“You shouldn’t be out there filling potholes at your age.” That’s what Venkateswari Katnam tells her 67-year-old husband, Gandgadhara. He doesn’t listen. Over the past five years, he estimates that he has filled around 1,100 potholes on the streets of Hyderabad. He carries bags of gravel and tar in the trunk of his Fiat, along with a spade, two brooms, a wire brush and a crowbar. When he spies a pothole — or learns of one from a Facebook message — he can usually fill it in under an hour. He clears out any debris or standing water, pours in the mix of gravel and tar, levels it off and waits about 30 minutes for it to set. He puts up red flags in English, Hindi and Telugu to make sure no one steps or drives in it. And when he’s done, he takes a selfie to add to his collection of filled pothole Continue reading

India

From India to Houston, the 40-year-old Yogurt

A recent batch of Veena Mehra’s yogurt in Houston. She’s been making yogurt the same way, with the same starter, for about 40 years. PHOTO: Nishta Mehra

If you’re making your own yogurt at home, you need an old batch to make a new batch. And the community of microbes in that yogurt starter — and the flavor — should remain relatively unchanged if you make it the same way every time. That’s what Rachel Dutton, an assistant professor of microbiology at the University of California, San Diego who studies cheese and other dairy products, says, anyway.

A Brick to Breathe Easy?

India’s brick industry, spread out over 100,000 kilns and producing up to 2 billion bricks a year, is a big source of pollution. To fire to hot temperatures, the kilns use huge amounts of coal and diesel, and the residue is horrendous: thick particulate matter, poor working conditions, and lots of climate-changing emissions. MIT students have created an alternative. The Eco BLAC brick requires no firing at all and makes use of waste boiler ash that otherwise clogs up landfills.

Travel Made Easy Through Air

No, we are not talking flying here. But the Curvo, the world’s first non-linear aerial ropeway for second tier urban commutation. Pollution and traffic-free, the service, operational on electricity, would be on steel frames spreading at a distance of around 90-100 m running through the existing arterial and other roads to avoid congested streets of the city. There will be elevated stops at every distance of 750 m and the cars would be able to gain speed of about 4.25 m per second (12.5 km/hour) with the ability to carry an estimated 2,000 people every hour. Curvo is expected to be introduced in 18-24 months. The cabins will have an accommodation capacity of 8-10 persons.

The Ice Man of India

Ladakh’s beautiful mountains might be a paradise for tourists, but ask the locals who struggle to meet their basic water needs every year. PHOTO: Wikimedia Commons

Rain is scarce in the snow-peaked Himalayas of northern India, and summers bring dust storms that whip across craggy brown slopes and sun-chapped faces. Glaciers are the sole source of fresh water for the Buddhist farmers who make up more than 70% of the population in this rugged range between Pakistan and China. But rising temperatures have seen the icy snow retreat by dozens of feet each year. To find evidence of global warming, the farmers simply have to glance up from their fields and see the rising patches of brown where, once, all was white. Knowing no alternative, they pray harder for rain and snow. But Chewang Norphel had the answer: artificial glaciers.

For the Love of Rains and Traditions

Celebrated in June every year, San Joao is one of Goa’s cultural festivals. Tradition has it that it was on this day that unborn St. John the Baptist ‘leapt with joy’ in his mother Elizabeth’s womb, as Mary, the mother of Jesus visited her. PHOTO: Harsha Vadlamani

Yes, this is yet another rain-inspired story, after the one on Communist reading rooms. But such is the power of the Indian monsoon, that it can sway even the most stoic of minds. For comparison, the feelings and emotions associated with the deluge mirror those of when sighting the first of the cherry blossoms or even the Northern Lights. May be less, may be more. Any how, this post is about a fun tradition that has its roots in the picturesque villages of Goa, a popular tourist destination. And the feast of Sao Joao is a playful mix of religion, tradition, lots of merrymaking, and jumping into wells. Yes, wells. And oh, the event marks the six-month countdown to Christmas!

