Yesterday, in our continued quest to consider the future of a family dairy farm, we visited what must be the largest such farm in central Costa Rica. At 7,545 feet above sea level overlooking the valley from the northern slope, it may also be the highest.

It has eight times the land and double the cows compared to where we are based, 10 miles north and about 1,000 feet lower in altitude. That farm also has dairy goats. More on other implications of the visit later. Here, a quick note on feed. We had noticed on the dairy where we live that pineapple is part of the diet of the cows.

It has eight times the land and double the cows compared to where we are based, 10 miles north and about 1,000 feet lower in altitude. That farm also has dairy goats. More on other implications of the visit later. Here, a quick note on feed. We had noticed on the dairy where we live that pineapple is part of the diet of the cows.

The dairy manager had explained that this is an important part of the nutritional mix. Despite our surprise we had not asked more about it. Yesterday we did, and the answer was another surprise. Milk production rises 10% or more with the pineapple added to the feed. The animals are healthier because of the fiber content of the fruit, compared to cows eating grains such as corn or soy. Plus, the methane bi-product is significantly decreased. Food produced in a dairy making this dietary change represents one small step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The dairy manager had explained that this is an important part of the nutritional mix. Despite our surprise we had not asked more about it. Yesterday we did, and the answer was another surprise. Milk production rises 10% or more with the pineapple added to the feed. The animals are healthier because of the fiber content of the fruit, compared to cows eating grains such as corn or soy. Plus, the methane bi-product is significantly decreased. Food produced in a dairy making this dietary change represents one small step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In the type of coincidence I never expect, but always enjoy, this article was near the top of my news feed today. Thanks to Judith Lewis Mernit and colleagues at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies for take my yesterday’s lesson and adding some important detail:

Emissions from the nearly 1.5 billion cattle on earth are a major source of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Now, researchers in California and elsewhere are experimenting with seaweed as a dietary additive for cows that can dramatically cut their methane production.

Holstein cows feeding at a dairy farm in Merced, California. MARMADUKE ST. JOHN / ALAMY

The spring morning temperature in landlocked northern California warns of an incipient scorcher, but the small herd of piebald dairy cows that live here are too curious to care. Upon the approach of an unfamiliar human, they canter out of their barn into the already punishing sun, nosing each other aside to angle their heads over the fence. Some are black-and-white, others brown; all sport a pair of numbered yellow ear tags. Some are more assertive than others. One manages to stretch her long neck out far enough to lick the entire length of my forearm.

Scientist Ermias Kebreab has studied how to reduce cow methane emissions for more than a decade. GREGORY URQUIAGA/UC DAVIS

“That’s Ginger,” explains their keeper, 27-year-old Breanna Roque. A graduate student in animal science at the University of California, Davis, Roque monitors everything from the animals’ food rations to the somatic cells in their milk — indicators of inflammation or stress. “The interns named her. She’s our superstar.” Continue reading →

Intelligence Squared has an app that allows you to listen to their debates and lectures at your own convenience, on your phone or wherever, whenever you choose. If, like us, you have found the rewilding debate interesting, this is one you will want to listen to:

Intelligence Squared has an app that allows you to listen to their debates and lectures at your own convenience, on your phone or wherever, whenever you choose. If, like us, you have found the rewilding debate interesting, this is one you will want to listen to:

It has eight times the land and double the cows compared to where we are based, 10 miles north and about 1,000 feet lower in altitude. That farm also has dairy goats. More on other implications of the visit later. Here, a quick note on feed. We had noticed on the dairy where we live that pineapple is part of the diet of the cows.

It has eight times the land and double the cows compared to where we are based, 10 miles north and about 1,000 feet lower in altitude. That farm also has dairy goats. More on other implications of the visit later. Here, a quick note on feed. We had noticed on the dairy where we live that pineapple is part of the diet of the cows. The dairy manager had explained that this is an important part of the nutritional mix. Despite our surprise we had not asked more about it. Yesterday we did, and the answer was another surprise. Milk production rises 10% or more with the pineapple added to the feed. The animals are healthier because of the fiber content of the fruit, compared to cows eating grains such as corn or soy. Plus, the methane bi-product is significantly decreased. Food produced in a dairy making this dietary change represents one small step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The dairy manager had explained that this is an important part of the nutritional mix. Despite our surprise we had not asked more about it. Yesterday we did, and the answer was another surprise. Milk production rises 10% or more with the pineapple added to the feed. The animals are healthier because of the fiber content of the fruit, compared to cows eating grains such as corn or soy. Plus, the methane bi-product is significantly decreased. Food produced in a dairy making this dietary change represents one small step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

