With help from books and YouTube, Abe Marcus (left, pictured with Yasamin Sharifi, center, and Tsu Isaka) has been learning how to operate a coal-powered, hand-cranked forge found on the property. Lauren Migaki/NPR

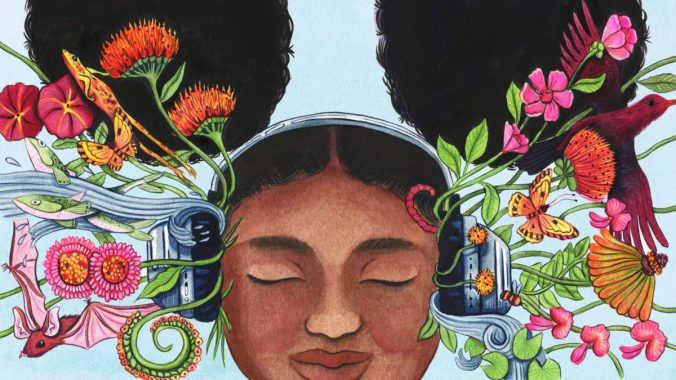

There is a great story shared yesterday on the National Public Radio (USA) website, told in unusually long form for that outlet, by Anya Kamenetz. I look forward to more stories by this journalist — she relates a story that is as far away from my own experience as I can imagine, but I feel at home in it. The picture to the right, from near the end of the story, hints at one reason. But it is not that. Nor is it the fact that I witnessed the birth and evolution of a similar initiative in Costa Rica.

I taught a field course in amazing locations (2005 in Senegal, followed by Costa Rica in 2006 followed by Croatia, India, Siberia and Chilean Patagonia), but that bore little resemblance to the initiative in this story. All those factors may help me feel at home in this story, but mostly I relate to it as a story told well for the purpose of understanding the motivations of a social entrepreneur and incidentally her commitment to experiential learning.

Marcus stands in front of the massive vegetable garden at The Arete Project in Glacier Bay, Alaska. Lauren Migaki/NPR

In Glacier Bay, Alaska, mountains rush up farther and faster from the shoreline than almost anywhere else on the planet. Humpback whales, halibut and sea otters ply the waters that lap rocky, pine-crowned islands, and you can stick a bare hook in the water and pull out dinner about as fast as it takes to say so.

This is the place 31-year-old Laura Marcus chose for her Arete Project. Or just maybe, this place chose her.

The Arete Project takes place in the remote wilderness of the Inian Islands in southeast Alaska.

Lauren Migaki/NPR

Arete in Greek means “excellence.” And Marcus’ Arete is a tiny, extremely remote program that offers college credit for a combination of outdoor and classroom-based learning. It’s also an experiment in just how, what and why young people are supposed to live and learn together in a world that seems more fragile than ever. It’s dedicated, Marcus says, to “the possibility of an education where there were stakes beyond individual achievement — where the work that students were doing … actually mattered.” Continue reading →

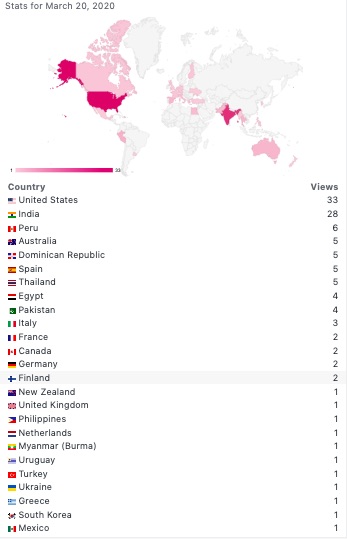

To the left you can see yesterday’s viewership of our posts, by country. Viewership has recently been low, for obvious reasons. It has made me wonder whether we should take a hiatus. My counter-thought is, if on a day like yesterday, just one person visited this site and found something of value, we should continue. As of today there have been 696,713 views of all of our posts since we started in mid-2011. Yesterday someone viewed

To the left you can see yesterday’s viewership of our posts, by country. Viewership has recently been low, for obvious reasons. It has made me wonder whether we should take a hiatus. My counter-thought is, if on a day like yesterday, just one person visited this site and found something of value, we should continue. As of today there have been 696,713 views of all of our posts since we started in mid-2011. Yesterday someone viewed

I mentioned his coffee

I mentioned his coffee  venture

venture