Mind Your Language

As global trade expanded through European conquests of the East Indies, the flow of Indian words into English gathered momentum. PHOTO: EDL

Recently, we discussed Indian classical music as a ground of collaborations and exchanges. Cultural hegemony aside, we’d rooted for the European violin which is a mainstay at temple concerts and for the clarinet and trombone, which we may be lucky to see in music arrangements. Today, it’s about language. About how India gave the world worlds including pundit, jungle, nirvana, and more.

“Ginger, pepper and indigo entered English via ancient routes: they reflect the early Greek and Roman trade with India and come through Greek and Latin into English,” says Kate Teltscher. “Ginger comes from Malayalam in Kerala, travels through Greek and Latin into Old French and Old English, and then the word and plant become a global commodity. In the 15th Century, it’s introduced into the Caribbean and Africa and it grows, so the word, the plant and the spice spread across the world.” “The Portuguese conquest of Goa dates back to the 16th Century, and mango, and curry, both come to us via Portuguese – mango began as ‘mangai’ in Malayalam and Tamil, entered Portuguese as ‘manga’ and then English with an ‘o’ ending,” she says.

Of Rains and Communist Reading Rooms

Monsoon rains in Kerala – the greatest drama I’ve ever watched. They tick everything on Aristotle’s checklist for a good play. A country dried by summer and hoping on a good ending makes for a decent plot. Meet the characters. A thick blanket of menacing grey, humid air hugging skin. Gusty winds that uproot trees and power lines, darkness that comes calling even before night. And the stellar spectacle of a finale – prayers, predictions, and calculations answered in silvery drops. Stunning, stinging, and relieving all at once.

Writing this while watching blue and grey jostle in the skies, the earth still smelling of the last rain (petrichor is the word), I am reminded of the book I’m reading now. One that is as old as me, one befitting the best season in India. Alexander Frater’s Chasing the Monsoon.

“As a romantic ideal, turbulent, impoverished India could still weave its spell, and the key to it all – the colours, the moods, the scents, the subtle, mysterious light, the poetry, the heightened expectations, the kind of beauty that made your heart miss a beat – well, that remained the monsoon.”

― Alexander Frater, Chasing the Monsoon

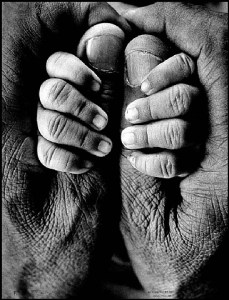

A Picture Perfect World

When is the last time you saw someone sans a camera? No device in their hands and none dangling around their necks? Well, “we can’t seem to recollect” is our answer, too. And, may be there are reasons for it. More than the power to immortalize fragments of time, a photograph brings together all the pictures you’ve seen, the books you’ve read, the music you’e heard, the people you’ve loved. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt, say others. And ace Indian photographer, Raghu Rai, protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson, pens his own take in Nat Geo Traveler.

I am called a photographer, and my dharma is photography but I think of myself as an explorer. To me, the best way to explore life is through photography. Life changes constantly, so the more you explore the more you are enriched.

Indian Music, European Violin

Clarinet, mandolin, saxophone – the Carnatic tradition of Indian classical music is a ground of growing collaborations across the world. PHOTO: Aambal

Indian classical music has our attention today. Thanks to its fluidity and pliability that makes it a thriving collaborative space. If you want the history of this art form, find it here. And for crossovers of Western strains and Indian sensibilities, head here. For much of Indian cultural evolution and practice, music is not a standalone art form. It forms the crux of cultural discourse, an important part of the axis that binds community, ritual, practice and social mores. The Carnatic music form of South India is a rather interesting and rich tradition among the musical traditions of the world. For one, it is tremendously alive and vibrant, not just in South India but also in different ways around the world.

