Krulwich is our go-to guy on a certain kind of day. A day when important scientific ideas might otherwise put us to sleep, and just need a fresh approach to get our attention. Today is one of those days, and the pied piper of fun science delivers a short and sweet one:

Continue reading

Science

Conservation Literacy

We’ve mentioned how an interpretive guide can bring the rainforest to life before. We’ve even touched on the fact that sometimes the best of those guides have “poacher” on their resumés, which follows a similar logic to the observation that often the most devoted practitioners of a religion are the newly converted. Here I’d like to point out a recent study by researchers from Wageningen University, along with Kenyan and British colleagues, published in a recent article in the journal Biological Conservation that correlates the levels of literacy and education with general conservation and the long-term protection of local wildlife.

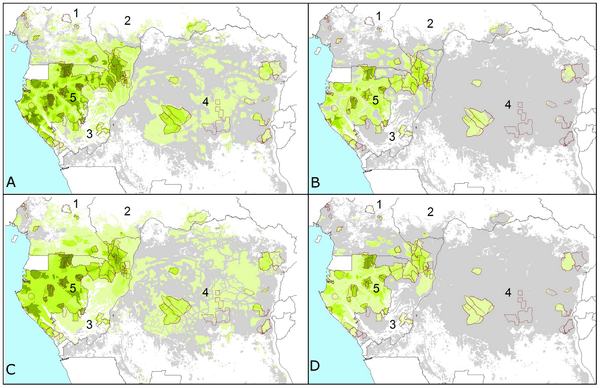

The team of ecologists evaluated the number of elephants across Africa’s continental range, irrespective of political boundaries. The analysis included the numbers of individual elephants and determined the relation with 19 ecological variables, including rainfall, forage and water availability, and 15 human variables, including human density, welfare, literacy rate, and habitat fragmentation.

Although environmental factors such as the availability of food and water were obviously important, it appears that human factors—including policies, corruption, or the country’s economy—are even more important than environmental factors.

The authors write that:

…even for such charismatic species as the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)…we show through continent-scale analysis that ecological factors, such as food availability, are correlated with the presence of elephants, but human factors are better predictors of elephant population densities where elephants are present. These densities strongly correlate with conservation policy, literacy rate, corruption and economic welfare, and associate less with the availability of food or water for these animals. Continue reading

The Poetry of Science

This conversation between two luminaries of modern science: Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist and host of NOVA and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins is as poetic as it is informative, and well worth the time it takes to listen.

Professor Dawkins says that science is the poetry of reality. We take pleasure in his and Professor Tyson’s expanded bandwidth… Continue reading

Read, Weep, Act

A just-released scientific study documents the destruction. Roughly 25,000 elephants per year are killed in Africa to feed the demand for ivory in Asia, and the pace has increased in the last decade such that, in another decade, extinction is possible. A petition that led to one important-sounding announcement provided momentary hope until it was noted that no dates or even vague timelines were committed to. For now, we have only the clear, cold facts of science and whatever stimulus these findings provide for us to take action:

Abstract

African forest elephants– taxonomically and functionally unique–are being poached at accelerating rates, but we lack range-wide information on the repercussions. Analysis of the largest survey dataset ever assembled for forest elephants (80 foot-surveys; covering 13,000 km; 91,600 person-days of fieldwork) revealed that population size declined by ca. 62% between 2002–2011 Continue reading

Camera Traps, Unite

Sharing technology, data, knowhow. Pooling resources in the common interest across regions of the tropical world for the sake of biodiversity conservation. Take a look at what TEAM is doing. A six minute video appears on the Guardian‘s website, providing much-appreciated coverage:

One million images of wildlife in 16 tropical forests around the world have been captured by the Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring (TEAM) Network. Since it began its work in 2008 to monitor changes in wildlife, vegetation and climate, cameras in the the Americas, Africa and Asia have photographed more than 370 different species including elephants, gorillas, chimpanzees, large cats, honey badgers, tapirs and tropical birds Continue reading

Katrina, Come To Kerala!

