This week, the time has come for me to officially lay out some of the terms of my honors history thesis that I have been writing about for a few months now. Although this “hypothesis,” or explanation of what I expect to argue, won’t set my focused topic in stone, it will certainly be instrumental in guiding me at least in a broad sense as I move forward with writing this semester, and it will also help show my advisors what path I plan to take. Without further ado, here is my thesis hypothesis in a 400-word nutshell. Continue reading

Iceland

The Big Thaw

2009 Jökulsárlón, Iceland. Destined to melt, an 800-pound chunk of ice glows in moonlight, from the National Geographic story “Meltdown.”

On our pages we like to narrate stories, sometimes stories that people would rather not hear. If a “picture is worth a thousand words” then James Balog’s images for National Geographic tell a poignant narrative.

The pictorial language has the unique ability to penetrate the human heart and mind and photography has the power to alter the course of civilization through perception. My main subject has been the collision between human needs and nature, it’s always seemed to me that’s one of the pivotal issues of our moment in history Continue reading

Journey to the Center of the Earth, Via Iceland

Snæfellsjökull, Iceland. Photo © Mariusz Kluzniak

When I explain my honors thesis subject to those who ask about it, not a few of them ask if I plan on looking at Jules Verne’s classic science fiction novel, since the volcanic entrance to the cavernous depths of the world in his story is ‘Snäfell,’ in western Iceland. For some , Journey to the Center of the Earth might be their only popular source of information on the country, since it is perceived as so remote, and, in many American minds at least, the Nordic countries can all get mixed up in a Scandinavian mélange of fjörds and vikings and skyr.

Snæfellsjökull, Iceland. Photo © Manny on BiteMyTrip.com

To Verne’s credit, therefore, he has put Iceland on the map for many people over the past century and a half (his book was first published in France in 1864, and was translated by 1871). To his discredit, however, he never visited Iceland himself, and instead relied primarily on two French works on Iceland written about scientific expeditions made there in the late 1830s. Continue reading

Icelandic Hell-broth

Krafla, Iceland. Photo © Land & Colors

In the Middle Ages, Iceland’s Mount Hekla was commonly thought of as a mouth of Hell, from whence one could hear the cries of the damned and even see their spirits haunting the peak — if the raging flames of hellfire weren’t blocking your view, that is. A few hundred years later, describing imagery as infernal or unearthly was still popular in travel accounts, as we saw in the case Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould’s thoughts on Námarskarð. Given the image above and those from the mud pits in the linked post, it really isn’t too surprising, especially after you consider that to reach these chthonic scenes the travelers had been riding ponies over a “tortuous and wretched” landscape of lava.

Iceland’s Fearful Agencies at Work

Over the summer, several people have asked me, after I tell them what I’m researching, whether the books I’m looking at are actually enjoyable to read or just another dry primary source, as dreary and monotonous as many travelers found Iceland’s vistas during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As with most things, the answer depends (largely on the book and certain chapters of each book), but for the most part I’ve flipped through hundreds of pages of travel literature with pleasure, not only because I know I’m being productive despite the beautiful day two floors above me outside Cornell’s Olin Library, but also because I find the Victorian British style of these authors–most of the works I’ve read so far were published between 1850 and 1880–quite engaging and fun to read.

Consider, for example, the following excerpts from Sabine Baring-Gould’s description of Námarskarð, an area full of hot mud springs in northern Iceland, in his 1863 book, Continue reading

Icelandic Cartography: Thoroddsen

This tiny thumbnail is all the American Geographical Society Library will let you download from their digital map collection, but if you click on the photo you’ll be routed to the University of Wisconsin’s Milwaukee Libraries Digital Collections page and have access to the map in stupendously high resolution, with the capability to zoom in and move around Þorvaldur* Thoroddsen’s 1901 Geological Map of Iceland; Surveyed in the years 1881-1898. This version was published in English at Copenhagen, but I have featured the 1906 version before, and keep a printed copy of the later publication (publ. Gotha, Germany), hanging in my room in Ithaca.

I use my copy for any quick reference I need to make while reading or thinking about places in Iceland for my research, and I also plan on starting to use little ball pins to mark down the most often-traveled areas and more quickly become accustomed with place-names and distances between locations. One interesting difference between the 1901 English and 1906 German versions of this map is the Vatna/Klofa Jökull region, which Continue reading

Icelandic Cartography: ca. 1875(?)

