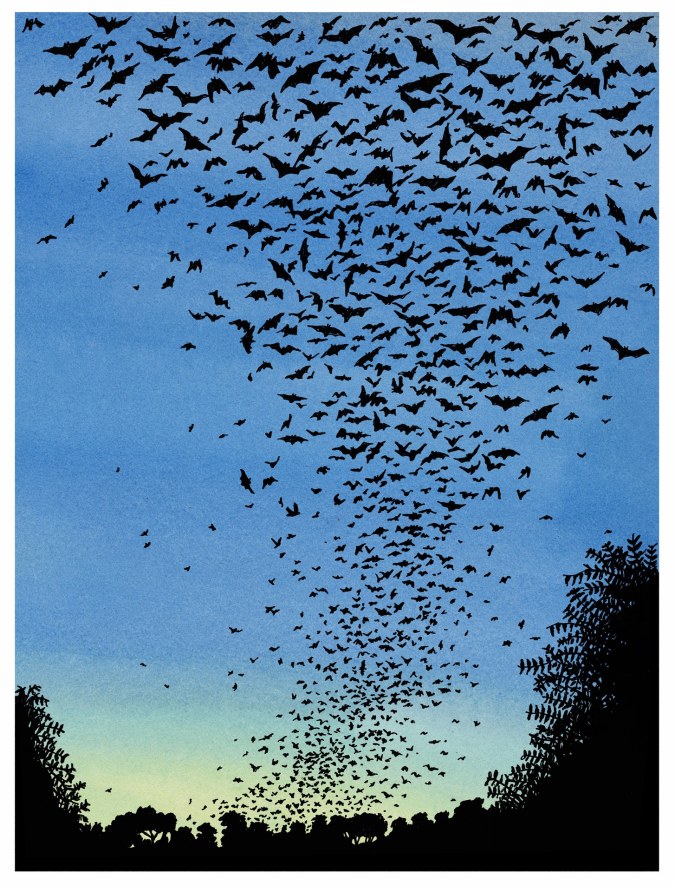

Bracken Cave, a collapsed sinkhole on the side of a lush limestone hill in southern Texas, is home not only to the world’s largest known bat colony but also to one of the largest concentrations of any mammal. More than fifteen million Mexican free-tailed bats live, for part of the year, deep in its recesses. One evening in late July, I visited the cave, situated just outside San Antonio, with a group of bat-curious tourists. As the sun went down, we watched hundreds of bats emerge every second, fifty yards from where we sat, swirling up in what our guide, Niki Lake, a volunteer from Bat Conservation International, called “a batnado.” They created their own breeze, with its own murmur—an ASMR-inducing summer buzz, insectivorous and thrumming, the sound of thousands of beating wings coming in waves. (Lake called the sound a “bat ocean.”) The show would go on for about four and a half hours, until every last bat that could fly had exited the cave. One member of our party said that, if he had discovered this place in prehistoric times, he would have thought it was a portal to another world. As he spoke, I felt a wet spot on my hand. A bat had peed on me.

The bats are so numerous that they appear on radar systems—great blobs popping up and hovering above Bracken Cave every night. (Traffic controllers at San Antonio International Airport have to direct planes to avoid them.) A study published last year used weather-radar records from south-central Texas to analyze the bats’ migration patterns in the course of more than two decades. “Using radar, we were able to see the bats emerging from Bracken Cave every single night for the past twenty-three years,” Charlotte Wainwright, an atmospheric scientist at Notre Dame, told me. Wainwright and Phil Stepanian, the study’s lead author, found that the bats’ spring migration to Texas—they spend their winters scattered across Mexico—had advanced by two weeks. A small percentage of the bats were not leaving Bracken Cave at all. When researchers first visited, in the late nineteen-fifties, there were no bats present in December and January, and yet, according to the data, there are now fifty thousand or more bats emerging during the winter. In the most extreme cases in recent years, more than a quarter of a million bats are spending at least part of the winter at the cave, Stepanian said. “That’s a very sudden change—to have no animals there, to having some, to having so many.”