Thanks to this book review in the New York Times we see Katrina in a light similar to that of several other remarkable people we have strongly urged to visit our neck of the woods. Katrina’s work is illustrated above and in these images from her website.

From the description of her new book we would find some of this work challenging (as anatomical renderings can sometimes be), but from an artistic, craft/technical and scientific point of view, phenomenal:

There is more to a bird than simply feathers. And just because birds evolved from a single flying ancestor, doesn’t mean they are structurally all the same. With over 300 stunning drawings representing 200 species, The Unfeathered Bird is the most richly illustrated book on bird anatomy ever produced and offers a refreshingly original insight into what goes on beneath the surface. Continue reading

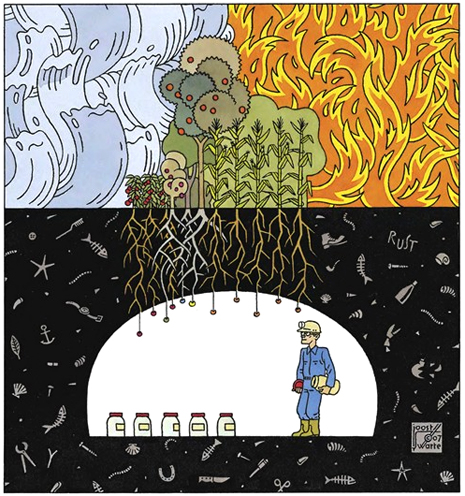

Coffee Rust

Several contributors to this blog live(d) and work(ed) in Central America and know exactly what you mean. Those of us based in south India–where there is high quality arabica growing in the Coorg-Chikmagalur corridor–are hopeful that this “rust” is contained quickly. So, Dear John, please succeed:

Until this year, John Vandermeer, an ecologist and coffee researcher at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, had never lost a tree to fungus. Continue reading

More On Internal Compasses

More and more stories addressing the understanding scientists are developing about internal guidance systems:

Every summer, millions of sockeye salmon flood into the Fraser River in British Columbia, clogging its shivering waters with their brilliant blushing bodies.

Scientists and spectators alike have long been awed by the sockeye’s audacious struggle to swim upstream to spawn. And while it has been known for years that a salmon can smell its way up the river to find its natal stream, no one has been able to explain just how these beautiful and economically vital fish find their way back from the open ocean, 4,000 or 5,000 miles away, to the right river mouth. Continue reading

Plant Physics

Another in the excellent series of Cornell luminaries sharing their work in informal presentations (i.e. “in the stacks”) for lay folk like us. Click the image to the right to go to the video of this talk:

Over 90 percent of all visible living matter is plant life. Plants clean the air, provide food and fuel, fibers for clothing, and pharmaceuticals. Interweaving themes that emphasize biology and physics, the book explains how plants cannot be fully understood without examining how physical forces and processes influence growth, development, reproduction, evolution, and the environment. Continue reading

Teacher Of Teachers In Natural History

Because of its importance to this idea we work with, entrepreneurial conservation, we pay attention to the history of natural sciences. We are curious, as individuals and collectively, about how we found our way here. In the Books sections of the New York Times Rebecca Scott reviews the Christoph Irmscher study on the Swiss immigrant scientist Louis Agassiz and his contributions to science–and therefore nature and conservation–in his adoptive country:

Nonetheless, there is no arguing with the claim that Agassiz, a Swiss immigrant, was pivotal to the making of American science. He was “one of the first,” Irmscher writes, “to establish science as a collective enterprise.” He was extraordinarily prolific and influential in many fields, including paleontology, zoology, geology and glaciology. Continue reading

Another Look At Sight

(Copyright: Thinkstock). Our eyes are remarkable in making almost instant sense of the world around us in ways that even the most sophisticated machines can’t do. So what cues do we pick up that make sure we can see the wood for the trees?