Although the paper documentation on this item give the date as 1860, when I looked at the map last week I noticed a discrepancy that made such a date of publication impossible. It’s all thanks to William Watts and his expeditions across the nice blank spot in the south-east corner of the island. When he crossed the Vatna Jökull, Watts helped add several landmarks to that white blotch (which, remember, was still in Gunnlaugsson and Ólsen’s 1849 “complete” map of Iceland) and Continue reading

Icelandic Cartography: 1849

Björn Gunnlaugsson was an Icelandic cartographer who along with the Danish army cartographer Ólafs Ólsen is credited with the first complete map of Iceland, even though the ever-present “Vatnajökull eða Klofajökull” space in the south-east was still blank. The Icelander received the Danish Order of the Dannebrog and the French Légion d’honneur for his surveying work, but the map was published under Ólsen’s name in Denmark, so future travelers would constantly refer to the “invaluable Olsen’s map” as essential to their expeditions around the country. Continue reading

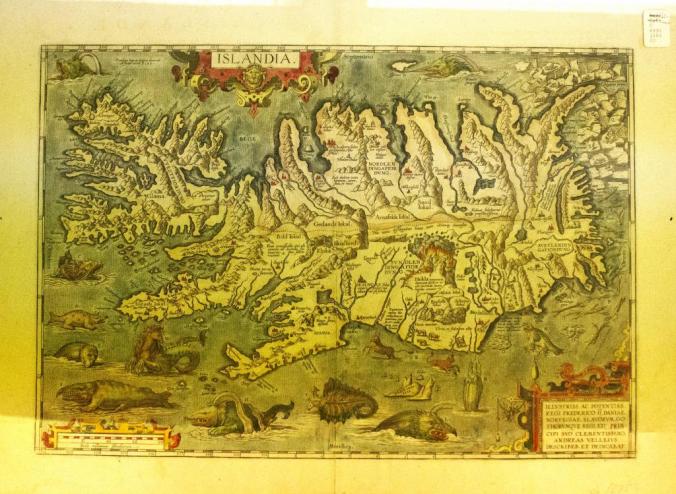

Icelandic Cartography: 1585

A 1585 copy of Islandia, by Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

One of my favorite things about the Rare & Manuscripts Collection in the basement of Cornell’s Kroch Library is that I can request to look at documents like this one, over four-hundred years old, and nobody comes and says, “Excuse me, but you’re a bit young to be doing that, aren’t you?” Granted, this old map was in a picture frame, so relatively speaking I wasn’t handling as preciously fragile a document as most of our other pieces from the 16th century are (the type that require white cloth gloves), but I still felt a lot of responsibility as I cautiously Continue reading

Sourcing Icelandic Wilderness

Þórsmörk. Glacier descending from Eyjafjallajökull. Collodion print by Frederick W. W. Howell ca 1900. Bequest of Daniel Willard Fiske; compilation by Halldór Hermannsson; Cornell University Library Rare & Manuscript Collections.

How Icelanders themselves saw the inner regions of their country, and the differences in perspective between the more and less educated segments of the population, can give valuable insight to the environmental practices of Iceland today, as well as portray the influence of European teaching on the more erudite Icelanders.

Although my focus is on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it will be useful for me to explore the roots of Icelandic and European thought on unused open land and Nature, especially since much of the rural Icelanders’ perceptions were tinted by folklore and legend. Therefore, at least a cursory background of Icelandic folklore as it relates to my research topic is necessary, so I will consult the multitude of translated Icelandic myths, folk stories, and sagas, as well as the vast literature on wilderness and Nature in European thought, that Cornell Library owns in its Icelandic collection. Continue reading

Icelandic Writings

The two first edition volumes of Captain Richard F. Burton’s “Ultima Thule; or, a Summer in Iceland,” 1875. Photo by Bauman Rare Books.

I’ve mentioned before that throughout the literature from the 18th and 19th centuries in Iceland I’ve found a conflict between traditional and modern conceptions of the land’s nature, but I want to clarify that this was likely not limited to a simple farmer-or-scientist dichotomy. My aim is to more closely examine any relationships between the writings of Icelanders and Europeans that were meant for a European audience (in the case of the former this involves contemporary translations) and tease out the nuances between them. I believe these scientists, travelers and explorers from various cultures sought the same thrill of setting foot on ground that had never been touched by “civilized” man before; they traveled untrodden lands whose exploration allowed them to feel a sense of discovery and lonely grandiosity while experiencing wilderness; and in some cases they desired the satisfaction of improving scientific knowledge of a natural area.

When I talk about looking at ‘writings’, I mean primary sources like Continue reading

The Love/Hate Relationships of Icelandic Steeds and Stockfish: Ichthyophagy

Reykjavík, Fish drying and shark oil station. Collodion print by Frederick Howell ca 1900. Bequest of Daniel Willard Fiske; compilation by Halldór Hermannsson; Cornell University Library Rare & Manuscript Collections.

