Malcolm Gladwell brings to our attention an economist/planner/idea guy who might not otherwise have found his way to our reading list. In his usual writing style, Gladwell makes the man, by reviewing his biography, irresistible. Toward the end of the review, what is described as one of the economist’s key contributions provides a perfect counterpoint to these ideas. We like this guy because he chooses voice over exit (click the image to the right and it is definitely worth reading to the end):

In the mid-nineteenth century, work began on a crucial section of the railway line connecting Boston to the Hudson River. The addition would run from Greenfield, Massachusetts, to Troy, New York, and it required tunnelling through Hoosac Mountain, a massive impediment, nearly five miles thick, that blocked passage between the Deerfield Valley and a tributary of the Hudson.

James Hayward, one of New England’s leading railroad engineers, estimated that penetrating the Hoosac would cost, at most, a very manageable two million dollars. The president of Amherst College, an accomplished geologist, said that the mountain was composed of soft rock and that tunnelling would be fairly easy once the engineers had breached the surface. “The Hoosac . . . is believed to be the only barrier between Boston and the Pacific,” the project’s promoter, Alvah Crocker, declared.

Everyone was wrong. Digging through the Hoosac turned out to be a nightmare. The project cost more than ten times the budgeted estimate. If the people involved had known the true nature of the challenges they faced, they would never have funded the Troy-Greenfield railroad. But, had they not, the factories of northwestern Massachusetts wouldn’t have been able to ship their goods so easily to the expanding West, the cost of freight would have remained stubbornly high, and the state of Massachusetts would have been immeasurably poorer. So is ignorance an impediment to progress or a precondition for it?

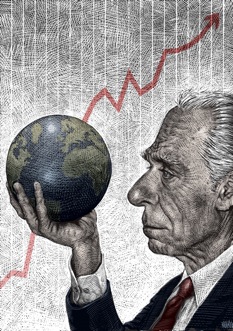

The economist Albert O. Hirschman, who died last December, loved paradoxes like this. He was a “planner,” the kind of economist who conceives of grand infrastructure projects and bold schemes. But his eye was drawn to the many ways in which plans did not turn out the way they were supposed to—to unintended consequences and perverse outcomes and the puzzling fact that the shortest line between two points is often a dead end.

Read the whole review here.

Stupendous idea (that should be core reading for all Peace/Development students), but what a man!