Dr. Odile Madden, of the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, holding a piece of degrading plastic for use in trying out new methods of preservation. Credit Melissa Lyttle for The New York Times

The irony of the need to conserve aging national treasures or works of art configured from plastics and other petroleum-based materials in the time of the “Pacific Vortex” and other plastic-created environmental disasters is difficult to miss. It never would have occurred to any of us that a field called “Plastics Conservation Science” has any need to exist.

And yet, it does…

These Cultural Treasures Are Made of Plastic. Now They’re Falling Apart.

Museum conservators are racing to figure out how to preserve modern artworks and historical objects that are disintegrating.

The custodians of Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit at the National Air and Space Museum saw it coming. A marvel of human engineering, the suit is made of 21 layers of various plastics: nylon, neoprene, Mylar, Dacron, Kapton and Teflon.

The rubbery neoprene layer would pose the biggest problem. Although invisible, buried deep between the other layers, the suit’s caretakers knew the neoprene would harden and become brittle with age, eventually making the suit stiff as a board. In January 2006, the Armstrong suit, a national treasure, was taken off display and stored to slow the degradation.

Of an estimated 8,300 million metric tons of plastic produced to date, roughly 60 percent is floating in the oceans or stuffed in landfills. Most of us want that plastic to disappear. But in museums, where objects are meant to last forever, plastics are failing the test of time.

“It breaks your heart,” said Malcolm Collum, chief conservator at the museum. The Armstrong suit’s deterioration was arrested in time. But in other spacesuits that are pieces of astronautical history, the neoprene became so brittle that it shattered into little pieces inside the layers, their rattling a brutal reminder of material failure.

Art is not spared either, as Georgina Rayner, a conservation scientist at Harvard Art Museums, showed at the American Chemical Society’s national meeting in Boston this month.

Claes Oldenburg’s “False Food Selection,” a wooden box containing plastic models of foods like eggs and bacon, a banana and an oatmeal cookie, now appears to be rotting. The egg whites are yellowing, while the banana has completely deflated.

In museums, the problem is becoming more apparent, Dr. Rayner said in an interview: “Plastics are reaching the end of their lifetimes kind of now.”

Of all materials, plastics are proving to be one of the most challenging for conservators. “I find plastics very frustrating,” said Mr. Collum. Because of the material’s unpredictability and the huge variation in forms of deterioration, he said, “it’s just a completely different world.”

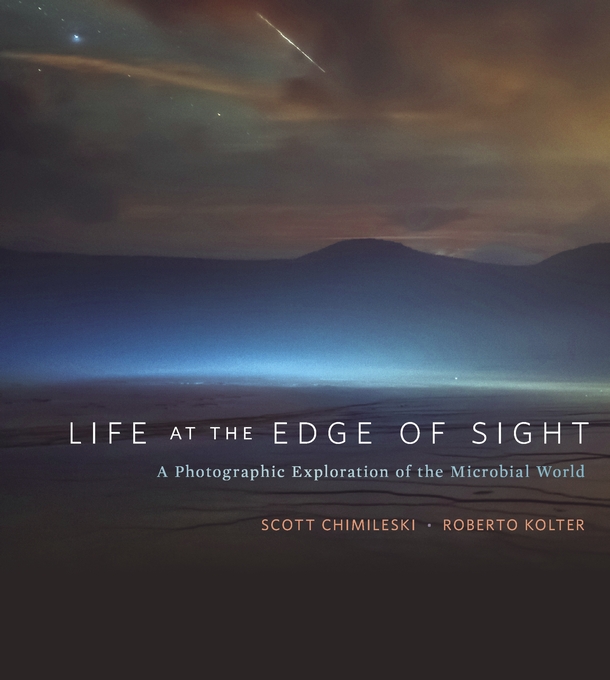

IN ROCKS AND SOIL

IN ROCKS AND SOIL on Earth. Life at the Edge of Sight: A Photographic Exploration of the Microbial World (forthcoming from The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), brings the planet-shaping diversity of these single-celled, microscopic organisms into view through stunning images. Co-authors Roberto Kolter, professor of microbiology and immunology, and Scott Chimileski, a research fellow in microbiology and immunology at Harvard Medical School, share their passion for the subject in part by magnifying what cannot be seen unaided, in part by revealing large-scale microbial impacts on the landscape. Kolter has long been a leader in microbial science at Harvard, while Chimileski brings to his scholarship a talent for landscape, macro, and technical photography…

on Earth. Life at the Edge of Sight: A Photographic Exploration of the Microbial World (forthcoming from The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), brings the planet-shaping diversity of these single-celled, microscopic organisms into view through stunning images. Co-authors Roberto Kolter, professor of microbiology and immunology, and Scott Chimileski, a research fellow in microbiology and immunology at Harvard Medical School, share their passion for the subject in part by magnifying what cannot be seen unaided, in part by revealing large-scale microbial impacts on the landscape. Kolter has long been a leader in microbial science at Harvard, while Chimileski brings to his scholarship a talent for landscape, macro, and technical photography…

technologies. With expertly executed photography, videography, and poetic narration, Scott Chimileski and Roberto Kolter capture the intrinsic beauty of a mysterious world that is seldom recognized.

technologies. With expertly executed photography, videography, and poetic narration, Scott Chimileski and Roberto Kolter capture the intrinsic beauty of a mysterious world that is seldom recognized.