Interestingly, the Carnatic form has also been receptive to a great number of innovations, especially in the sorts of instruments it has drawn into its fold. The European violin, for instance, finds an entry as late as the 19th century but has become near irreplaceable in the Carnatic context and performance formats of today. Tipped as being the one instrument that is as close as possible to the infinite flexibilities of the human voice, the violin has spawned different playing styles and traditions of its own in its comparatively brief but highly impactful history.

Putting the Horse Before the Cart

For better or worse – the Indian city of Mumbai is preparing to bid goodbye to one of its icons. The city’s ornate horse-drawn carriages are nearing the end of the road after a court in the Indian city ruled them illegal. The silver-colored Victorias – styled on open carriages used during Queen Victoria’s reign – have been plying Mumbai’s streets since British colonial times, and for years have been a tourist attraction. But recently, the Bombay High Court agreed with animal welfare groups, who had petitioned for a ban citing poor treatment of the horses, that the practice was cruel.

Yoga – Popular and Partisan in Nature?

India celebrates its first International Yoga Day today. PHOTO: Members of the Navy performing Yoga at sea.

On Sunday morning, the Indian capital New Delhi’s broadest and grandest avenue, Rajpath, will be covered in a sea of yoga mats, with some 35,000 people expected to indulge in mass physical contortions to mark the first International Day of Yoga—a pet initiative of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He pitched the idea to the U.N. General Assembly (UNGA) in his maiden speech at the annual diplomatic confab in September. A formal UNGA resolution to establish an international yoga day was passed in December, with more than 170 countries co-sponsoring the move. Modi’s government has since gone all out to promote the first yoga day, calling its diplomatic corps into service to plan events in more than 190 countries.

The Modi government is attempting to set two world records, including the largest yoga lesson (the current record was set in India in 2005, when nearly 30,000 students from more than 360 schools participated in a yoga session in the central Indian city of Gwalior). It also wants to set a record for the number of nationalities involved in a single yoga lesson, a category it hopes to pioneer.

Six Yards of Handwoven History

An understated tourist destination, Chanderi and its looms are often missed on the route to nearby Orchha and Khajuraho. PHOTO: Gaatha

You must have heard of India’s ubiquitous piece of clothing that is the sari. Graceful, flattering, stately – several are the adjectives used to describe this six yards of fabric. But have you heard its story? From the threads and to the loom, to the people striving to uphold the dignity of working by hand and keeping the powerloom lobbies at bay? Then, the story of the Chanderi sari is for you to read, courtesy the Outlook:

The softly shimmering legacy of many hands lingers in its weave, the gorgeous rustle of cotton and silk hails its arrival: the handloom sari, timeless showcase of India’s heritage textile, gathered from all over the country to drape the Indian woman. From Delhi living room conversation piece to subtle South Indian wedding showstopper, the handloom sari has always kept standards high. Parrot green, frighteningly pink, marvellously magenta, from Kancheepuram in Tamil Nadu to Sambalpuri in Orissa, it wends its way into trousseaus, staple sari collections and 100 Sari Pacts (the most recent trend in sari preservation has women vowing to wear a hundred saris and commemorate the traditional garment). Its weavers are craftsmen, their outlines blurred by the sheer number of people involved in the creation of one long, winding stretch of cloth.

The ‘E’ word – E-waste

The StEP Initiative forecasts that by 2017, the world will produce about 33 percent more e-waste, or 72 million tons (65 million metric tons). That amount weighs about 11 times as much as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

By 2017, the global volume of discarded refrigerators, TVs, cellphones, computers, monitors and other electronic waste will weigh almost as much as 200 Empire State Buildings, a new report predicts.The forecast, based on data gathered by United Nations organizations, governments, and non-government and science organizations in a partnership known as the “Solving the E-Waste Problem (StEP) Initiative,” predicts e-waste generation will swell by a third in the next five years, led by the United States and China. The StEP Initiative created a map of the world’s e-waste, which is available online. [Infographic: Tracking the World’s E-Waste]

10,000 km in a Tuk-tuk and With the Sun

Tejas is a renovated Piaggio Ape with a 13-kilo-watt prototype engine, lithium-ion batteries and six solar panels. PHOTO: IBN

Our itinerary has been filled with travel all week. And we almost gave The New Indian Express article on the travel plans of Indian engineer Naveen Rabelli and Austrian filmmaker Raoul Kopacka a miss. That was only until we read the details: a 10,000 km journey from India to London on a self-built solar-powered tuk-tuk/autorickshaw to Britain to promote a sustainable low-cost alternative-transport solution and check air pollution in towns and cities across their journey. Talk about going the extra mile.

