refer to the seeds brought from England: “Our next course was to turn husbandmen, to fell trees and set corn.” The seeds in question were probably wheat (or at any rate, not maize), suggesting that Smith still used corn as a general term for any staple cereal crop.

Corn was central to survival for the English settlers, so corn terms soon proliferated. In Noah Webster’s 1828 dictionary, the entries under corn cover two columns. These include the terms corn basket, corn blade, corn cutter, corn flour, corn field, cornmill, and cornstalk, among others. Webster defined corn the way the English do, as a cover term for any grain, but noted, “In the United States…by custom it is appropriated to maize.”

Other corn-related words that came into the language early on are succotash, hominy, and pone, all from Algonquian languages. In his narratives, Smith referred to “the bread which they call ponap,” and also described “homini” as “bruised Indian corn pounded and boiled thick.” The terms roasting ear, johnnycake, and hoecake (both cakes made from cornmeal) were all in use by the eighteenth century.

Much of the landscape of North America was new to the English, so many early word inventions applied to the natural world. Often these simply combined a noun with an adjective: backcountry, backwoods (and backwoodsman), back settlement, pine barrens, canebrake, salt lick, foothill, underbrush, bottomland, cold snap. Plants and animals were similarly named, for instance, fox grape, live oak, bluegrass, timothy grass, bullfrog, catfish, copperhead, lightning bug, garter snake, and katydid (a grasshopper named for the sound it makes). All were part of the vocabulary by the mid-eighteenth century. Other descriptive landscape names included clearing, rapids, and bluff.

Read the whole essay here.