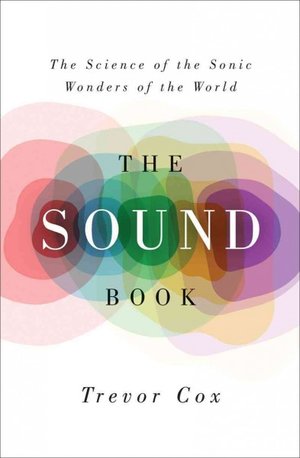

We have posted many occasions on the topic of reducing noise pollution. We care about sound, and promote the reduction of man-made versions of it when it is not needed. The author of the book (click the image to the left) is interviewed on Fresh Air and in the podcast of that conversation he explains many sound phenomena in a manner understandable to a lay person.

We have posted many occasions on the topic of reducing noise pollution. We care about sound, and promote the reduction of man-made versions of it when it is not needed. The author of the book (click the image to the left) is interviewed on Fresh Air and in the podcast of that conversation he explains many sound phenomena in a manner understandable to a lay person.

One of the most interesting findings of his scientific work will delight our many bird-oriented readers: collecting data from thousands of subjects on their sonic preferences (as well as sounds they can least tolerate) the sound of bird calls, natural or recorded, rate among the most loved by humans:

Ever wonder why your voice sounds so much better when you sing in the shower? It has to do with an acoustic “blur” called reverberation. From classical to pop music, reverberation “makes music sound nicer,” acoustic engineer Trevor Cox tells Fresh Air‘s Terry Gross. It helps blend the sound, “but you don’t want too much,” he warns.

Cox is the author of The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World. He has developed new ways of improving the sound in theaters and recording studios. He’s also studied what he describes as the sonic wonders of the world — like whispering arches and singing sand dunes. His sonic travels have taken him many places, including the North Sea, where he recorded the sound of bottlenose dolphins underwater, and down into a revolting Victorian era sewer, where he discovered a curving sound effect he’d not heard before. Continue reading