Adam Moss has not appeared in our pages until now. Given that we lean on publications that he was the editor of, especially The New York Times Magazine, it is one reason to pay attention to this review of his new book. At The New York Times he oversaw the Magazine, the Book Review, and the Culture, and Style sections, and before that edited Esquire, all of which led to his being elected to the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame in 2019.

Adam Moss has not appeared in our pages until now. Given that we lean on publications that he was the editor of, especially The New York Times Magazine, it is one reason to pay attention to this review of his new book. At The New York Times he oversaw the Magazine, the Book Review, and the Culture, and Style sections, and before that edited Esquire, all of which led to his being elected to the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame in 2019.

The review of his book is paired with that of another, both of which enlighten on the topic of sustaining creativity over a long period. Our thanks to Alexandra Schwartz at The New Yorker for this:

The creative life is shrouded in mystery. Two new books try to discover what it takes.

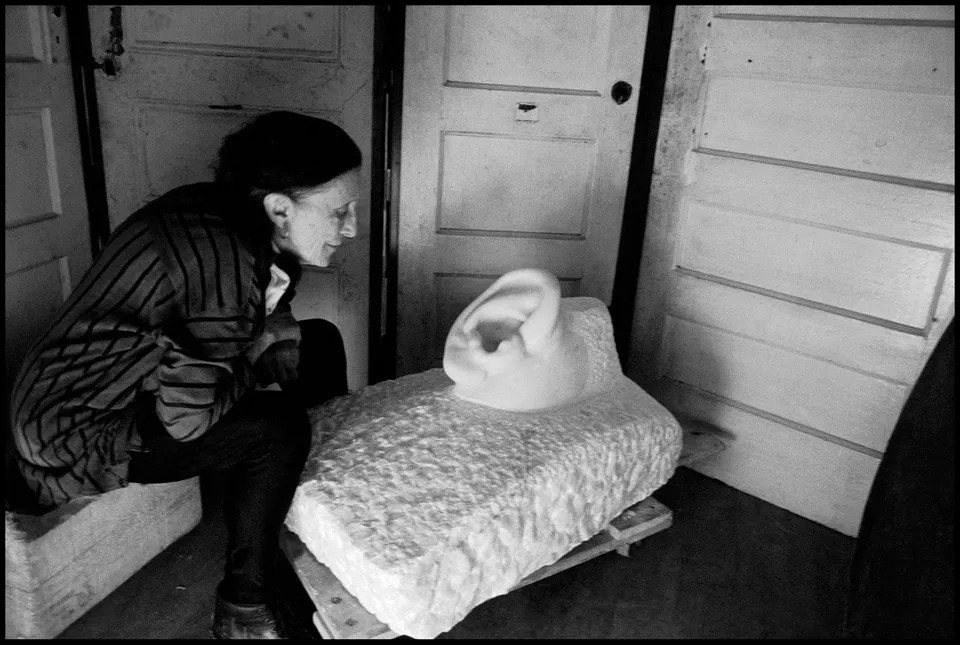

Louise Bourgeois loved to work, and she loved to talk. She especially loved to talk about her work. In the 2008 documentary “Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine,” directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach—you can watch the whole thing on YouTube, isn’t that great?—she answers questions as she chisels and draws and violently wrings scraps of material as a butcher might wring a chicken’s neck. “It is really the anger that makes me work,” she says. She has just been discussing her governess, the despised Sadie, an Englishwoman who carried on an affair with Bourgeois’s father for ten years while she lived in the family home.

“All my work of the last fifty years, all my subjects, have found their inspiration in my childhood,” Bourgeois adds. She is an old woman when she says this—wrinkled, commanding, vital—and also, it seems, forever a little girl peeping through the keyhole at Sadie and Papa, shocked and betrayed. In another video, one that has found new life bopping around TikTok and Instagram, Bourgeois sits at a small table in her Chelsea town house before a blank piece of paper. “This drawing that I am going to do now obviously stems from a fear,” she says. Anger, fear—these are the powerful horses that Bourgeois harnessed to make her art, and she rode them until she died, in 2010, at the age of ninety-eight.

