Among the ocean’s best filter feeders, one oyster cleans 50 gallons of water per day. Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

We have linked to stories about the environmental services that oysters provide, as well as the environmental activists who leverage those services; today a riff on those topics:

They Knew Little About Oysters. Now They Have a Farm With 2 Million.

Stefanie Bassett and Elizabeth Peeples left their city lives behind to raise mollusks.

The Little Ram Oyster Co., a farm of 2 million oysters on the North Fork of Long Island, started with a Groupon.

To celebrate a friend’s birthday in the summer of 2017, Stefanie Bassett and Elizabeth Peeples joined eight other enthusiasts in Long Island City to learn how to shuck oysters at a discount. The Brooklyn couple, who knew each other from middle school in Columbia, Md., always had a love for the delicacy. But as they laughed with their friends and fumbled with their oyster knives, they also listened intently as an instructor explained the history and magic of the mollusks.

Ms. Bassett and Ms. Peeples prepare oyster cages to be put into the water. Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

“The thing that drew our attention was the positive environmental impact oysters have,” said Ms. Bassett, 42.

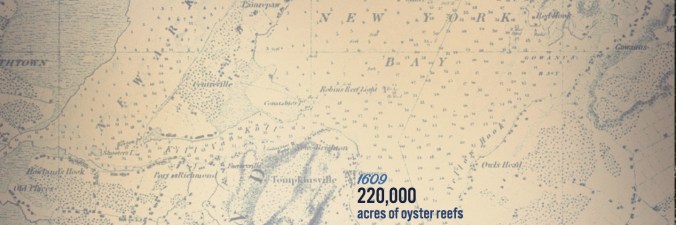

Among the ocean’s best filter feeders, one oyster cleans 50 gallons of water per day. New York was once known as “the Big Oyster,” but over-harvesting and poor water quality wiped out the population by the 21st century. The couple learned about efforts to bring them back to the harbor. Continue reading