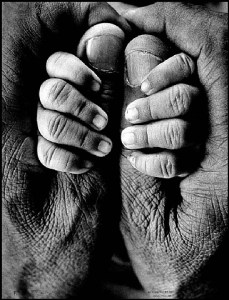

These African Grey parrots were rescued from smugglers and released on Ngamba Island in Lake Victoria. The African Grey parrot is the single most heavily traded wild bird. PHOTO: CHARLES BERGMAN

In all that we write about conservation, a related tag – unfortunately – happens to be extinction. Brought about by forest loss, miscalculated development plans, social and political apathy towards ecosystems, lack of awareness – the reasons we’ve all heard of. Now, National Geographic reports on the disappearance of the ‘talking bird’:

Flocks of chattering African Grey parrots, more than a thousand flashes of red and white on grey at a time, were a common site in the deep forests of Ghana in the 1990s. But a 2016 study published in the journal Ibis reveals that these birds, in high demand around the world as pets, and once abundant in forests all over West and central Africa, have almost disappeared from Ghana. Uncannily good at mimicking human speech, the African Grey (and the similar but lesser-known Timneh parrot) is a prized companion in homes around the world. Research has shown that greys are as smart as a two-five year-old human child—capable of developing a limited vocabulary and even forming simple sentences.