How do artists sustain themselves year after year, through good times and bad? What special fuel do they use to stoke their inner hearths? This is the subject of “The Long Run: A Creative Inquiry” (Graywolf), a new book by the writer Stacey D’Erasmo. Originally, D’Erasmo tells us, her approach to the project was detached, “a little academic.” She was getting older (she is now sixty-two) and thought that she would publish an anthology of interviews with veteran artists who could give a view of the road ahead. Then she had a crisis, or a series of them, both personal and professional. “Relationships broke, friendships broke, promises broke,” she writes. “Many facets of my identity shattered.” She was denied tenure at Columbia, where she had taught for a decade, and suddenly found herself out of a job. After a lifetime spent loving women and joyously enrolled in the queer world, she coupled off with a man. Worst of all, she found that, for the first time in her working life, she was totally unable to write. “How do we keep doing this—making art?” she asks in her book’s first sentence. She really wants to know.

Well, define your “we.” The one that D’Erasmo has gathered here is a cohort of eight artists who have little in common aside from living long, creatively productive lives. There is the dancer Valda Setterfield, who performed with Merce Cunningham and went on to enjoy a decades-long collaboration with her husband, the choreographer David Gordon; the writer Samuel R. Delany, who has published more than forty books and seems to write as he breathes; and also the pioneering landscape architect Darrel Morrison, who takes the natural world for his material. The actress Blair Brown has struggled, as many actresses do, with an industry that tends to see young women as the sum of their bodies’ parts and to stop seeing older ones at all, while the abstract painter Amy Sillman experienced a creative breakthrough in her late fifties. The composer and conductor Tania Léon was born in Cuba but made her career in exile, while the musician Steve Earle, a veteran of drugs, divorce, and death, seems to be on his fourth or fifth life, trucking on with his guitar.

So D’Erasmo was gutsy. She hopped among genres; she didn’t stick to what she knew, and she is up front about that. When, for example, she feels intimidated by Léon’s music, she comes right out and says so. “I am not a gardener,” she confesses in her chapter on Morrison—but, in a way, she is. Like Morrison, who pioneered the concept of “sweeps,” in which a variety of native plants are grouped “in swaths and clusters and handfuls” to create something at once organic and spectacular, D’Erasmo plants her subjects together in unexpected arrangements, throwing in some favorite seeds of her own—a reference to Colette or Roberto Bolaño here, a look at Ruth Asawa’s sculptures there—and then steps back to see what patterns emerge.

One big thing that D’Erasmo discovers her subjects have in common is their flexibility, the ability to change along with circumstances. “A vibrant long run might be sustained not by armoring oneself inside an even bigger and more expensive fixed narrative, but by morphing through a varied series of them over many years,” she writes in her chapter on Brown. “Against the monument, the mobile. Against the hammer, the leap.” She means that it’s O.K. that Brown has never become a megastar in the Marvel universe or whatever—that, although she has played many wonderful, meaty roles over the course of her career, sometimes her phone just doesn’t ring. Acting is different from painting or writing or composing. You can’t do it alone; you have to work with what you’re given. Brown is now seventy-eight, and hasn’t had a television or film role since a four-season arc on “Orange Is the New Black” ended, in 2019. Still, she seems happy. Not long ago, she turned down a yes-dear role as someone’s wife on an HBO show because it felt too limiting. She has, D’Erasmo thinks admiringly, an “inner freedom.”

In her chapter on Sillman, D’Erasmo doubles down on the flexibility point. Artistic survival, she says, is fundamentally Darwinian; long-term success requires adapting to the environment at hand. For D’Erasmo, that means the American university, where so many artists and writers today make their living. D’Erasmo reserves a righteous anger for the precarity of academia, which she experienced firsthand, and for its increasingly corporate, donor-flattering imperatives. But she also seems to genuinely like her students, as do many of her subjects. Delany, who projects a prickly, detached persona when asked to discuss his own work, tears up while speaking about teaching. Sillman does him one better; when she was on the faculty at Bard, she says, she considered not only her teaching work but indeed her job as a department co-chair as part of her actual art practice. This sounds both noble and nuts—did Wallace Stevens think of insurance law as part of his poetry? But it makes a kind of sense. You’re gonna have to serve somebody, Bob Dylan sang, and that is what D’Erasmo thinks, too. “Michelangelo had to be able to deal with the pope (which often did not go well),” she writes. “Artists and writers working now have to be able to deal with the dean (which also often does not go well).” Michelangelo may have had it worse. Imagine the dean telling you that you have to paint the ceiling…

Read the whole review here.