In Africa, there are two kinds of elephants: savanna and forest elephants. The species diverged somewhere between two and six million years ago, with the better-known savanna elephants spreading over the plains and open woodlands of Eastern, Southern, and Western Africa while forest elephants stayed behind in the dense forests at the center of the continent. Although the two occasionally hybridize, they are widely viewed as separate species. Forest elephants are smaller, with smaller and straighter tusks. The size of their tusks, however, has not protected them from rampant poaching, because the tusks have a distinctive hue, sometimes known as “pink ivory,” that has made them particularly valuable.

In Africa, there are two kinds of elephants: savanna and forest elephants. The species diverged somewhere between two and six million years ago, with the better-known savanna elephants spreading over the plains and open woodlands of Eastern, Southern, and Western Africa while forest elephants stayed behind in the dense forests at the center of the continent. Although the two occasionally hybridize, they are widely viewed as separate species. Forest elephants are smaller, with smaller and straighter tusks. The size of their tusks, however, has not protected them from rampant poaching, because the tusks have a distinctive hue, sometimes known as “pink ivory,” that has made them particularly valuable.

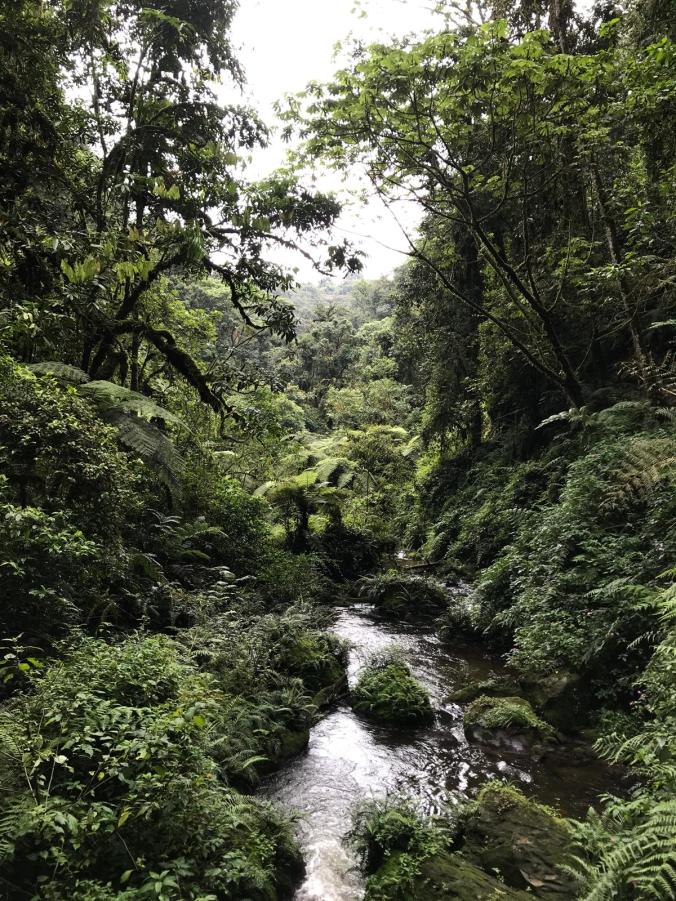

Something about the nobility of forest elephants regularly raises concern for their extinction. The tropical forests of the Congo Basin, once considered impenetrable, are now yielding to logging roads, mines, and even palm-oil plantations. In 2013, a widely respected study by Fiona Maisels, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, found that, between 2002 and 2011, the population of forest elephants had declined by sixty-two per cent. Perhaps as few as eighty thousand remain. The story of these declining numbers is also a story of habitat destruction. Where forest elephants exist in an undisturbed state, they build networks of trails through the deep forest. These trails connect mineral deposits, fruit groves, and other essentials of forest-elephant life. In Central Africa, there are dozens of fruit trees whose seeds are too large to pass through the guts of any other animal and for which forest elephants have evolved as the sole dispersers. These trees line the forest-elephant paths. Where elephant populations are disturbed, the paths disappear.

Something about the nobility of forest elephants regularly raises concern for their extinction. The tropical forests of the Congo Basin, once considered impenetrable, are now yielding to logging roads, mines, and even palm-oil plantations. In 2013, a widely respected study by Fiona Maisels, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, found that, between 2002 and 2011, the population of forest elephants had declined by sixty-two per cent. Perhaps as few as eighty thousand remain. The story of these declining numbers is also a story of habitat destruction. Where forest elephants exist in an undisturbed state, they build networks of trails through the deep forest. These trails connect mineral deposits, fruit groves, and other essentials of forest-elephant life. In Central Africa, there are dozens of fruit trees whose seeds are too large to pass through the guts of any other animal and for which forest elephants have evolved as the sole dispersers. These trees line the forest-elephant paths. Where elephant populations are disturbed, the paths disappear.

Matt Davis, a researcher in ecoinformatics and biodiversity at Aarhus University, in Denmark, recently published a paper arguing that we are entering a period of extinction of large mammals akin to the scale of the extinction of the dinosaurs. “We are now living in a world without giants,” he told the Guardian, and went on to detail the many ecological consequences of the loss of megafauna. When I asked John Poulsen, an assistant professor of tropical ecology at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, if this observation could apply to the role of forest elephants, he said, “Absolutely.”

Matt Davis, a researcher in ecoinformatics and biodiversity at Aarhus University, in Denmark, recently published a paper arguing that we are entering a period of extinction of large mammals akin to the scale of the extinction of the dinosaurs. “We are now living in a world without giants,” he told the Guardian, and went on to detail the many ecological consequences of the loss of megafauna. When I asked John Poulsen, an assistant professor of tropical ecology at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, if this observation could apply to the role of forest elephants, he said, “Absolutely.”

The sculptor Todd McGrain has made a name for himself, over a thirty-year career, as the creator of sculptural monuments to birds that have been the victims of “human-caused extinction.” It’s not, therefore, entirely surprising that he has directed a documentary about forest elephants, “Elephant Path / Njaia Njoku,” showing at New York’s DOC NYC film festival this Wednesday and Thursday. McGrain’s subjects have included, among others, the passenger pigeon, the great auk, the Labrador duck, the heath hen, and the Carolina parakeet. When McGrain was the artist in residence at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Katy Payne, founder of the Elephant Listening Project at the Bioacoustics Research Program, introduced him to something she had discovered: forest-elephant infrasound, which is how elephants communicate inside the forest, at a frequency too low for human ears to register. She pitched up the recordings of elephant calls so that McGrain could listen to them. “I couldn’t help but hear them as bird calls,” he told me. “It was the complexity of their language that grabbed me.” Continue reading →