Split by the Isthmus of Panama: Species of butterfly fish, sand dollar and cone snail that today live on the Pacific and Caribbean coasts of Central America are very closely related. Genetic sequencing shows that only 4 to 3 million years ago, each pair was a single species, demonstrating that marine connections between the oceans must have existed until that time. (Image by Coppard et al., via The Smithsonian)

It’s probably not something you’ve given much thought to, unless perhaps you’ve visited Central America in the past and experienced first-hand the incredible biodiversity displayed in such a small area. Part of the reason why this little strip of land has so many different species of animals and plants is that it connects two very large continents that used to be separate, but it also has given birth to new aquatic species via evolution, as you can see from the image above. Previous thought on the topic had been that the Isthmus of Panama rose from the ocean roughly between 23 and 15 million years ago, but a very large and very interdisciplinary team of researchers – mostly with some link to the Smithsonian Institution, which has its Tropical Research Institute in Panama City – have reaffirmed that the enormously important geological change occurred around 3 million years ago.

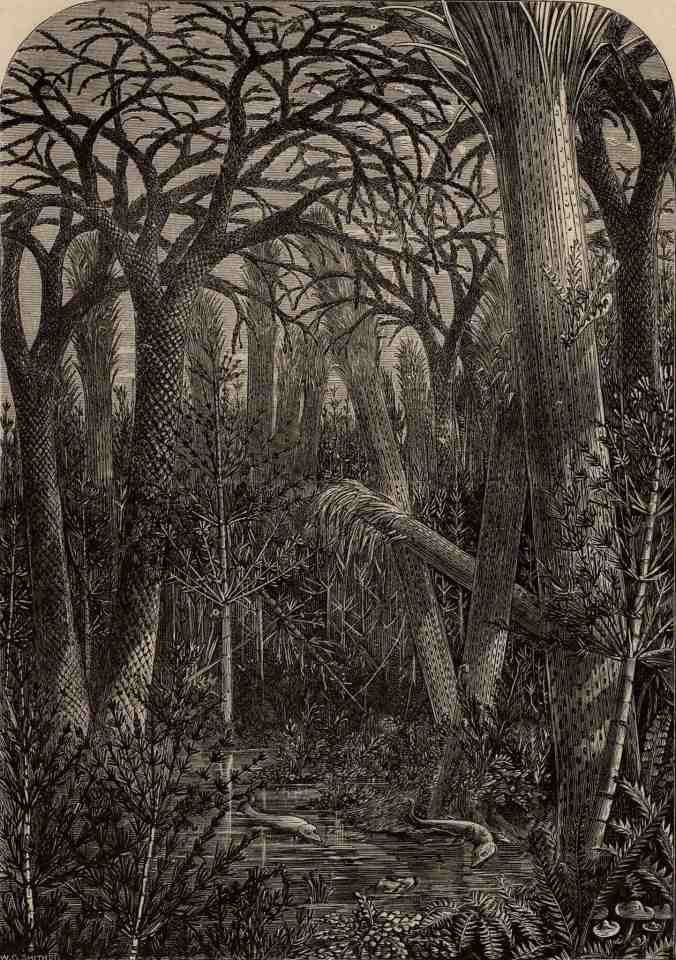

“The Invention of Nature” reveals the extraordinary life of the visionary German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) and how he created the way we understand nature today. Though almost forgotten today, his name lingers everywhere from the Humboldt Current to the Humboldt penguin. Humboldt was an intrepid explorer and the most famous scientist of his age. His restless life was packed with adventure and discovery, whether climbing the highest volcanoes in the world, paddling down the Orinoco or racing through anthrax–infested Siberia. Perceiving nature as an interconnected global force, Humboldt discovered similarities between climate zones across the world and predicted

“The Invention of Nature” reveals the extraordinary life of the visionary German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) and how he created the way we understand nature today. Though almost forgotten today, his name lingers everywhere from the Humboldt Current to the Humboldt penguin. Humboldt was an intrepid explorer and the most famous scientist of his age. His restless life was packed with adventure and discovery, whether climbing the highest volcanoes in the world, paddling down the Orinoco or racing through anthrax–infested Siberia. Perceiving nature as an interconnected global force, Humboldt discovered similarities between climate zones across the world and predicted