The novelist Richard Powers, I see from this review, has utilized an idea I first heard of in 2016, and that idea disappeared for a couple years (from my view, anyway). But that compelling idea is back, fictionalized and more interesting than ever:

The novelist Richard Powers, I see from this review, has utilized an idea I first heard of in 2016, and that idea disappeared for a couple years (from my view, anyway). But that compelling idea is back, fictionalized and more interesting than ever:

People see better what looks like them,” observes the field biologist Patricia Westerford, one of the nine—nine—main characters of Richard Powers’s 12th novel, The Overstory. And trees, Patricia discovers, look like people. They are social creatures, caring for one another, communicating, learning, trading goods and services; despite lacking a brain, trees are “aware.” After borers attack a sugar maple, it emits insecticides that warn its neighbors, which respond by intensifying their own defenses. When the roots of two Douglas firs meet underground, they fuse, joining vascular systems; if one tree gets ill, the other cares for it. The chopping down of a tree causes those surrounding it to weaken, as if in mourning. But Powers’s findings go beyond Dr. Pat’s. In his tree-mad novel, which contains as many species as any North American forest—17 are named on the first page alone—trees speak, sing, experience pain, dream, remember the past, and predict the future. The past and the future, it turns out, are mirror images of each other. Neither contains people.

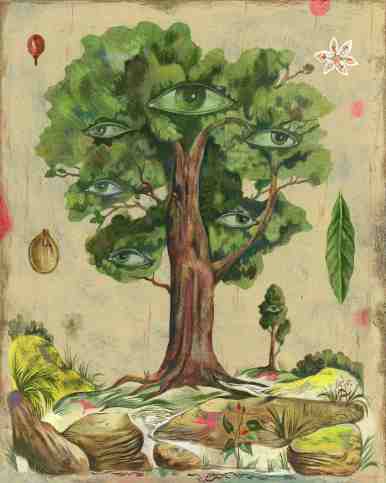

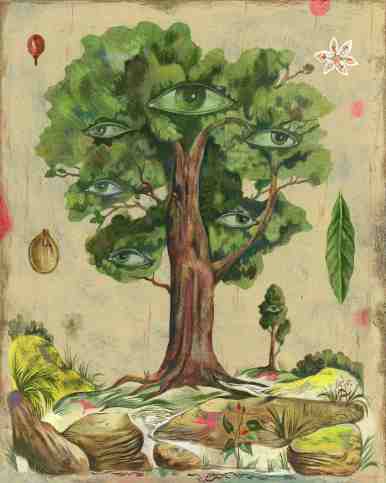

Olaf Hajek

Barbara Kingsolver’s earlier review in the New York Times started the ante on the must-read judgement that Nathaniel Rich (above) upped:

Trees do most of the things you do, just more slowly. They compete for their livelihoods and take care of their families, sometimes making huge sacrifices for their children. They breathe, eat and have sex. They give gifts, communicate, learn, remember and record the important events of their lives. With relatives and non-kin alike they cooperate, forming neighborhood watch committees — to name one example — with rapid response networks to alert others to a threatening intruder. Continue reading →

When I first linked to the work of Richard Powers it was when his previous book was being reviewed. Now he has a new book out, and from the conversation that follows it sounds like this one is a very good bookend to that one:

When I first linked to the work of Richard Powers it was when his previous book was being reviewed. Now he has a new book out, and from the conversation that follows it sounds like this one is a very good bookend to that one: