Hannah Goldfield, in this short piece about the spoon, reminds me that Bee Wilson’s book about the fork came to my attention about three years into our Kerala, India experience. I tend to favor stories about the history of something taken for granted. When it is involves foodways, I’m in. Five years ago, when that book came out, I was firmly entrenched in a new way of eating, namely with my right hand and no utensils. Today, reading about the spoon, I can relate to the author’s preference because, given the choice between spoon and fork I will choose the former. Given the choice between a meal that favors one or the other, I will choose the spoon-forward meal. But if I am somewhere eating something that hands-on is okay, keep the spoon and fork off the table.

In Praise of Eating Almost Anything with a Spoon

The introduction to the most recent version of Emily Post’s Table Setting Guides includes the following mandate: “Only set the table with utensils you will use. No soup; no soup spoon.” Sounds pretty reasonable, as far as Emily Post rules go, but I beg to differ. Who says that soup spoons are only for soup, or should even be called soup spoons at all? I have long admired the way utensils are used in parts of Southeast Asia, including Thailand: the spoon is the most important instrument, held in the dominant hand and used to bring food—soupy or otherwise—to the mouth; the fork plays a supporting role, used only to push morsels onto the spoon, and chopsticks are generally reserved for noodles. I’ve been eating Thai food this way ever since I learned about the custom, dipping spoonfuls of rice into coconut curries, herding green-papaya salad, spangled with peanuts, chili, and tiny dried shrimp, into the curvature of a spoon. It feels elegant, efficient, economical—nary a drop or a morsel is wasted. Continue reading

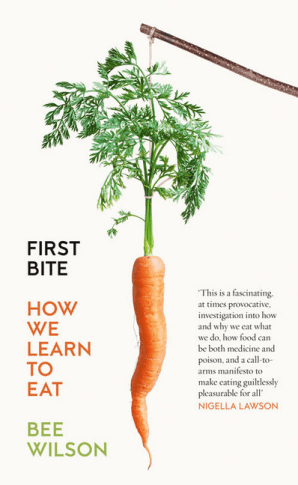

When an author of Bee Wilson’s stature publishes it is not surprising to see reviews in the news outlets that we tend to source from in these pages. For the book to the right the first we saw was

When an author of Bee Wilson’s stature publishes it is not surprising to see reviews in the news outlets that we tend to source from in these pages. For the book to the right the first we saw was