A Garden of Waste

Successful stories of upcycling, recycling and effective waste management are heartwarming to say the least. Because they speak of someone thinking about the future and taking the time and effort to act on a lay thought. That’s what the world (and the environment) needs – time. And, Nek Chand, who was born in Pakistan but made India his home, gave almost 60 years of his life to make trash beautiful, to give it meaning and purpose. He created a garden of sculptures and waterfalls out of trash over 40 acres and managed to hide it from everybody for 18 years. It was his secret to keep and is now Chandigarh’s pride. The nation’s, too.

In his spare time, Chand began collecting materials from demolition sites around the city. He recycled these materials into his own vision of the divine kingdom of Sukrani, choosing a gorge in a forest near Sukhna Lake for his work. The gorge had been designated as a land conservancy, a forest buffer established in 1902 and nothing could be built on it. Chand’s work was illegal, but he was able to hide it for eighteen years before it was discovered by the authorities in 1975. By this time, it had grown into a 12-acre (49,000 m2) complex of interlinked courtyards, each filled with hundreds of pottery-covered concrete sculptures of dancers, musicians, and animals.

When Nature is the Weatherman

Its monsoon delayed and weakened by a cyclonic storm and the El Nino, India is bracing for tough days ahead. PHOTO: Madhyamam

All through the last weeks of May and the first days of June, most Indians have been looking to the skies. For answers and signs of the monsoon rains. With India being a predominantly agrarian country, the rains decide whether the country grows enough to feed its 1.25 billion people or relies on imports to satiate hunger and demand. And last evening, we saw the first signs of a healthy monsoon, amid fears of the rains being a poor show this year.

Women of Their Worlds

In the small hilly Indian state of Meghalaya, a matrilineal system operates – but some men are campaigning for change PHOTO: Karolin Kruppel

What does the north-eastern Indian state of Meghalaya and a valley on the border of Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China have in common? They are home to a couple of the handful matrilineal communities that still exist. In an age where most important offices of power are held by men, it is critical to evaluate how these communities hold on to a way of life unchanged for thousands of years. Not to forget the challenges they face in continuing to look at women as the driving force and the soul of their existence.

Where Does This Light Come From?

Energy from solar, biomass and hydrogen is coming together for the first time in India to light up a tribal hamlet. PHOTO: The Telegraph

When India’s Rabindranath Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, he made headlines. He continued to be in the news when he decided to use the prize money to set up a university town in India. Today, Santiniketan and its Visva-Bharati University can stake claim to their unique set of trailblazers of alumni; Nobel winning economist Amartya Sen and ace Indian auteur Satyajit Ray are among them. While the light of education draws thousands to the gates of the university town, its hinterland remains in darkness. But in education that leads to innovation we trust and there seems to be a glimmer of a sustainable solution on the horizon.

Meet the ‘Water Man’ of India

The 2015 Stockholm Water Prize has been awarded to Rajendra Singh for his consistent attempts to improve the country’s water security PHOTO: SIWI

Twenty years ago, when 28-year-old Rajendra Singh arrived in an arid village in Rajasthan, he came with degrees in Ayurveda and Hindi and a plan to set up clinics. That’s when he was told the greatest need was not medical help but clean drinking water. Groundwater had been sucked dry by farmers, and as water disappeared, crops failed, rivers, forests and wildlife disappeared and people left for the towns. In 2008, The Guardian listed him as one of its “50 people who could save the planet”. In March 2015, he was awarded the Stockholm Water Prize, known as the Nobel Prize for water.