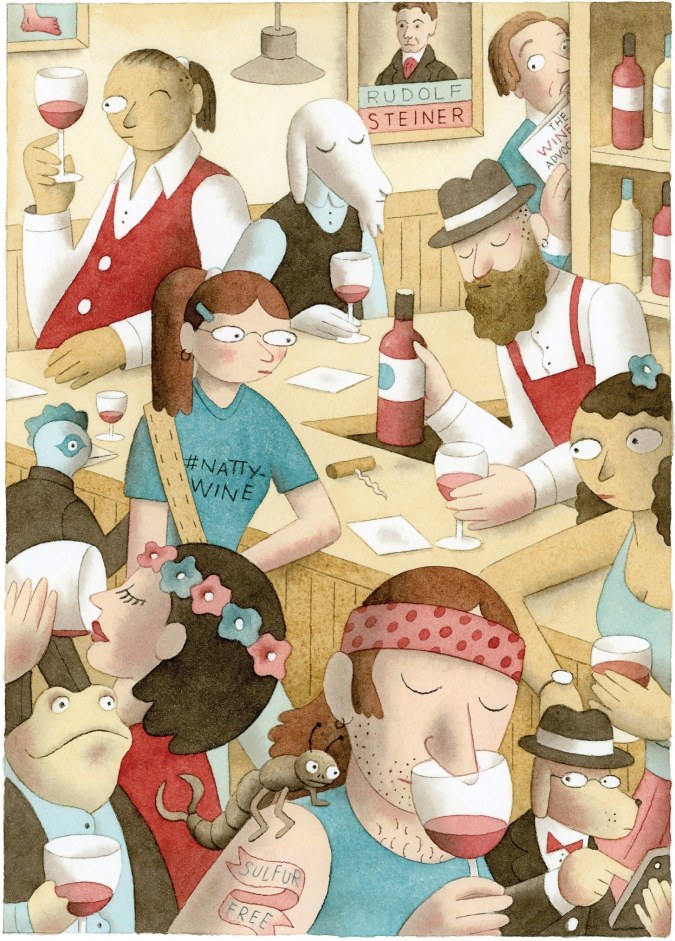

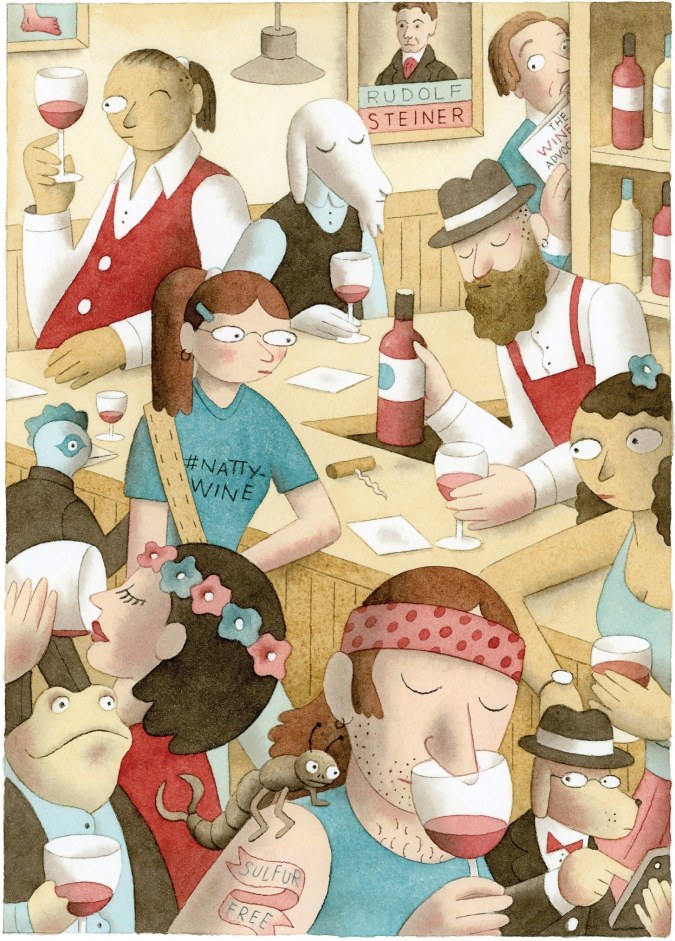

Winemaking methods that once seemed suspect now look like authenticity. Illustration by Greg Clarke

What does good taste like? Perhaps goodness is the better word to use in that question, because the question is not about what good taste is, as in how we determine when something is tasteful. This article, using wine as a prop, offers a way to think about goodness, in the virtue sense, and what it might taste like, without simply rehashing the tiresome complaints about virtue signaling. The author had me at the title, because it touches on themes we have been thinking about lately; then the mention of working of Mendoza, where I worked in 2007, ensured I would read on. In the second paragraph seeing Itata, a region that was part of my workplace 2008-2010, I was triply hooked:

The mainstreaming of natural wines has brought niche winemakers capital and celebrity, as well as questions about their personalities and politics.

In 2010, Dani Rozman had just graduated from the University of Wisconsin. He was so deliberate and thoughtful that his friends claimed it was inevitable that he’d end up a history professor with a closet full of cardigans. But Rozman went to Argentina instead, and wound up in Mendoza, the hub of the country’s wine scene, working at a startup that helped wealthy people realize their wine dreams—you could buy a vineyard from afar, have someone else farm it, design the labels, and receive cases of “your” wine to show off at dinner parties.

One summer, Rozman went to Itata, at the southern tip of Chile’s wine-producing region, to work the grape harvest at a local winery. He had the impression that winemakers were like the clean-cut guys in Napa with family money and fleece vests. Itata was different. The winery was just a shipping container and a mesh tent, and the work was non-stop. Rozman had grown up in a health-conscious family that nonetheless “had to be reminded that food was farmed,” he said; being in daily contact with plants felt revelatory. Some of the vines had been planted centuries earlier, by conquistadores and missionaries. The grapes were País, a varietal that had fallen out of favor as winemakers turned to popular ones like Cabernet Sauvignon. The methods were traditional, too—the fruit was picked by hand, destemmed with a bamboo implement called a zaranda, then fermented in clay pots. The finished product was startling, in a good way. “At that time in Argentina, Malbec was king,” Rozman told me. The country made lots of homogeneous, high-alcohol wines aged in oak barrels, catering to international appetites—“the French-consultant thing,” as Rozman put it. To him, they tasted heavy and expressionless, while the Itata wines were stripped down and elemental. “It was like night and day,” he said. Continue reading →