Every account of travel in Iceland will cover the national meals in some fashion, but normally they are portrayed as quaint and disgusting. Many of the travelers of the period address the ‘unhealthy penchant for putrefied foods’ that revolved around stockfish. This included salmon and some other species but mostly meant cod, which was quite abundant in the oceans around the island. The fish would be cleaned and dried, and sometimes smoked, to provide food throughout the year, and the same applied for mutton. Dairy products from cattle, namely butter and cream, was often allowed to go rancid, much to the dismay of continental Europeans. Here is a paragraph I’ve translated from Jules-Joseph LeClercq, the Belgian who I referred to in my last post about Icelandic equitation, in his book Terre de Glace (1883):

I do not know how I can still respect those who are able to digest the horrible dishes to which my host introduced me, in particular dried shark-meat and whale fat. Overcoming my repugnance, I wanted to taste these incredibly novel delicacies, and was rewarded with an upset stomach for eight days. Continue reading

Hay Hiatus

I took this past weekend away from Cornell to help a friend with the hay harvest at a farm in rural NY where she works. Although I had been duly forewarned that haying is pretty hard and uncomfortable work, I had expected the bales to be relatively easy to lift and move around, and was wrong for a number of reasons.

First of all, the bales were pretty tightly packed. This meant that they were heavier than your average bale, and also put more pressure on the two pieces of twine that keep the flakes (segments of hay in a bale analogous to slices of bread in a loaf) compressed together. The twine, which unless you have a prodigious wingspan is the most efficient way to grab hold of the bales for throwing or carrying quickly, pinches your fingers against the bale when it is too tight, making it painful and difficult to get your hands on and off the bale. Add to these inconvenient factors the heat at the top of the barn and the need to crouch to avoid rafters and lightbulbs while carrying or tossing the bales (or, as I did, hit your head too often), Continue reading

Seasteading, Self-Reliance Utopia, And Our Shared Future

An article recently published in n+1 examines a utopian futurist form of an idea that seems oddly symmetric with Seth’s posts about the history of exploration using Iceland as a case study. Looking back, we see much in common with explorers, pioneers, pilgrims and adventurous thinkers of all sorts. Looking forward, we are inclined to embrace smart, creative, enthusiastic group efforts to resolve seemingly intractable challenges. Especially when they involve living on boats. We recommend reading the following all the way through:

To get to Ephemerisle, the floating festival of radical self-reliance, I left San Francisco in a rental car and drove east through Oakland, along the California Delta Highway, and onto Route 4. I passed windmill farms, trailer parks, and fields of produce dotted with multicolored Porta Potties. I took an accidental detour around Stockton, a municipality that would soon declare bankruptcy, citing generous public pensions as a main reason for its economic collapse. After rumbling along the gravely path, I reached the edge of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. The delta is one of the most dredged, dammed, and government subsidized bodies of water in the region. It’s estimated that it provides two-thirds of Californians with their water supply. Continue reading

The Love/Hate Relationships of Icelandic Steeds and Stockfish: Equitation

Ponies for export, Reykjavík. Collodion print by Frederick W. W. Howell. Bequest of Daniel Willard Fiske; compilation by Halldór Hermannsson; Cornell University Library Rare & Manuscript Collections.

Before jumping into the expeditions of William Watts into the Vatna Jökull (which, by the way, is pronounced /’jœ:kytl/ or “yokutl” as opposed to the “yokull” that most of us might expect), I thought I’d share some of the interesting and amusing impressions of British and French travelers regarding their encounters with the famous ponies and dried fish over and over again around the island.

This post will cover the horses and the next will examine the stockfish. There are a large number of images in the archival collections I am exploring this summer, and it would interesting enough just to share those and let them speak for themselves. But my task is to harvest history, so for now I will resist images and focus on ideas (sharing more images as the ideas take shape). Continue reading

Mapping Iceland

In my last post on the subject I mentioned that portions of Iceland on contemporary maps all the way up to the early 20th century remained blank. The main culprit for explorers, travelers, and cartographers was the great glacial region of Vatnajökull, at 3,139 sq. mi (8,130 sq. km) the largest glacier in Europe, and now a national park in southeast Iceland. Terrible snowstorms, heavy rains, unreliable ice, and poor local knowledge of the frigid plateau contributed to the failure of multiple expeditions by many men into the interior of the “Glacier of Rivers,” and during the late 1800s it became clear that there was frequent volcanic activity in the area as well.

1906 geological map by Icelandic geographer/geologist Þorvaldur Thoroddsen, who is credited with being the first to map the interior of the Icelandic Highlands in 1901, which is when this map was first published. The different colors represent different compositions of the island, such as basalt, liparite, volcanic ash, etc.