View of the Klamath from Orleans, California, ancestral Karuk territory. For millennia, the Yurok, Karuk and Hupa of northern California, and indigenous tribes worldwide, passed the use of fire down through generations as a means of land stewardship and survival. Light, frequent burning created fire-adapted landscapes.

I recall during the pandemic reading the work of Ferris Jabr, which expanded on our understanding of the social networking of trees, an idea I remain compelled by. Now he has a book, adapted for The Atlantic. In the essay form he focuses on the value of indigenous knowhow handed down generation to generation for centuries. He highlights how fire is a wild, powerful element of nature, wielded as a tool for stable life of ecosystem and society.

I recall during the pandemic reading the work of Ferris Jabr, which expanded on our understanding of the social networking of trees, an idea I remain compelled by. Now he has a book, adapted for The Atlantic. In the essay form he focuses on the value of indigenous knowhow handed down generation to generation for centuries. He highlights how fire is a wild, powerful element of nature, wielded as a tool for stable life of ecosystem and society.

Detail of a landscape during a cultural prescribed burn training (TREX) hosted by the Cultural Fire Management Council and the Nature Conservancy in Weitchpec, California. (Alexandra Hootnick)

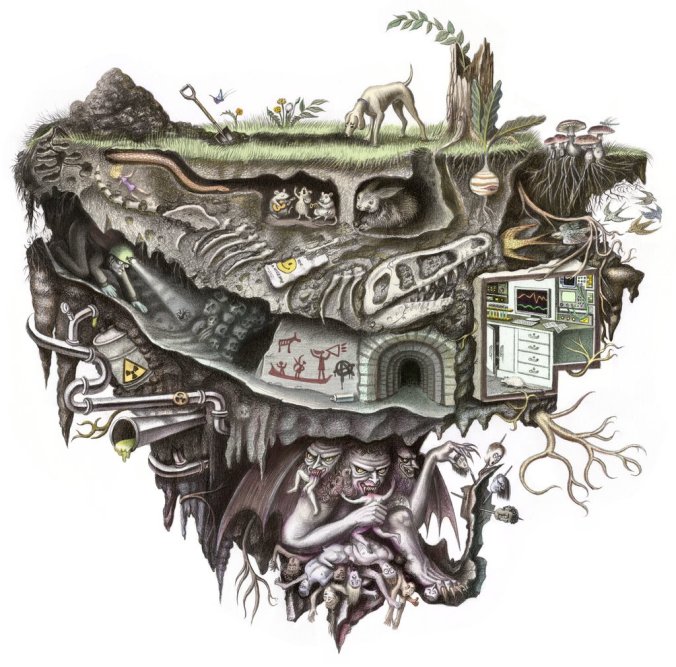

THE DEEP CONNECTION BETWEEN LIFE AND FIRE

How wildfire defines the world

Perched on a densely forested hill crisscrossed with narrow, winding, often unsigned roads, Frank Lake’s house in Orleans, California, is not easy to find. On my way there one afternoon in late October, I got lost and inadvertently trespassed on two of his neighbors’ properties before I found the right place. When Lake, a research ecologist for the United States Forest Service, and his wife, Luna, bought their home in 2008, it was essentially a small cabin with a few amenities. They expanded it into a long and handsome red house with a gabled entrance and a wooden porch. A maze of Douglas firs, maples, and oaks, undergrown with ferns, blackberries, and manzanitas, covers much of the surrounding area. Continue reading