The BBC provides this interesting view on the relationship between sight and other forms of sense:

One of the unforeseen boons of research on artificial intelligence is that it has revealed much about our own intelligence. Some aspects of human perception and thought can be mimicked easily, indeed vastly surpassed, by machines, while others are extremely hard to reproduce. Take visual processing. We can give a satellite an artificial eye that can photograph your backyard from space, but making machines that can interpret what they “see” is still very challenging. Continue reading

Science Scores One For The Bees

Environmental campaigners say the conclusion, by Europe’s leading food safety authority, sounds the “death knell” for the insect nerve agent neonicotinoid. Photograph: Alamy

There is a steady stream of unhappy news for bees in recent years, with scientists often being called to study the problem and propose solutions; today was just another such news day. We have a particularly soft spot for bees, so these actions taken, reported from Europe, are welcome additions to today’s news:

…”This is a major turning point in the battle to save our bees,” said Friends of the Earth’s Andrew Pendleton: “EFSA have sounded the death knell for one of the chemicals most frequently linked to bee decline and cast serious doubt over the safety of the whole neonicotinoid family. Ministers must wake up to the fact that these chemicals come with an enormous sting in the tail by immediately suspending the use of these pesticides.” Continue reading

Questions Science Forces Us To Consider

Michael Specter has written on more than one occasion on topics that are of concern to any environmentally sensitive reader, but with an unexpected twist. Not unexpected in a “denier” sense, nor in the typical skeptic‘s perspective. A few months back he wrote a blog post on GMOs that caught our attention for its simple explanation of a piece of legislation, and then surprised us with the notion that the proponents of that legislation (including a food writer we point to frequently) might have it all wrong. Here is another:

It has been more than fifteen years since companies like Monsanto began intense efforts to export agricultural biotechnology from the United States to the fields of Europe and the United Kingdom. The battle continues to this day. Few opponents have been more militant or effective than Mark Lynas, one of the first people to break into fields that scientists had planted with genetically modified test crops—and then rip them out of the ground. Continue reading

Newly Discovered Species

A bit of synchronicity accompanies this post, following Seth’s post about Quagmire, and the post just prior to that about our efforts to balance out doom and gloom with as much evidence as we can find of “how to” or “there is still time and it is worth making the effort” stories.

Case in point: while Seth’s book review covers a certain delta in a certain country at a certain moment in history–all with pretty challenging consequences environmentally–the Guardian had just posted a sampling of 12 images of the 126 species of animal and plant life newly identified by biologists working in the same region in the last year or so. Those came from a new publication of WWF, whose press release we quote here:

126 new species have been discovered in the Greater Mekong in the past year. The total newly identified by scientists in 2011 includes 82 plants, 21 reptiles, 13 fish, 5 amphibians, and 5 mammals.

Profile Of Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award-Winner

Click the image above to go to another note of tribute, this one in the current Atlantic, for a remarkable leader in academia, this one at the beginning of her career:

Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute, a genomics research center affiliated with MIT and Harvard, has known Sabeti since the late 1990s, when she was an undergraduate advisee at MIT. Continue reading

Sometimes Science Says Otherwise

Among family, friends and colleagues everyone knows someone who has tried to kick the habit. Many succeed. Once the habit is kicked, where does it go? And for those who have not kicked the habit, and are still flicking the remainders about, where do those go? Apparently, both end up in bird land, and for reasons we might find acceptable:

We never actually established why birds suddenly appear every time you are near. It might just be because you are one of the terrible, horrible people who throws cigarette butts on the ground everywhere. When a little bird waddles out and picks one up and uses it to build a nest, though, you are sort of redeemed, in that the world becomes a better place for its bird family.