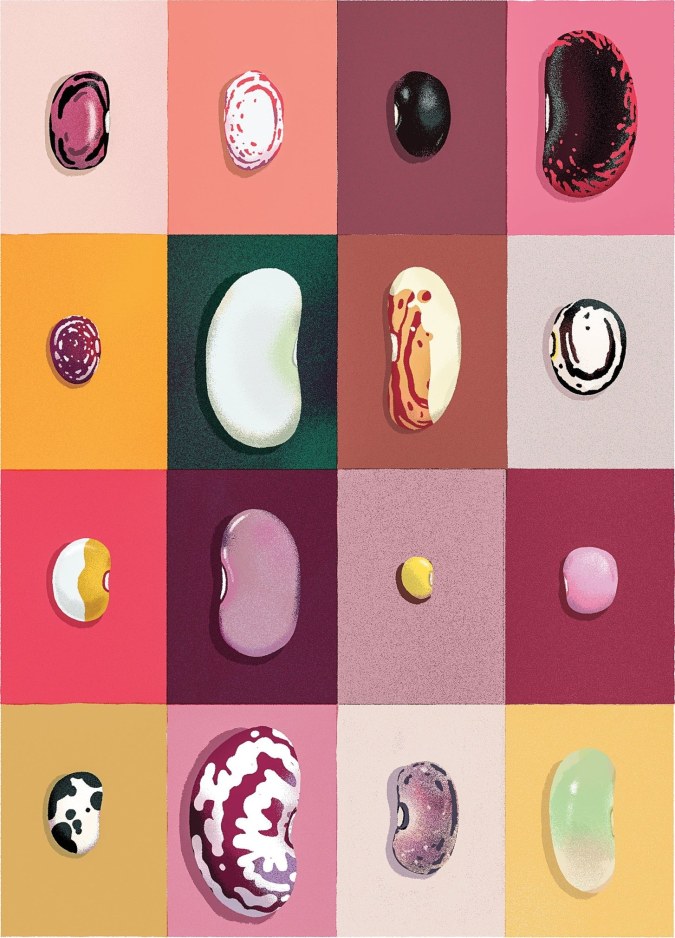

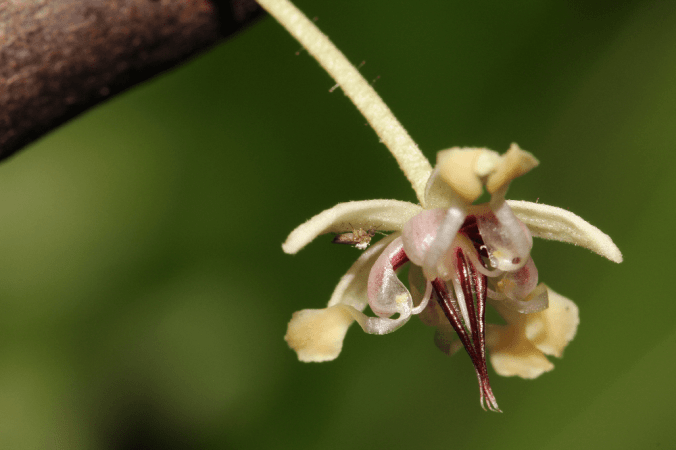

Farm.One is New York City’s grower of rare herbs, edible flowers and microgreens for some of the best restaurants in the city. Our Edible Bar and Tasting Plates make these fresh, exciting ingredients available for the first time in an event setting. Guests can discover botanical ingredients for the first time, with the expert guidance of our farm team. Taste ingredients on their own, or paired with cocktails and other beverages, for a colorful, flavorful and aromatic experience like no other.

Farm.One is New York City’s grower of rare herbs, edible flowers and microgreens for some of the best restaurants in the city. Our Edible Bar and Tasting Plates make these fresh, exciting ingredients available for the first time in an event setting. Guests can discover botanical ingredients for the first time, with the expert guidance of our farm team. Taste ingredients on their own, or paired with cocktails and other beverages, for a colorful, flavorful and aromatic experience like no other. This short piece by Anna Russell below

This short piece by Anna Russell below