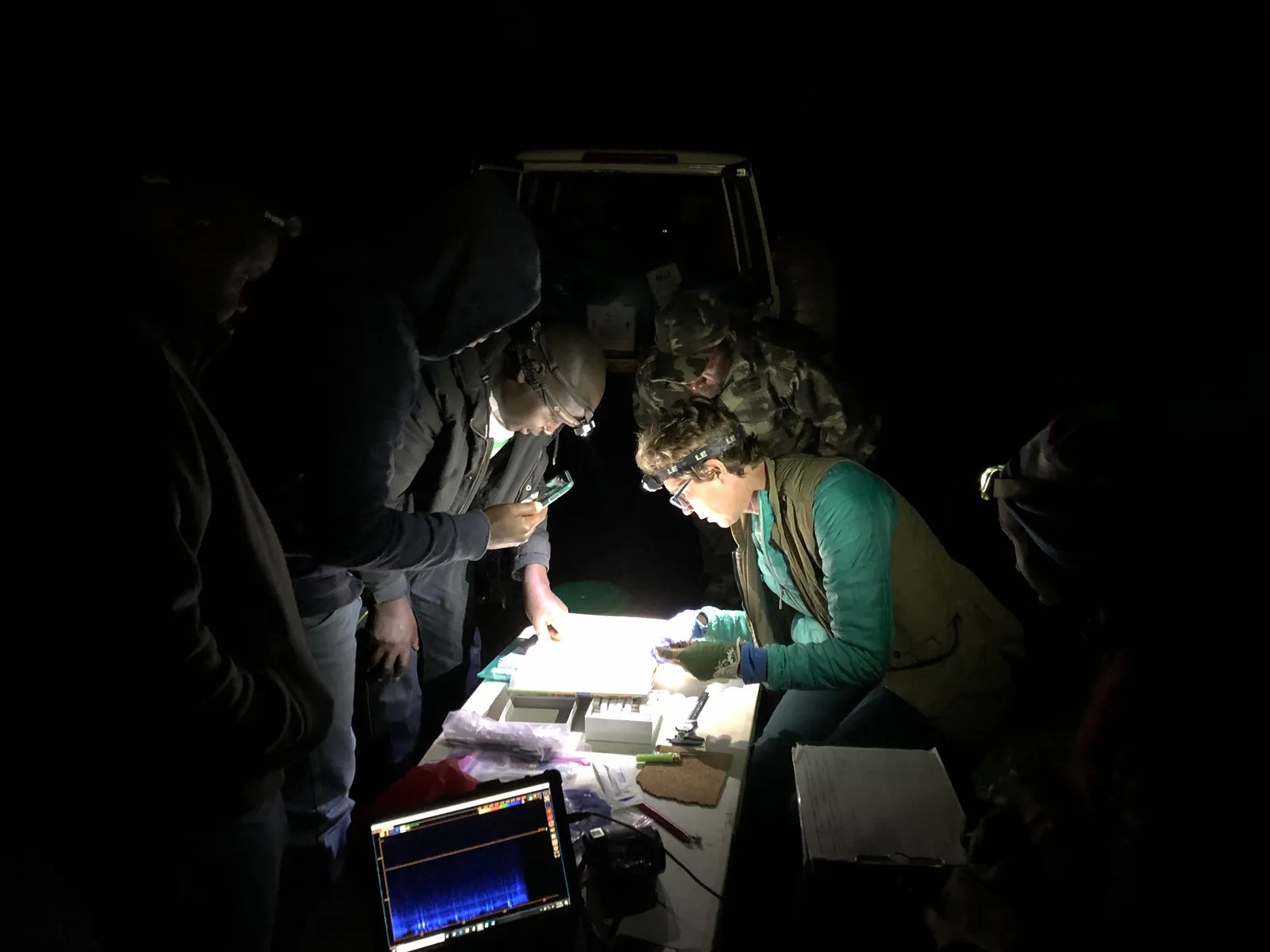

Bats need protection; these clever engineers and scientists will surely figure out how to, considering what they have already accomplished:

Bats need protection; these clever engineers and scientists will surely figure out how to, considering what they have already accomplished:

While in Cockpit Country for our first expedition to Jamaica looking for the Golden Swallow, John, Justin and I watched in awe as hundreds and hundreds of bats flowed out of a cave and flew in a distinct path right by us over the course of half an hour. The slightly shoddy video below can only partly convey the sensation of having the flapping mammals zoom past in a steady stream. We’ve recently featured a couple stories of scientific developments in bat research on the blog, including

While in Cockpit Country for our first expedition to Jamaica looking for the Golden Swallow, John, Justin and I watched in awe as hundreds and hundreds of bats flowed out of a cave and flew in a distinct path right by us over the course of half an hour. The slightly shoddy video below can only partly convey the sensation of having the flapping mammals zoom past in a steady stream. We’ve recently featured a couple stories of scientific developments in bat research on the blog, including