Michelle Nijhuis came to my attention in 2014 by making me laugh. She has since been featured in our pages too many times to count. Now, after all those previous (nine, but who’s counting?) shout outs I thank her for bringing to my attention a book that makes me smile at the same time it makes me wince:

…Though Beyond the Sixth Extinction can be enjoyed solely for its dystopian yuks, its elegant paper sculptures tell a deeper story. The book doesn’t spend much time blaming humans for the world it imagines, or spell out exactly what has befallen Homo sapiens during the nearly three millennia between 2019 and 4847. But it does hint at a world in which the human footprint has been radically reduced. Chicago transformed into the diminished district of Cago, and life to some extent has moved on without us…

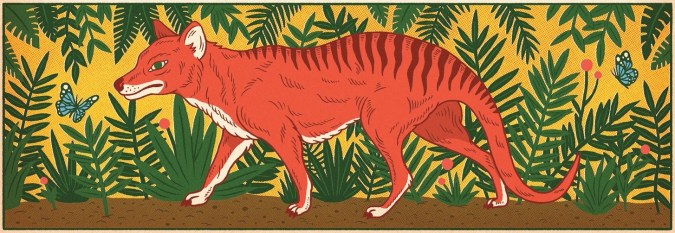

The rex roach is one of many lively species that inhabit the Cago district in the year 4847. PAPER ENGINEERING © SHAWN SHEEHY / CANDLEWICK PRESS

When I first saw something vaguely akin some years ago, the creative approach to a dark topic made me smile. This time, I am drawn in by an artist’s unique vision of the future as it relates to the natural world, and my reaction is to think while smiling.

When I first saw something vaguely akin some years ago, the creative approach to a dark topic made me smile. This time, I am drawn in by an artist’s unique vision of the future as it relates to the natural world, and my reaction is to think while smiling.

So, off to Candlewick Press (click the image of the book to the left). Even though I am not inclined to dystopia, I like what the author / artist / pop-up engineer says about what looks to be its hand-made progenitor:

In his book The Sixth Extinction, Richard Leakey describes five major catastrophes in Earth’s history that led to significant extinctions—the last of which was the meteor impact that eliminated the dinosaurs. He theorizes that the sixth big extinction has already begun, and that it is human-authored. Be it through over-hunting, global warming, or habitat destruction, humans have the power to destroy species at alarming rates.

Evolutionary theorists like Stephen Jay Gould have studied and written about the speciation that followed these previous die-offs, like the mammalian bloom that followed the extinction of the dinosaurs. I myself wonder which species might survive and flourish in a new environment if humans are successful in instigating a profound die-off. I wonder what anatomical adaptations they might acquire in their proliferation.

All of the creatures in this book are based on organisms that have high survival ratings, including: ubiquity (or nearly so), omnivory (linked to high intelligence), adaptability (especially to human-made habitats), and escape mobility. Since I am interested in representing a single system, they also had to have the potential to entertain plausible interdependencies.

Though the content of this book is bleak, the tone is cautiously optimistic. Some ecological theorists believe that humans—being the most adaptable species in the history of the planet—will be the very last species to be exterminated, but there is still hope that a sustainable balance can be found between human resource use and the resource use of everything else. Continue reading

When I see the name Peter Matthiessen the first thing I think of is a recording of his voice on my telephone ten years ago. I knew he would be passing nearby and had invited him to see

When I see the name Peter Matthiessen the first thing I think of is a recording of his voice on my telephone ten years ago. I knew he would be passing nearby and had invited him to see