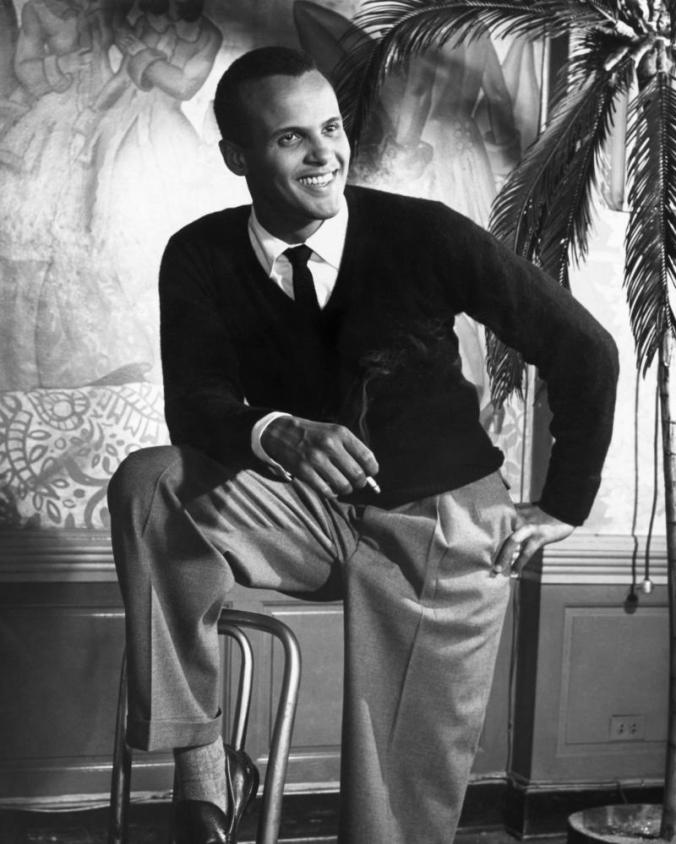

A new anthology of the work of Harry Belafonte, pictured here in the nineteen-forties or fifties, reiterates his standing in American music. PHOTOGRAPH BY BETTMANN / GETTY

There was an editorial a few days ago that alerted us to the birthdays of two buddies, each on icon in his own right, who have 70 years of solidarity in the tough times, and best of times too. It also alerted us to the time since our last post with the model mad theme, so here is one more:

HARRY BELAFONTE AND THE SOCIAL POWER OF SONG

By Amanda Petrusich

Sixty-one years ago, in 1956, Harry Belafonte recorded a version of the Jamaican folk song “Day-O,” for his third studio album, “Calypso.” It opens with a distant and eager rumbling—as if something dark and hulking were approaching from a remote horizon. Belafonte—who was born in Harlem in 1927, but lived with his grandmother in a wooden house on stilts in Aboukir, a mountain village in Jamaica, for a good chunk of his childhood—bellows the title in a clipped island pitch. The instrumentation is spare and creeping. His voice bounces and echoes as it moves closer. It sounds like a call to prayer.

The song was written sometime around the turn of the twentieth century, though to suggest that “Day-O” was formally composed in any sort of premeditated way might be overstating things. It’s a call-and-response work song, likely concocted spontaneously by overnight dockworkers cramming bunches of bananas onto ships, hot-footing it away from loose spiders, and fantasizing about rum. By 1890, the sugar trade in Jamaica had been toppled by an assortment of wars, acts of God, and political upheavals, and bananas had become the country’s primary export. “Come Mr. Tally Man, tally me banana,” Belafonte implores. “Daylight come and me wan’ go home,” his chorus chants. It is an infinitely applicable refrain, no matter what your metaphorical banana might be, or which cocktail seizes your imagination come quitting time. “Me wan’ go home” is perhaps as universal a plea for freedom as we’ve got.

“Day-O” is so suffused with joy and pathos—that age-old human mishmash—that almost anybody with an actively beating heart sounds awesome singing it. Incredibly, in 1957, five more artists made it onto the U.S. Top Forty with their versions; these range from rich and enveloping (the jazz singer Sarah Vaughn) to unsettlingly polite (the folk-pop band The Tarriers). One of the writing credits for Belafonte’s iteration goes to Irving Burgie, or Lord Burgess, a Brooklyn-born songwriter of Barbadian descent. Belafonte’s friend and collaborator, the novelist Bill Attaway, introduced Belafonte to Burgess, whom Attaway had called “the black Alan Lomax—a walking library of songs from the islands.” The trio camped out in a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, where Belafonte was performing a string of shows, and fiddled around with “Day-O,” which was known at the time as “The Banana Boat Song,” or “Hill and Gully Rider.”

“None of us had any idea, when we recorded it, that it would be spun off as a single,” Belafonte admits, in his 2011 autobiography, “My Song.” “Day-O” went to No. 5 on the charts, and “Calypso” became the first full-length record of any sort to sell a million copies. Belafonte had bickered with RCA over the cover. The first mockup he saw featured his body with “a big bunch of bananas superimposed on my head. I looked like Carmen Miranda in drag, only in bare feet, with a big toothy grin, as if I were saying, ‘Come to dee islands!’ ”

On March 1st, Belafonte will turn ninety. This week, Sony Legacy is releasing “The Legacy of Harry Belafonte: When the Colors Come Together,” a new anthology of his work. It’s a beautiful, manifold collection, and reiterates Belafonte’s standing as one of America’s most vital and insurrectionary folk singers. There is video of Belafonte performing his song “Matilda” in 1966, at a benefit for Martin Luther King, Jr. He is lithe and balletic, slinking easily about the stage, like a stalk of tall grass bending in the breeze. When it comes time for the chorus to sing, he flaps his hands at them in a gesture I have now observed hundreds of times but still cannot figure out how to describe: it is as if his hand is attached to strings being tugged on from above. Belafonte came of age as a vocalist in an era in which tone and modulation were paramount, watched as those foundations were successfully subverted, and then grew expert at drawing from both customs. This gives his work a tense and singular dynamism.

Prior to “Calypso,” Belafonte worked as a stage actor and a jazz singer, but in the early nineteen-fifties he became gripped by vernacular music, and particularly by the idea that a folk song could be an engine of actual social change. In “My Song,” he tells a story about seeing the folk singers Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly perform at the Village Vanguard, and being so remade by the experience that he arranged for a pilgrimage to the Library of Congress, in Washington, to listen to the thousands of field recordings that Alan Lomax had collected and archived there. “I just couldn’t stand the thought of going back to those mushy pop standards,” Belafonte writes. Though he had grown up in deep poverty, he fretted over his bona fides and his racially mixed origins. (His maternal grandmother was “the white daughter of a Scottish father who’d come to Jamaica to oversee a plantation for an absentee owner,” while his paternal grandfather was “a white Dutch Jew who’d drifted over to the islands after chasing gold and diamonds, with no luck at all.”) “I wasn’t even a full-fledged Jamaican, or a black from Harlem with full Afro-American roots,” he worried. “All of this mattered, deeply, in the burgeoning folk music of the early 1950s, because authenticity was what the songs were about, and an inauthentic singer, which was what I appeared to be, had no right to sing them.”…