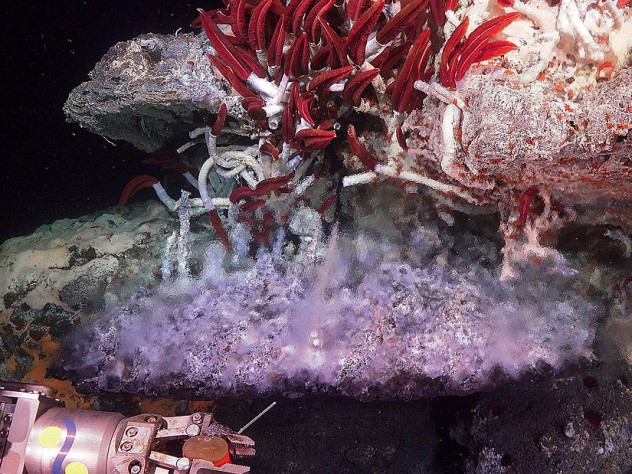

The Indian Purple Frog, first described by Sathyabhama Das Biju in 2003.

Who will fight for the frogs?

Indian herpetologists bring their life’s work to Harvard just as study shows a world increasingly hostile to the fate of amphibians

Having pulled themselves from the water 360 million years ago, amphibians are our ancient forebears, the first vertebrates to inhabit land.

After 136 years from its original description, Günther’s shrub frog was recently rediscovered in the wild. Credit: S.D. Biju and Sonali Garg

Now, this diverse group of animals faces existential threats from climate change, habitat destruction, and disease. Two Harvard-affiliated scientists from India are drawing on decades of study — and an enduring love for the natural world — to sound a call to action to protect amphibians, and in particular, frogs.

Sathyabhama Das Biju, the Hrdy Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute and a professor at the University of Delhi, and his former student Sonali Garg, now a biodiversity postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, are co-authors of a sobering new study in Nature, featured on the journal’s print cover, that assesses the global status of amphibians. It is a follow-up to a 2004 study about amphibian declines.

Franky’s narrow-mouthed frog is among the threatened species. Credit: S.D. Biju and Sonali Garg

Biju and Garg are experts in frog biology who specialize in the discovery and description of new species. Through laborious fieldwork, they have documented more than 100 new frog species across India, Sri Lanka, and other parts of the subcontinent.

According to the Nature study, which evaluated more than 8,000 amphibian species worldwide, two out of every five amphibians are now threatened with extinction. Climate change is one of the main drivers. Continue reading →