Conservation-minded scholars hope to harness the cultural power of animal prints. Illustration by Na Kim

It is difficult to judge from Rebecca Mead’s article Should Leopards Be Paid for Their Spots whether and how the idea has a practical future, although the exemplary collaboration between Panthera and Hermes has allure. The concept has plenty of merit, from my vantage point 26 years into an entrepreneurial career that shares some common ground.

If travelers are willing to pay a premium to support the conservation of a place; if they buy things to take home because those things support artisans and farmers; and continue to buy the coffee when back home because it funds bird habitat regeneration (customers tell me via email that in addition to the coffee being excellent, this is a motivator), then why not this too:

When Jacqueline Kennedy was living in the White House, in the early sixties, she relied upon the taste of Oleg Cassini, the costume designer turned couturier, to supply her with a wardrobe that would befit her role as First Lady, one of the most photographed women in the world. In 1962, Cassini provided her with a striking leopard coat. Knee-length, with three-quarter sleeves and six buttons that fastened across the chest, the coat was not made from a synthetic leopard-patterned fabric. Continue reading

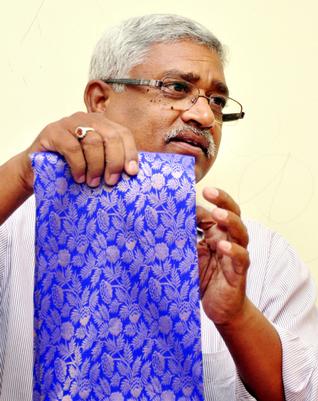

A sari: five yards of unstitched fabric ingeniously wrapped and draped. Nowadays, with the exhausting rhythm of fashion, tons of unwanted secondhand saris are discarded every day and collected by India’s informal rag-picker community who resell these fabrics. This task has gotten harder and harder to do as India’s GDP per capita rises along with a distaste for secondhand.

A sari: five yards of unstitched fabric ingeniously wrapped and draped. Nowadays, with the exhausting rhythm of fashion, tons of unwanted secondhand saris are discarded every day and collected by India’s informal rag-picker community who resell these fabrics. This task has gotten harder and harder to do as India’s GDP per capita rises along with a distaste for secondhand.