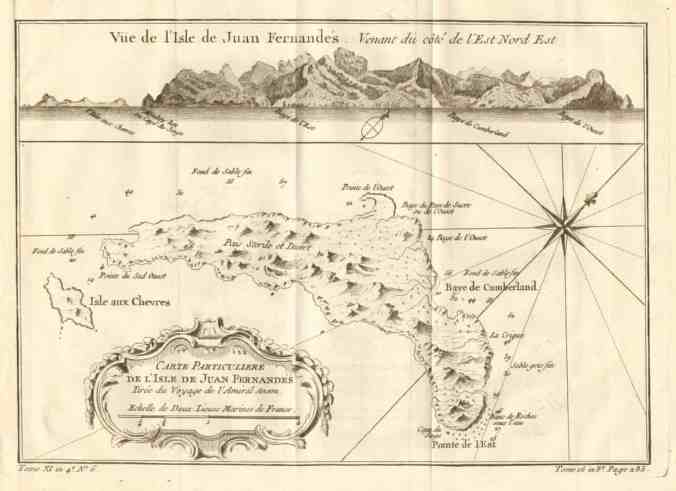

The Millennium Atoll in Kiribati, the Pacific state that is sponsoring Michael Lodge for re-election as ISA leader. Photograph: Mauricio Handler/Getty

Before we leave the subject of oceans, back to the question of how their protection is managed, and by whom.

We are learning today that some of the planet’s smaller nation states have a potentially significant, and clearly long overdue influence on how the oceans surrounding them will be protected:

The rare dumbo octopus (Cirrothauma murrayi) is one of many creatures potentially at risk from deep-sea mining. Photograph: NOAA

Inside the battle for top job that will decide the future of deep-sea mining

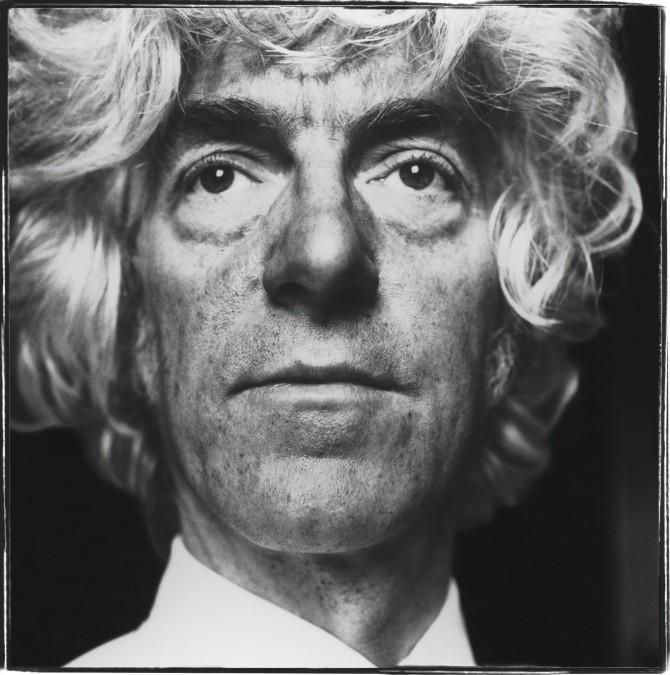

Marking a pivotal moment for the fate of the barely known ecosystems on the ocean floor, 168 nations will decide this week who will head the International Seabed Authority

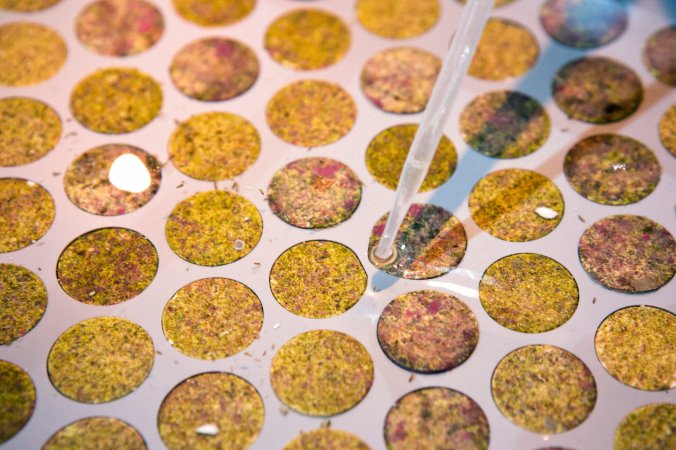

Deep-sea mining exploration trials under way in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico. Photograph: Richard Baron/The Metals Company

Leticia Carvalho is clear what the problem is with the body she hopes to be elected to run: “Trust is broken and leadership is missing.” Later this week, at the headquarters of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Kingston, Jamaica, nations negotiating rules governing deep-sea mining face a critical vote that could impact the nascent industry for years: who should be the next leader of the regulatory body? Continue reading