Research published today in the journal Biology Letters followed urban birds and measured the amount of cellulose acetate (from cigarette filters) in their nests. The nests with more butts had fewer parasites. Continue reading

Zombie Architecture & Rainforest Creatures

In the New York Times, the great science-explaining journalist Carl Zimmer writes about a mystery most of us would never otherwise encounter:

In the rain forests of Costa Rica lives Anelosimus octavius, a species of spider that sometimes displays a strange and ghoulish habit.

From time to time these spiders abandon their own web and build a radically different one, a home not for the spider but for a parasitic wasp that has been living inside it. Then the spider dies — a zombie architect, its brain hijacked by its parasitic invader — and out of its body crawls the wasp’s larva, which has been growing inside it all this time. Continue reading

Byron’s Daughter, Randomness And A Great Science Writer

The Royal Society’s recognition is enough to make even the author blush (in the video above, just barely visible in the fifth minute):

From the invention of scripts and alphabets to our current world of blogs and tweets, James Gleick tells the story of information technologies that changed the very nature of human consciousness. ‘The Information’ is the story of how we got here and where we are heading.

Professor Jocelyn Bell Burnell DBE FRS, Chair of the judges, said: “The Information is an ambitious and insightful book that takes us, with verve and fizz, on a journey from African drums to computers, throwing in generous helpings of evidence and examples along the way. It is one of those very rare books that provide a completely new framework for understanding the world around us. It was a privilege to read.”

James Gleick said: “This is a very unexpected surprise. I am not a scientist, but I have my nose pressed against the glass. I visited the Royal Society 12 years ago to research a biography of Isaac Newton. It is a pleasure to be back again.”

A Fountain Of Ideas, Spouting In Many Directions

The screen shot to the right shows the simplicity of the site. Which otherwise is an explosion of ideas, observations written with craft, and links. We wonder just about every day how she does it. And why. But that is on a need to know basis so we have just continued to visit her site and admired her prolific sharing. In a profile over the weekend, we learn a bit about how and why she has the stuff:

SHE is the mastermind of one of the faster growing literary empires on the Internet, yet she is virtually unknown. She is the champion of old-fashioned ideas, yet she is only 28 years old. She is a fierce defender of books, yet she insists she will never write one herself. Continue reading

Brute Force Technology

In my last book review sourced from the course I’m taking on environmental history, I hinted that some of the authors we read were very keen to list our failures of the past and quantify the damage we’ve done. Paul R. Josephson, in his Industrialized Nature, does just this, seeking to demonstrate how large-scale resource management systems almost always ensure environmental degradation and long-term losses in different ways. Dubbing these systems “brute force technologies,” Josephson studies how they were employed by varied combinations of diverse political systems, social groups, and economic goals on different types of raw materials in several countries. All led to similarly disastrous results for the ecosystems in question, but, the author argues, man’s hubris is strong enough to convince political and scientific spheres that further innovation can solve problems and maintain profitable advances in the future. While describing the ecological damage caused by brute force technologies, Josephson makes sure to include social stresses inflicted upon local communities, such as native tribes and other underrepresented groups directly affected by the overwhelmingly negative changes.

In my last book review sourced from the course I’m taking on environmental history, I hinted that some of the authors we read were very keen to list our failures of the past and quantify the damage we’ve done. Paul R. Josephson, in his Industrialized Nature, does just this, seeking to demonstrate how large-scale resource management systems almost always ensure environmental degradation and long-term losses in different ways. Dubbing these systems “brute force technologies,” Josephson studies how they were employed by varied combinations of diverse political systems, social groups, and economic goals on different types of raw materials in several countries. All led to similarly disastrous results for the ecosystems in question, but, the author argues, man’s hubris is strong enough to convince political and scientific spheres that further innovation can solve problems and maintain profitable advances in the future. While describing the ecological damage caused by brute force technologies, Josephson makes sure to include social stresses inflicted upon local communities, such as native tribes and other underrepresented groups directly affected by the overwhelmingly negative changes.