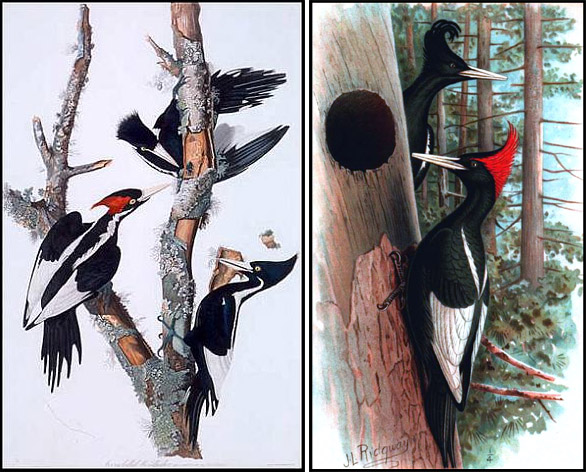

Left: Ivory Billed Woodpecker by John James Audubon;

Right: Imperial Woodpecker by John Livzey Ridgway

In the world of ornithology and bird watching, scale is as important as plentiful plumage, vivid color or song style. From Cuba’s Mellisuga helenae (bee hummingbird) to the Andean Condor, life lists are often based on superlatives. The Campephilus (woodpecker) family has its own followers, especially the larger species that have eluded scientists and amateurs alike for decades.

While in Chaihuín, part of the Nature Conservancy’s Valdivian Coastal Reserve in Chilean Patagonia, we saw the Magellanic Woodpecker, a sighting that preceded a “Stop the Jeep!” moment of excitement. Part of that excitement was based on the memory of a Cornell Lab of Ornithology film we’d recently seen about the Ivory Billed Woodpecker.

Habitat loss is a particular issue for slow breeding, specialized species like woodpeckers, and it’s telling that the upper left hand corner of the Ornithology Lab page for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) has the sad message: “No Image Available”. In the 1870s the laws protecting the ivory-bill were removed, and much of their southeastern United States forest home fell to the timber industry, and by the 1940s the bird was rarely, if ever, seen in the wild.

Mexico’s Imperial Woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) is considered to be the “mightiest woodpecker that ever lived”. Tim Gallagher, editor-in-chief of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s Living Bird magazine, has spent years in the study of these two “Holy Grail” birds, and the discovery of the rare 1950s 16mm footage taken of the Imperial was near miraculous. The scientific value of the only photographic documentation of the bird is incalculable, and Gallagher’s description of his expedition to Durango with Dutch woodpecker researcher Martjan Lammertink is poignant.

With the assistance of the American Museum of Natural History archives, graduate student Evaristo Hernández-Fernández, a Bartels Science Illustration intern was able to paint the majestic bird in it’s Sierra Madre Occidental habitat for the cover of the October issue of The Auk, the scientific journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

Having seen one member of this iconic bird family isn’t something I will easily forget. What the negative side of human activity has taken away, the beauty of human art and ingenuity has ever so slightly given back, allowing generations the opportunity to have a glimpse of the “Lord God Birds.”

Pingback: Collective Memory « Raxa Collective